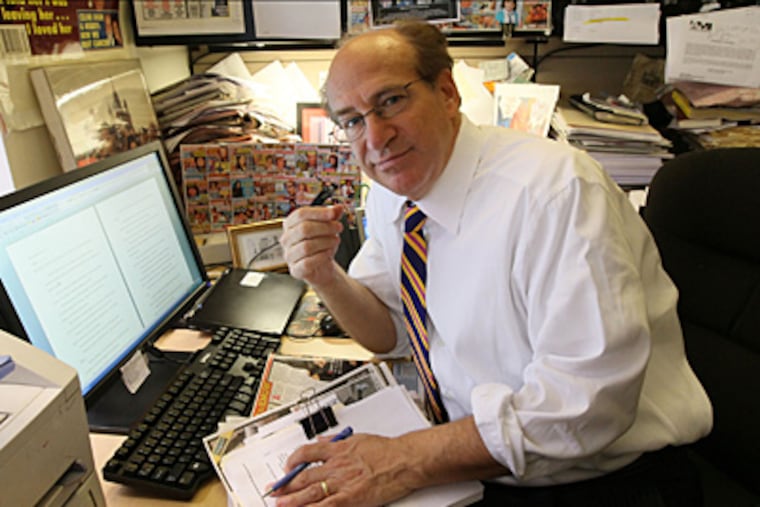

National Enquirer editor Barry Levine helps set the gossip agenda

NEW YORK - When the National Enquirer last week broke the news that Hollywood glam gal Catherine Zeta-Jones had undergone treatment for bipolar disorder, it set off a predictable bleating-and-tweeting frenzy among the media and their gossip-devouring audience. Which meant it was just another day at the office for Barry Levine.

NEW YORK - When the National Enquirer last week broke the news that Hollywood glam gal Catherine Zeta-Jones had undergone treatment for bipolar disorder, it set off a predictable bleating-and-tweeting frenzy among the media and their gossip-devouring audience. Which meant it was just another day at the office for Barry Levine.

As the Manhattan-based executive editor and director of news for the supermarket tabloid, Levine, 52, supervised the reporting and editing of the Zeta-Jones story, just as he had on such landmark scoops as the Tiger Woods and John Edwards scandals.

That the Levittown native has found himself at ground zero of this nation's insatiable appetite for the dirty little secrets of the rich, famous, beautiful and powerful comes as no surprise to those of us who worked with Levine (pronounced Leh-VEEN) at the Temple News in the late 1970s and early '80s. Even then he seemed to be of another era, with his trench-coat-and-fedora wardrobe and penchant for stunt-type stories: In 1976, Levine was inspired by the opening of Dino De Laurentiis' version of "King Kong" to don a gorilla costume and attempt (unsuccessfully, as it turned out) to climb City Hall tower.

"To me the newspaper thing was always about the romanticism of the old Chicago 'Front Page' days," Levine said recently as he sat in his surprisingly small, unkempt midtown office on Park Avenue, soon to be vacated for financial district digs.

"That kind of do-everything mentality, press cards in the hat, running out on stories, exposing things. At the Temple News, we were kind of exposed to that with some of the aggressive reporting we did, not only on campus, but around the city." And beyond, he might have added.

During the summer of '77, Levine spent a couple of weeks in New York working the notorious "Son of Sam" serial-killer case for the paper. "I think that tabloid journalism was really what I had always been seeking in my career," he added. "I was always in love with the romanticism of newspapers and the newspaper life."

'I have the scoop!'

According to Levine, it was the People Paper that, as much as anything, pointed the way for him. "Growing up in Levittown and being a die-hard fan of the Philadelphia Daily News sports page for years - growing up on Bill Conlin and Stan Hochman and some of the other writers they had there through the years - certainly had something to do with me initially wanting to go into sportswriting."

And that's how it started for him: First, as part of his college paper's sports staff (he ultimately served as the Temple News' editor-in-chief), then as a sportswriter in such cities as Detroit and Baltimore. It was in the latter that he realized the tabloid style of newspapering was the way to go.

In the winter of 1984, Baltimore Colts owner Robert Irsay moved the storied and beloved franchise to Indianapolis literally in the dead of night, with no warning to loyal fans. At the time, Levine was a sportswriter for the long-gone Baltimore News American, an afternoon daily owned by the Hearst chain that, he recalled, "had that flavor of old-school reporting."

Getting a tip that something fishy was going on at the Colts' training facility in suburban Owings Mills, Md., Levine drove there in a snowstorm. Stopped at the gate by a security guard under strict orders to keep media people out of the complex, Levine identified himself as a Colts' assistant trainer and was admitted. Once inside, he found then-head coach Frank Kush and asked if the team was leaving town. Kush, citing his admiration for Levine's tenacity in chasing the story, confirmed it.

"I made that call - the only call of my career which all reporters want to make, [when you] call the city desk and literally say, 'Stop the presses! I have the scoop!' " he recalled, his pride evident even with the passage of more than two decades. "That was really the first [tabloid-style] story that I broke."

It also, he admitted, gave him the "taste of blood" that would serve him well in the ensuing years.

Nonetheless, Levine still had some sportswriting dues to pay before he went the supermarket-tabloid route, including a mid-'80s stint as the Eagles beat writer for the Delaware County Times. But his sports-department days ended when someone whose name Levine could not recall sent his clips to the Star, now a corporate sibling of the Enquirer but in the 1980s a top competitor.

Impressed, the Star's editors invited Levine on a two-week tryout that included going to Calgary, Alberta, to confirm rumors that Don ("Miami Vice") Johnson, who was filming a movie there, was romancing Barbra Streisand. Levine headed north of the border but initially crapped out on the story.

