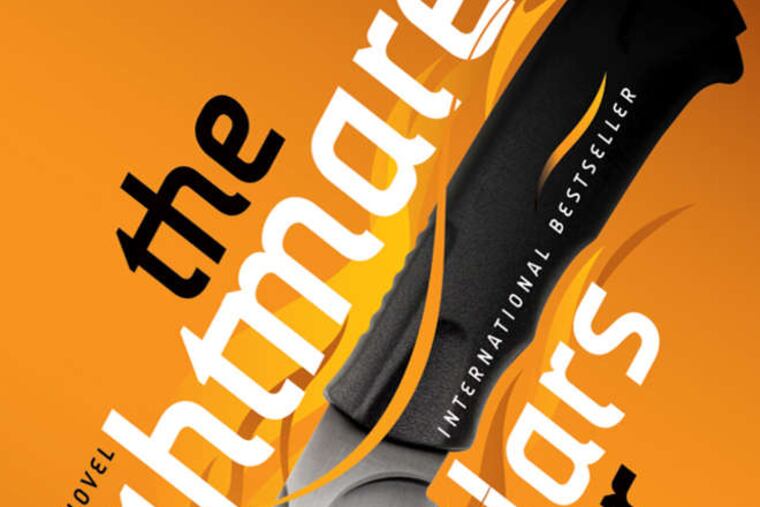

More from the Stieg Larsson school

The Stieg Larsson school of Swedish crime writing doesn't go in for guilty pleasures. Instead, it combines potboiler thrills and righteous anger in a fat, sprawling, tosh-filled package, often with 475 or more pages plus a didactic, statistics-filled epilogue in case the reader doesn't get the point - or in case he or she thinks the point was just to have some fun. That way the reader gets dirty thrills but feels morally uplifted at the same time.

By Lars Kepler

Translated from the Swedish

by Laura A. Wideburg

Sarah Crichton Books. 512 pp. $27

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Peter Rozovsky

The Stieg Larsson school of Swedish crime writing doesn't go in for guilty pleasures.

Instead, it combines potboiler thrills and righteous anger in a fat, sprawling, tosh-filled package, often with 475 or more pages plus a didactic, statistics-filled epilogue in case the reader doesn't get the point - or in case he or she thinks the point was just to have some fun. That way the reader gets dirty thrills but feels morally uplifted at the same time.

The Nightmare, second of Lars Kepler's novels to be translated from Swedish into English, offers one protagonist haunted by deep secrets. It has personal trauma, and it is fascinated with Paganini and with great old violins. It equates moral rectitude with musical ability, and it does so with a straight face. Talk about far-fetched, potboiler-y notions.

The solution to the central mystery, though that mystery concerns a political issue torn from today's headlines and involves government and corporate corruption, is straight out of Columbo. Quite naturally, the novel includes one especially horrible death. And then its prologue ranks the world's top arms-dealing nations, of which Sweden is said to be in the top nine.

There's nothing wrong with potboilers, and there's nothing wrong with politically engaged crime fiction. But it's fair to ask whether the politics and the potboiling are organically intertwined, or whether they appeal, separately, to two separate aspects of what the reader wants.

Dominique Manotti, Jean-Patrick Manchette, Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, and the great Leonardo Sciascia tell stories in which the politics and the thrills seem to emerge, inextricably bound, from the same reality. Among current Swedish crime writers, I would argue that Anders Roslund and Börge Hellström come close to achieving this in Three Seconds.

The Stieg Larssonites don't do this, and I don't think they try. I find their achievements less impressive than I do those of the authors I've just named, but this does not mean the Larssonians are any worse, just different. I can't blame an author for failing at what he or she may never have tried to do.

The invocation of Stieg Larsson is especially apt in the case of The Nightmare because Alexandra Coelho Ahndoril, the female half of the couple who write as Lars Kepler, has said that the Lars part of the nom de plume is a tribute to Larsson. Crime writing before The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo was all right, she said, but it had grown a bit stale.

I suspect this deliberate embrace of Stieg Larsson heralds a new sophistication in our understanding of Nordic crime fiction in the English-speaking world. Now that Larssonism - potboiler plots with didactic political intent; call it Harold Robbins meets Noam Chomsky - has emerged as a distinct mode of writing Nordic crime stories, perhaps we'll be spared further strained and fatuous invocations of such vastly different writers as Jo Nesbø and Håkan Nesser as "the next Stieg Larsson." And perhaps future writers will take Larssonism in interesting new directions.

The political target in The Nightmare is a worthwhile one: arms sales to the Sudanese government of Omar al-Bashir. This leads to a small but interesting deviation from political correctness. A young activist reporter flashes back to her time in the Sudan, to militia who raped and slaughtered Fur tribesmen and women in Darfur, to "three teenage boys shouting in Arabic that they were going to kill slaves," and the like. That's brave from a genre whose targets are likelier to include Western intelligence agencies or the Mossad.

Laura A. Wideburg's translation is generally smooth, though marred by a number of clumsy locutions, concentrated, oddly enough, between Pages 372 and 395 ("in spite of the fact that" rather than "even though," and so on). Any author or translator can have a bad day, but a copy editor should have caught the lapses.