Chronicling lives more than religion

Midway through a tour last week of the National Museum of American Jewish History, deputy curator Josh Perelman paused.

Midway through a tour last week of the National Museum of American Jewish History, deputy curator Josh Perelman paused.

"Does the word 'God' appear anywhere in the museum?' " he mused, repeating the question just posed to him. "Hmmm," he said, and stroked his chin.

"Well, it certainly appears in some of the documents on display. But does it appear in the exhibition texts?" Glancing across the museum's atrium to its four exhibit floors, he mentally scanned the collection.

Down there, in a case, sat the piano of songwriter Irving Berlin. Over there was a monitor showing scenes from Seinfeld, and a metal bunk from a Jewish summer camp. Up there was the Civil War uniform of a Jewish soldier, an exhibit on the 1951 Rosenberg spy trial, and a 19th-century Maryland law giving legal protection to Jews.

But God?

"Hmmm," Perelman said again. With a small shake of his head, he resumed the tour.

The deity known as Adonai, Shaddai, Avinu, Elyon, and Elohim never shows his face at the Jewish museum, which celebrates its new home this weekend and opens to the public Nov. 26. Likewise, there are no exhibits that explain the religious tenets of Judaism or its theology.

And yet the faith and practice of Judaism are everywhere in the 25,000 square feet of gallery space devoted to the Jewish experience in America.

"For us to try to explain Judaism as a set of beliefs and practices, in all its shapes and forms - that was a challenge beyond us," Perelman later explained. "Our space is limited.

"What we've tried to do instead is illustrate to our visitors the lived experience of being a Jew throughout American history," he said. "We're hoping they walk away with a sense of what it has meant to be a Jew in this country."

After entering on Market Street, visitors are invited to start their tour on the fourth floor, in the year 1654, and descend through time, floor by floor, to the present, inspecting more than a thousand artifacts along the way.

A great majority of the items are secular - immigration documents from Ellis Island, a sewing machine, the upright piano at which the Russian-born, agnostic, but ethnically Jewish Berlin penned such tunes as "White Christmas," "Easter Parade," and "God Bless America."

But here, too, are examples of the Torah scrolls, bibles, prayer books, menus, candlesticks, kiddush cups, bat mitzvah dresses, and yarmulkes that have helped sustain Judaism in America for three and a half centuries.

"I think we did a pretty good job," said Perelman.

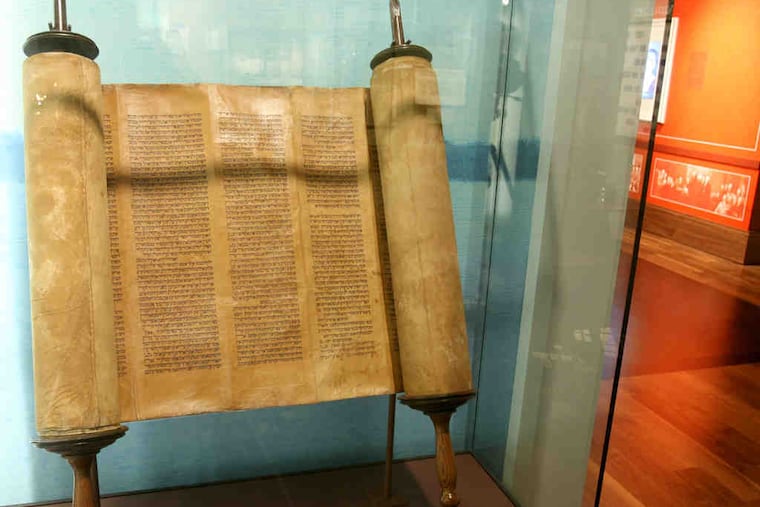

The tour begins with artifacts of Jewish life in the colonies. Here, behind glass, is a 1737 Torah from Savannah, Georgia; a plain, bronze menorah, or liturgical candelabrum; a circumcision kit; the wooden top of a Torah ark from Lancaster County; the bible of the Gomez family - New York mill owners who had fled the Spanish Inquisition; and the handwritten "subscription list" of donors who, in 1728, created America's first synagogue, Shearith Israel, in New York City.

"And here's something I love," said Perelman, wiping the fingerprints from a glass case that had already attracted much attention.