"I couldn't get anybody to talk to me," he remembered. "When I got to the airport and went to get my ticket for my trip back to Philly, the guy at the counter said, 'You should have been here just a few minutes ago, Barbra Streisand showed up. The word is she's here to visit Don Johnson.'

"And I thought, 'Holy cow! Forget the ticket!' I ran back, got the photographer. We ended up getting some pictures and were able to be one of the first to report the story. The Star ended up offering me a job."

Much to Levine's surprise - and chagrin - the gig wasn't in New York, but in Hollywood, where the paper planned to ratchet up its show business coverage to compete with the Enquirer.

Although he described his early days in Los Angeles as "a trial by fire," Levine soon became a Star star. He spent the next five years traveling the world in search of celebrity gossip and bad behavior. It wasn't unusual for him to be rousted out of bed by a phone call from an editor ordering him to jump on the next plane to Rio de Janeiro, Moscow (where former heavyweight boxing champ Mike Tyson came very close to tossing him over the side of a hotel stairwell) or any locale where celebrities might be doing something they shouldn't.

His exploits were ultimately noticed by executives at the TV show A Current Affair, a video version of a gossip sheet then hosted by Maury Povich and Maureen O'Boyle and produced by Fox TV - like the Star at the time, a subsidiary of Rupert Murdoch's News Corp. media empire.

Levine joined the program as its managing editor in 1995. While he would garner even greater professional success at his next job, Levine hit the jackpot in his personal life at Current Affair. That's where he met his (second) wife of 13 years, Sharri (rhymes with "starry") Berg, who also worked on the show. The couple have a 6-year-old daughter August, named not for the month but for a 1986 Eric Clapton album.

The seemingly inevitable marriage of Levine and the National Enquirer was consummated in 1999 when he was hired as assistant executive editor and sent to head the newly formed New York bureau. John F. Kennedy Jr. died in a plane crash just weeks after Levine's Enquirer debut, putting him into "Defcon 1" mode for the first of many times. He became executive editor in 2005.

Politicos are celebs, too

Levine recognized early on that thanks to the ever-increasing number of media platforms, some politicians had become another species of rock star. This, he figured, left them open to the same kind of scrutiny the Enquirer and other gossip sheets focused on entertainers.

"That's an area I have branched off into," he said. "We're doing the work that we feel some of the big national papers have failed to do. We've taken our brand of investigative reporting [with which] we've covered celebrities, and turned it on politicians."

In 2001, he scored his first major political scoop breaking the story that the Rev. Jesse Jackson, one-time presidential candidate and Democratic Party power broker, had not only fathered a child out of wedlock but also had set up the mother and daughter in a Los Angeles house paid for by funds from his charity, the Rainbow Coalition.

But that was just the appetizer for the main courses Levine and his minions would later devour. During the past few years, Levine-led reporters have broken the news of extramarital affairs being conducted by golf megastar Tiger Woods and one-time presidential candidate John Edwards.

The Woods scandal was arguably the bigger story (at least if you measure by the amount of jokes made about it by late-night TV hosts), but it was the Edwards saga that changed everything for Levine and his paper.

Last year, the Enquirer received two controversial Pulitzer Prize nominations, including one for Investigative Reporting (the winners in that category were the Philadelphia Daily News' Barbara Laker and Wendy Ruderman for "Tainted Justice," their series exposing police corruption in Philadelphia).

When the nominations were announced, many in journalism complained publicly that the Enquirer's traditional gossip format and its willingness to pay sources precluded it from serious Pulitzer consideration. Maybe so, but that didn't keep the Pulitzer judges from making it a finalist, and the influential Huffington Post website from anointing Levine as one of the 100 "game changers" of 2010.

The Enquirer's stories cost Woods his marriage and untold millions in endorsement deals, while Edwards' toll also included the end of his political ambitions. For the record, Levine, citing the hypocrisy displayed by both men, sleeps fine at night, not at all bothered by his crucial role in their downfall.

He holds Edwards in particular contempt.

"Here was a guy who was not only betraying his cancer-stricken wife, Elizabeth, he was betraying his campaign staff," said Levine. "This is a man who was running for president at the same time he was carrying on an affair with a campaign worker that resulted in her pregnancy. He betrayed his family and he betrayed the American public."

Levine also finds satisfaction in the federal government's current grand jury investigation charged with determining, per the Enquirer's reporting, whether Edwards used campaign funds to try to cover up the affair and birth of his child.

Levine may be a celebrity scourge and a publicist's nightmare. But according to one PR rep who has had to deal with Enquirer revelations about his clients, he conducts himself in an above-board manner with those in his crosshairs.

"While there are times when Barry and I agree, there are many others when we strongly disagree," said Matthew Hiltzik, a New York-based publicist for such news-business figures as CBS News anchor Katie Couric and radio host Don Imus. "But he's always been straightforward and let me know when the truck is about to hit me."

If Levine is wearying of the pace and pressure of a job where he's only as good as his last exclusive, he does an Oscar-caliber job of hiding it. When he talks of scoops past and present, it's with the same enthusiasm and joy seen in the kid who tried to rendezvous with William Penn's statue dressed as an ape.

He positively lit up when the discussion turned to the reported presidential aspirations of real estate mogul Donald Trump, long a favorite Enquirer subject.

"As he said in the interview I did with him a couple of months ago," Levine noted, " 'Thanks to the National Enquirer, I don't have any secrets that can be exposed during the presidential campaign . . . you guys exposed all of them.'

"And he also said, 'Barry, if I do [get elected], the National Enquirer will have the run of the White House.'

"That's what we want to hear!"