Art: Imprisoned by his most famous painting

As R. Tripp Evans observes in his biography of Grant Wood, American Gothic may be the second-most-parodied painting in history, after the Mona Lisa.

As R. Tripp Evans observes in his biography of Grant Wood, American Gothic may be the second-most-parodied painting in history, after the Mona Lisa.

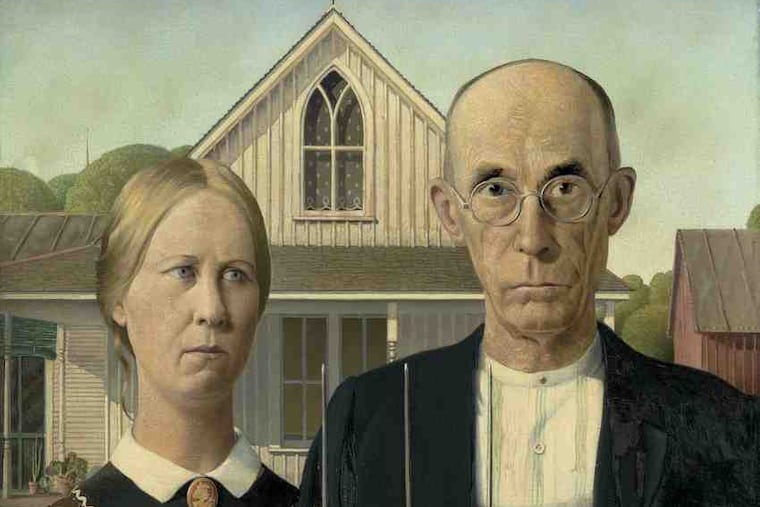

Surely you know the image - a dour, elderly farmer clutching a menacing pitchfork standing next to an anxious-looking woman in front of a small carpenter Gothic house. It's an odd, unsettling portrait of Midwestern archetypes that made Wood famous, yet it eventually imprisoned him in a role as a champion of "regional" art for which he was ill-suited.

He was inspired to create the painting by the house, which he discovered in an Iowa town called Eldon. For the couple he posed his sister, Nan, and his dentist, Byron H. McKeeby.

Apparently he intended that they should reflect, in an affectionate way, the architectural character of the house, which he admired. Yet the resulting image turned out to be something readily perceived as parody.

Perhaps because of its strange ambiguity, the 1930 painting became an American classic. It's mainly how he's remembered today.

In Grant Wood: A Life, Evans, who teaches at Wheaton College in Norton, Mass., dissects American Gothic assiduously, in fascinating and persuasive detail. He demonstrates that, far from making fun of straitlaced Midwestern provincialism, it's a window into Wood's troubled psyche, particularly his memories of a childhood dominated by a stern and distant father.

Wood was born in Iowa in 1891 and grew up on a farm. He was more firmly connected to his mother, who lived with him for much of his career. Yet as Evans reports, his personality was bifurcated in a number of ways; ultimately, he wasn't able to reconcile the contradictions.

Primary among these conflicts was his homosexuality, which he successfully concealed until he died of cancer in early 1942, just short of his 51st birthday.

Far more public was the tug-of-war between his European art training and the bohemian urban life he led in Europe in the 1920s, and his image as a small-town man of the soil who, as a leader of the so-called regionalist movement, celebrated heartland values.

Evans effectively demolishes the mythological portrait of Wood that has been passed along for decades. The artist never farmed as an adult, and doesn't appear to have cared much for that life, whose ethos his father embodied.

Evans doesn't say so directly, but his recounting of Wood's career suggests something I have long suspected, that regionalism was a contrived label of commercial convenience.

In the author's reading, Wood's art is highly symbolic and autobiographical. It doesn't observe rural American life through a lens of nostalgic realism, but rather uses Iowa as a stage on which Wood re-creates his sublimated passions, fears, and childhood memories.

One can see this in American Gothic, which is enigmatic, emotionally frigid, and, as Evans observes, even slightly creepy.

Wood painted a psychologically penetrating portrait of his mother, called Woman With Plants, but he never portrayed his father. American Gothic is as close as he got.

Just as strange, and perhaps more enigmatic, are Wood's landscapes of rolling Iowa farmland. They have always struck me as excessively idealized, more toyland dreams than observed reality.

Evans interprets these surreal scenes, so perfect and orderly, as homoerotic fantasies, with the rounded hills and contours standing in for muscular male anatomy.

One eventually concludes from his absorbing narrative that Wood was a tragic figure. He might have developed into a quite different artist if, after living and studying in Europe during the 1920s, he had settled somewhere more congenial to his temperament.

Instead he returned to Iowa, in part to support his widowed mother, but where the emotional conflicts in his life became magnified rather than clarified.

The female van Gogh. Grant Wood may have become famous for the wrong reasons, but Alice Neel labored in relative obscurity until she was well into her 60s.

Not only was she a woman working in an art world dominated by men, she was also a portrait painter during a time when American art was trying to absorb European modernism.

And although Neel lived in New York, she worked outside the clubby intimacy of the Manhattan art scene in Spanish Harlem, raising two sons, painting her friends and neighbors, the canvases piling up in her tenement.

Neel was a genuine bohemian whose life of hand-to-mouth hardship, tragedy, and eventual triumph rivals that of Vincent van Gogh.

It all spills out in Phoebe Hoban's engrossing new biography, Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty, which throws the tribulations and complexities of Neel's character into high relief. For instance, her tenacious will to establish and maintain creative independence contrasts with her need to be paired up - this despite her proclivity for making poor choices - and her ambivalence toward her responsibilities as a mother.

Neel's story has been told before, most recently when the Philadelphia Museum of Art gave her a show in 2001, but never with the narrative drive and poignancy with which Hoban infuses her account.

Neel was born in Merion Square, now Gladwyne, in 1900 and grew up in Colwyn in Delaware County.

She graduated from the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, now Moore College of Art and Design, in 1925, just a few days after marrying Carlos Enriquez, a Cuban painter she had met at a summer art school in Chester Springs.

The marriage, though never legally dissolved, wouldn't last, but it did produce two daughters. One died in infancy, and the second, Isabetta, was reared in Cuba by paternal aunts after Neel and Enriquez separated when the girl was 2. Neel saw her daughter only a few times before Isabetta committed suicide at age 53.

After she moved to New York, Neel had two sons, Richard and Hartley, by different men. Richard suffered serious eye problems as a child, and Hoban reports that he was psychologically abused by Hartley's father when he and Neel were a couple.

Throughout the book, one is acutely aware of Neel's precarious balancing of career and motherhood, never neglecting her art but usually trying to do right by her sons.

As the exhibitions of her late career reveal, she was a confrontational portraitist whose style was broadly expressionist. It certainly was antithetical to commercial success, because it often involved taboo subjects such as poor people and nude pregnant women.

Neel's sensitive social conscience trumped any impulse to prettify or flatter. Honesty is perhaps her most laudatory quality as an artist. She never pulled punches, as we can see in her notorious nude self-portrait at age 80.

Recognition may have come late to Neel, but it was deserved and, as Hoban relates, she reveled in it. Oddly, the final section of the book, in which Neel collects her tributes, is the least interesting.

Conflict and struggle, which she experienced in abundance, make for more gripping storytelling.

Art: Two Lives in Art

Grant Wood: A Life

By R. Tripp Evans

Alfred A. Knopf, $37.50

Alice Neel: The Art

of Not Sitting Pretty

By Phoebe Hoban.

St. Martin's Press, $35.EndText