An aging Inspector Montalbano grows more human

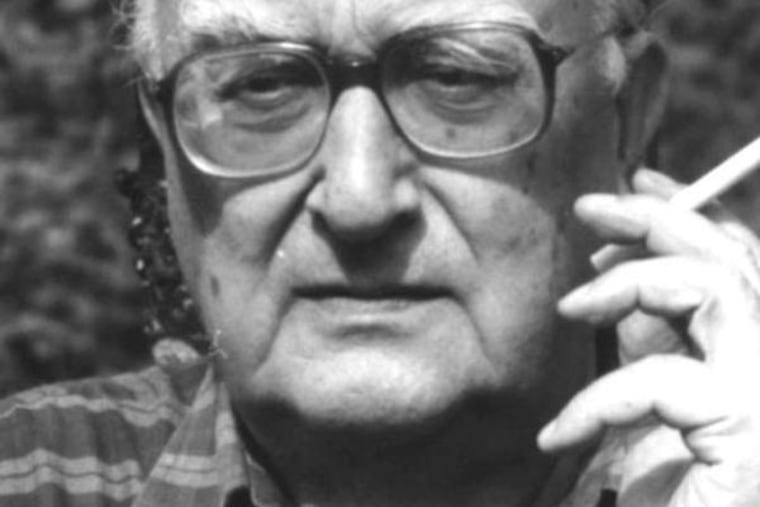

Fifteen books into his Inspector Salvo Montalbano series (with several titles yet to be translated from Italian/Sicilian/Camillerian into English), Andrea Camilleri manages both to offer readers the pleasures they've come to expect, and to vary the ingredients and add enough emotional depth to keep the series from growing tired.

By Andrea Camilleri

Translated from the Italian

by Stephen Sartarelli

Penguin, 288 pp., $15

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Peter Rozovsky

Fifteen books into his Inspector Salvo Montalbano series (with several titles yet to be translated from Italian/Sicilian/Camillerian into English), Andrea Camilleri manages both to offer readers the pleasures they've come to expect, and to vary the ingredients and add enough emotional depth to keep the series from growing tired.

In book 14 (The Age of Doubt), for example, Salvo is cursing the saints by the novel's second sentence. (It's a favored Salvo behavior.) In the Dance of the Seagull, he does not curse the saints until page 104, and for me the deferred pleasure is like that gained by letting a vintage port age just a few years more. ("Cursing the saints" is translator Stephen Sartarelli's rendering of the Sicilian santiare, a verb Camilleri's Spanish and German translators have lamely rendered as their languages' versions of to curse - or eliminated altogether.)

The Dance of the Seagull retains the acid-tipped social commentary that marks the earlier books, but the jabs, while sharper than ever, have become more human. The exasperated vitriol aimed at government and Mafia remains, that is, but it now lays bare more than it did before the human consequences of the misdeeds at which the narrator rails. That the central mystery here is the disappearance of Salvo's valued colleague, Fazio, only heightens the pathos.

Indeed, an increasingly empathetic touch makes the Montalbano books one of the rare long-running crime series that grow stronger with time, and almost certainly the most affecting. Camilleri was 68 when the first Montalbano book appeared, and he recently turned 87. The titles available in English have taken Salvo from his 40s to age 57, complete with amusing and touching descriptions of the aches and pains of aging.

In recent novels Salvo has grown more tender toward his lover, Livia, and more appreciative of what his colleagues mean to him. In The Dance of the Seagull, the humanity takes the form of Salvo's new revulsion at the savagery he witnesses while investigating three killings, and the introspection and empathy manifest themselves from the beginning. (The title refers to a seagull's dance of death that Salvo witnesses from his seaside home and that haunts him and his dreams throughout the novel. Camilleri integrates this dream into the mystery more skillfully than he has done in earlier books. He's beginning to get the hang of this Montalbano thing.)

But introspection and empathy need not imply surrender or resignation. Indeed, Salvo not only solves the murders and arrests the murderers, but he also manages to exact a bit of revenge from a powerful target.

Most moving of all, perhaps, is Montalbano's tendency to melancholy acceptance. The novel's blackmail/murder plot has drawn him into intimate contact with a woman he finds exciting - but he is deflated when the crime's solution means she need see him no longer. Salvo takes the news hard, but there is no room for self-pity or alcoholic dissipation in this fictional detective's world. The novel's last word, in fact, is caponata, a delicious conclusion.

The Dance of the Seagull also offers an entertaining Pirandellian nod to the internationally successful television series based on the Montalbano novels. Says Salvo to Livia:

"I wouldn't want to run into a film crew shooting an episode of that television series right as we're walking around there. . . . They film around there, you know."

"What the hell do you care?"

"What do you mean, what the hell do I care? And what if I find myself face to face with the actor who plays me? . . . What's his name - Zingarelli . . . "

"His name's Zingaretti . . . But I repeat: What do you care? How can you still have these childish complexes at your age?"

"What's age got to do with it?"

"Anyway, he doesn't look the least bit like you."

"That's true."

"He's a lot younger than you."