Prom book documents change in rite of passage

In high school, he was the guy who shaved his head in solidarity with a buddy who was going through chemo, then let the hair grow back in a mohawk. She was the girl who never wore a dress.

In high school, he was the guy who shaved his head in solidarity with a buddy who was going through chemo, then let the hair grow back in a mohawk.

She was the girl who never wore a dress.

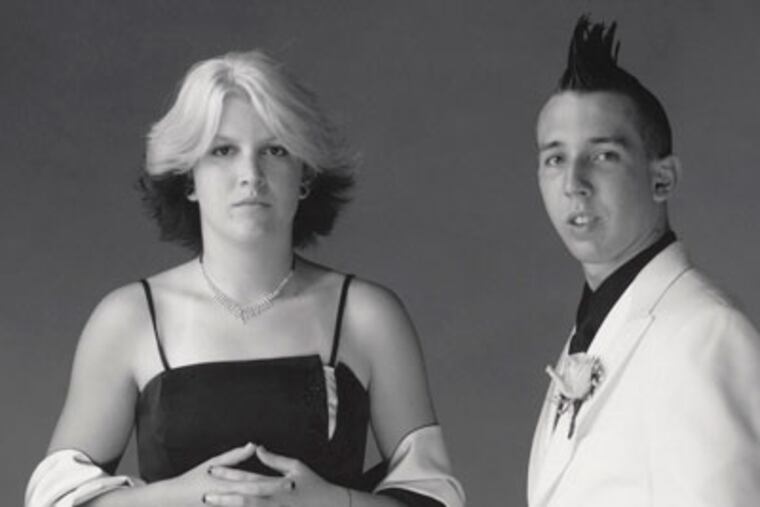

So when Tom Burrows and Meghan Connolly showed up at the 2006 Cheltenham High School prom — he in a white tux and spectator shoes, dark hair in glossy spikes; she in a black spaghetti-strap gown with white accents, fingernails tipped in ebony lacquer — they made a striking pair.

They also caught the eye of photographer Mary Ellen Mark, who included a photo of Burrows and Connolly in her new book, Prom, published in April. The book includes 127 large-format black-and-white photographs of prom-goers from Los Angeles to Staten Island, including a handful from Cheltenham High, Mark's alma mater.

Together, they offer a panorama of how thoroughly proms have changed — there are lesbian couples, a boy in a wheelchair, a girl who is nine months pregnant — and how much the prom remains a unifying ritual, a last hurrah of high school, a one-night bridge between the worlds of teenager and adult.

Mark, known internationally for her photo essays and portraits — some of which hang in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the National Portrait Gallery — said she cherished her own prom picture from 1958 and wondered about today's proms: What would they reveal about teens' social class, aesthetics, and aspirations?

"I'm a photographer of people, a humanist," she said. "For years I've thought of prom as a ritual … a time of your life when you're leaving high school and going on to college or work, and your whole life is ahead of you."

To make the photographs in Prom, Mark used a behemoth 20x24 Polaroid Land Camera, which produces a large-format print with no negative. Only five such cameras are in use throughout the world. Mark rented two of them — one based in San Francisco, one in New York — lugging the contraption to thirteen public, private, and parochial schools in places including Wyncote; Santa Monica, Calif.; Austin, Texas; Newark, N.J.; Ithaca, N.Y.; and Charlottesville, Va.

She sought diversity: At Malcolm X Shabazz High School in Newark, many girls hired local designers to fashion their prom dresses, including one in camouflage fabric with a neckline that plunged deep enough to reveal the wearer's belly-button jewelry.

In Houston, at MacArthur Senior High School, the prom was a fiesta of extravagantly ruffled dresses. "I felt like I was in Oaxaca," Mark said. "They dressed like Mexico, and they all spoke Spanish." At Harvard-Westlake, a private school in Los Angeles, students wore a sense of entitlement along with their designer labels. "The kids had a certain confidence; it's a great advantage to come from wealth," she said. "They were very bright and very secure about their futures."

Mark included several photographs from a New England boarding school for kids with cognitive disabilities and two from the prom held at New York's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center: a trio of girls in evening wear, one's bald head crowned with a tiara, another with an IV line snaking under the hem of her chiffon gown.

Mark was struck by the distance between these proms and her own. From coast to coast, dance floors rocked with first- and second-generation immigrants, kids with unconventional hairstyles and skin-baring gowns that pushed the limits of the dress code. "And the pregnant couple! That was amazing. If you were pregnant in high school [in the 1950s], it was the biggest secret in the world. I thought: Times have really changed."

All the events Mark photographed, except for one, took place in hotels, convention halls, or other luxe spaces, not in a streamer-laced high school gym. Even in lower-income areas, such as Newark, Mark said, extravagance ruled.

A recent survey by Visa Inc. confirmed that hunch; American families with teenagers will spend an average of $1,078 on the prom in 2012, 33.6 percent more than was spent in 2011, and parents in the lowest income brackets plan to spend more than the national average. Limos, expensive formal wear, restaurant dinners, and after-prom festivities have become the norm rather than the exception.

"We have few markers for the transition from adolescence to adulthood, so the prom assumes an odd significance in that regard," says Amy L. Best, a professor of sociology at George Mason University and author of Prom Night: Youth, Schools and Popular Culture. "And at some schools where graduation rates are low, the prom is the defining moment."

The prom, like adolescence itself, embodies the tension between conforming and standing out. For girls in particular, Best says, the prom is an opportunity to emerge as someone different from their everyday persona. "The Friday before prom, girls often wear pajamas or dress down, so when they make a splash at the prom, they're hardly recognizable."

That's exactly what Meghan Connolly wanted. At Cheltenham, "I was the punk-rocky weird girl" who played softball and wanted to become a chef. She tried on half a dozen frilly dresses at David's Bridal until she settled on the crisp, floor-length black-and-white gown. "My dad chuckled when he saw me. My mom was like, 'Oh, my God.'?"

For Burrows, who was a junior at Lower Moreland High School when he attended Connolly's prom, the event was also a metamorphosis: The kid who usually sported T-shirts and ripped jeans cleaned up in dazzling white, with a single snow-colored rose on his lapel.

The two were thrilled to pose for Mark and her giant camera, and happy to talk with her husband, Martin Bell, who interviewed many of the couples and created a 30-minute DVD that is included with the book.

Both Mark and Bell said they were surprised by the students' openness in discussing their relationships, their families, and their futures. "It was touching how optimistic all the kids were," Mark said. "I expected the kids who came from harder families and fewer opportunities to be bitter, and they weren't."

And the couple were especially moved by Ashley Conrad, a patient at Sloan-Kettering, whose bald head was a consequence of chemotherapy. In the film, Conrad talks about the perspective cancer has given her, an ability to shrug off small annoyances and focus on what matters.

It's been three years since that Sloan-Kettering prom, and Mark has kept in touch with Conrad. She's in college, and her hair is long again. The girl who was pregnant is now the mother of two. Connolly and Burrows broke up, but both pursued their dreams after high school: He's a fourth-generation union electrician, and she's a pastry chef at Stephen Starr's Route 6 restaurant.

Six years after Mark captured them on a rapidly dwindling stock of 20x24 Polaroid film, Connolly and Burrows still have sharp memories of that June night at the National Constitution Center. "I remember every detail of it," Connolly says. "There was a balcony. To be standing out there, late at night, in the city of Philadelphia, in the spring air, in a dress, was fantastic. It was definitely a rock-star moment in high school."