"This," he said, pointing to the page within, "is the 'Richmond Prayer,' " composed in Hebrew by a Virginia congregation in 1789 in honor of the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

"It's a prayer for our country," he said, gazing fondly at its uneven, hand-lettered lines resembling verse. The first Hebrew letter on the right of each line creates a vertical anagram spelling out the name "George Washington."

"It's really one of a kind," said Perelman. The prayer is part of the museum's permanent collection; about 45 percent of the items on display are on loan.

The next room, called "Building Traditions," visits American Judaism from the early 19th century to the Civil War. Again there are examples of the traditional Judaica from the period: leather tefillin, or prayer boxes; a long, hand-knit circumcision robe; a shofar, the ram's horn used to announce the high holidays; samples of ketubot, Jewish marriage documents; and the 1862 commission of Rabbi Jacob Frankel of Philadelphia, the first Jewish military chaplain. It is signed by Abraham Lincoln.

But, here, too, are the first signs of division in American Jewry's understanding of what it means to be religiously observant.

The displays tell the story of Congregation Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in Charleston, S.C., where, in 1824, 47 members signed a petition demanding sermons and some prayers in English, shorter services, and an end to special deference to the wealthy and social elites.

When the leadership refused, the 47 broke away to start the Reformed Society of Israelites, precursor to the Reform movement that would become the nation's largest Jewish denomination.

The display features the community's ornate silver tzedekah (charity) box, along with the manuscript edition of its radically "reformed" prayer book in English and Hebrew.

An adjacent gallery tells the story of the deepening divisions within Jewry as some challenged traditions thousands of years old.

In 1853, Philadelphia's Rabbi Isaac Leeser had published the first English translation of the Bible - a copy of which is displayed - but a decade later the controversial "Leeser Bible" seemed tame.

Should Jews worship on Sundays, some rabbis wondered? Was the Talmud "obsolete," asked Rabbi David Einhorn, an early leader of Philadelphia's Congregation Keneseth Israel? He also installed the first pipe organ in an American synagogue.

The exhibit also features an original menu from the famous - or notorious - "Trefa Banquet" of July 11, 1883, at which the founders of Cincinnati's new Reform seminary served their 215 guests a gala dinner of crab, shrimp, oysters, clams, and meat dishes served with milk, all of which are tref, or nonkosher.

Although no pork was served at the nine-course meal, it "underscored the sharp divisions within American Judaism," notes the exhibit, which includes a silver oyster fork - unimaginable to Jews of Europe or Palestine - belonging to the event's Jewish caterer.

"I don't like the word 'Americanization,' " said Perelman, a scholar of Jewish and American studies who joined the museum five years ago, when it was still a tiny exhibition space a few blocks away, at 44 N. 4th Street. "But we're seeing here the process by which Jews were melding their traditions to the mores of their American homeland - a process that did not happen neatly or easily."

It is a process that developed ever more rapidly with the 19th century's great age of mass immigration, a story told on the third floor.

Artifacts here include religious items typical of those that the hundreds of thousands of Jewish emigres brought with them: Hanukkah oil lamps, brass candlesticks, and gaily colored Rosh Hashanah cards.

Here, too, is a replica of a typical tenement kitchen, where young visitors are invited to sit at a plain table and handle the imitation silver shabbat candles and wine cup, then lift an embroidered cloth revealing two plastic loaves of challah bread.

"On Friday evenings, Jewish families welcome shabbat, the Jewish day of rest, by lighting candles . . . ," the text on the wall explains.

The second floor focuses on Judaism since World War II, including the spread of Jews to suburbia. Here the solemnity and nostalgia of the previous floors give way to a Judaism more contemporary, familiar, and lighthearted.

The walls feature photos of 13-year-old boys smoking cigarettes at a bar mitzvah party; a teenage girl of the 1960s dancing the frug after her bat mitzvah; scenes of Jewish summer camps; a plastic, plug-in Hanukkah menorah; and a large photo and video gallery that displays the bold designs of postwar suburban synagogues by some of America's premier architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright's Beth Sholom in Elkins Park.

"Jews are not only saying 'We're here,' " noted Perelman, "but in a decidedly American way."

A display case on contemporary Judaism alludes to its postmodern diversity. Alongside a Hasidic man's hat and woman's wig sits the text for a lesbian seder and a photo of Elysse Stanton, the nation's first African American female rabbi.

"It's a long way from the Gomez bible" and other colonial-era Judaica on the fourth floor, Perelman said.

"We could have presented our religion in terms of God, theology, and institutions," he said. "Instead we chose to present it as a lived experience."