Art: Images drive, words take a backseat

In "LitGraphic" the art of storytelling is in the pictures. Still, there's much reading to do.

G

raphic novel

is a slippery denomination, almost an oxymoron. Such tales, whether bound as a book or printed in comics format with paper covers, are certainly graphic - being visual is, after all, their defining characteristic. But can they possibly be novels?

With one possible exception, Art Spiegelman's Maus, I think not. Graphic narratives would seem to be a more apt characterization. Certainly no examples offered by the exhibition "LitGraphic" at the James A. Michener Art Museum approach the textual complexity and character development of a traditional novel.

One must acknowledge, however, that over the last several decades the graphic novel has become a familiar genre. A typical specimen tells its story through a combination of words and pictures, like a comic book.

The difference between the pop-culture progenitor and the evolved graphic narrative is that the latter has literary pretensions that, as we see in this exhibition, are occasionally realized.

The show was developed at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass., which suggests that we're supposed to regard the graphic narrative as a collateral relative of illustration. Yet it's not quite illustration as Rockwell practiced it because he didn't tell stories so much as distill common emotions and life experiences.

Graphic narratives use drawings not to enhance a story told in words but to drive the story itself. Most include text, but text isn't always necessary: Some graphic narratives function perfectly well without it.

The exhibition includes a splendid example of the wordless narrative, 49 small wood engravings by Lynd Ward (1905-85) called God's Man. The sequence describes "an artist's struggle with his craft, his seduction and abuse by society and his escape to innocence."

Aside from a few bound volumes such as Robert Crumb's Yum Yum Book, which visitors can't peruse, God's Man is the most extended sequence in the show proper. (The complete story involves 139 images, so a little more than a third is displayed.)

God's Man is also one of the show's most impressive works, in terms of both literary quality and graphic technique.

Generally, each of the two dozen artists is represented by storyboards that sample drawing style and the tone and thrust of a characteristic narrative. This makes the show a tasting buffet rather than an extended engagement with any single artist.

The format also means that one doesn't receive enough exposure to the genre to decide how effective it can be for storytelling, or in developing any of the other attributes of the novel that might justify use of the term graphic novels. An exhibition of this kind, in an art museum, just doesn't make the strongest argument for the thesis.

That said, it's ironic that a presentation based mainly on drawings - and much of the drawing is virtuosic of its kind - should demand so much reading. One could spend hours in this show reading except for the fact that fatigue would be a deterrent.

(A half-hour video program - five-minute interviews with six of the participating artists - provides some welcome relief from endless speech balloons.)

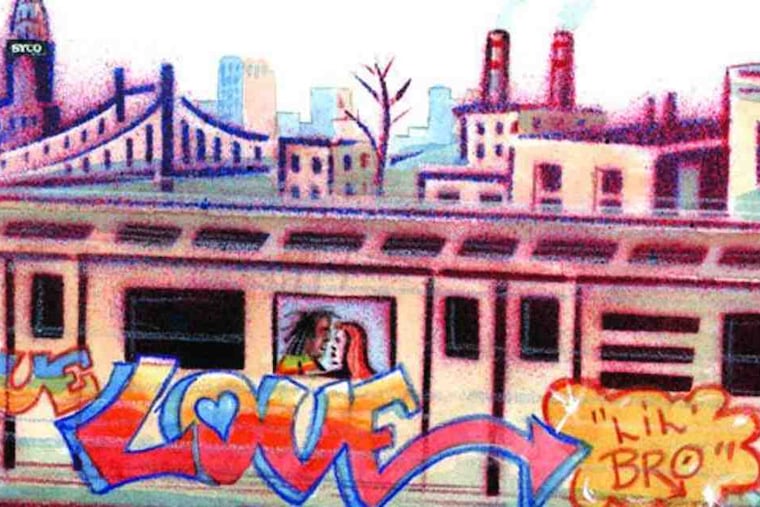

The exhibition format is tantalizing, but ultimately frustrating. You see four drawings by Crumb, one of the celebrated graybeards of this genre, and you want a whole story. The same goes for Will Eisner, whose film-noir style is perfectly suited to the stories of life in a Bronx tenement that he published in 1978 as A Contract With God.

(This R-rated book is among a few that one can go through cover to cover in the video alcove.)

The artist I really missed was Spiegelman, whose two-part Holocaust tale called Maus conferred legitimacy on serious graphic storytelling two decades ago. He was included in the original version of the show, but his drawings were withdrawn from the Michener edition at the last minute.

For me, a show of this kind without Spiegelman is like a collection of 17th-century Dutch paintings without Rembrandt.

The more one looks at other talented comic-style artists such as Sue Coe, Lauren Weinstein, Marc Hempel, and Peter Kuper, the more one realizes that we've been seeing graphic storytelling of this kind for several generations, not only in Classic Comics but from artists such as Maurice Sendak and Edward Gorey (and why aren't they in the show, I wonder?).

So why have graphic novels proliferated in this decade? Could it be because the video and digital generations are not only more comfortable with visual narratives but also because these technologies have shortened attention spans and programmed young minds to dance lightly over texts?

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the graphic narrative might be literature's evolutionary equivalent of texting. When a graphic artist produces the storyboard equivalent of Vanity Fair or War and Peace, then I'll hop on the bandwagon.

Dante rejuvenated, sort of. In her installation at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Joan Jonas, who enjoys an elevated reputation as a video and performance artist, wrestles with the immortal Italian poet Dante Alighieri and his masterpiece, The Divine Comedy.

Fortunately for Western civilization, Dante survives the encounter without a mark on him.

This is because it's difficult to recognize allusions to the allegorical epic in Jonas' Reading Dante III, a 45-minute video installation that involves performances in diverse locations and in which drawing also figures prominently.

Jonas attempts to recast Dante's classic in a multimedia contemporary idiom. This involves continuous scene-shifting, people in costumes wearing animal heads, various astronomical references, and frequent use of mirrors.

I venture that it would take a Dante scholar to make much sense of what, to a novice, comes across as a disjointed mishmash of images and music, without the whisper of a unifying theme.

Jonas will give a live performance of an earlier version, Reading Dante II, at the workshop Saturday at 7 p.m.

Her installation includes two other videos that are more compelling. One, related to Dante, consists of shapes being drawn and erased, in chalk on a blackboard.

The other, which she made in the 1970s with artist Pat Steir, was filmed on a New York street at night. An unidentified man wanders before the camera, providing a slightly surreal bit of improvisation that illuminates the creative potential of chance encounters.

Art: Told With Pictures

EndText