Tracing Updike's roots

In 1983, when John Updike was visiting his mother's Pennsylvania farm, freelance journalist Bill Ecenbarger wrangled an interview for The Inquirer's Sunday magazine with the author whose Rabbit Is Rich had won a Pulitzer and National Book Award a year earlier.

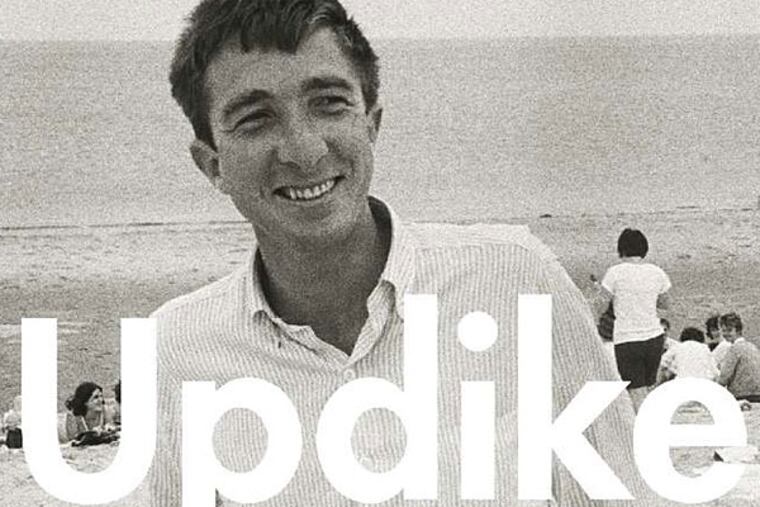

Updike

By Adam Begley

Harper. 558 pp. $29.99

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Frank Fitzpatrick

In 1983, when John Updike was visiting his mother's Pennsylvania farm, freelance journalist Bill Ecenbarger wrangled an interview for The Inquirer's Sunday magazine with the author whose Rabbit Is Rich had won a Pulitzer and National Book Award a year earlier.

It took place in the journalist's car - a VW Rabbit - as the novelist toured that corner of Berks County where he and his artistic sensibilities were nurtured.

The episode, the opening to Adam Begley's enticing new biography, Updike, was mutually beneficial. Ecenbarger got plenty for his piece. And Updike turned the encounter into a short story, "One More Interview."

That was not an unusual transaction.

Updike's life was his literary wellspring. Its details, no matter how private, not only informed his fiction, they became his fiction.

"We must write where we stand," he said in 1970. "An imitation of the life we know, no matter how narrow, is our only ground."

In this first serious biography of the Pennsylvania-born author, who died at 76 in 2009, Begley relies as much on Updike's fiction as on interviews, letters, and other documents. In doing so, he validates what devoted readers have long suspected: Updike's lyrical and prolific body of work was his autobiography.

The only child of mismatched Ursinus College graduates, Updike became a literary alchemist, incredibly adept at transforming his world's dross into golden prose.

Barely disguised, his homes in Plowville, Shillington, Ipswich, and Beverly Farms were constantly the settings for his short stories, poems, and novels. That work was populated by a familiar and virtually unchanging cast - his parents, classmates, teachers, girlfriends, wives, children, and lovers.

Nothing and no one was off-limits.

"The nearer and dearer they are," Updike admitted, "the more mercilessly they are served up."

Disturbingly, even the tearful dinner where he told his four children he was divorcing their mother became a short story and a poem; the latter, by the way, one of the rare Updike submissions rejected by the New Yorker, the magazine that inspired him as a boy and hired him as a young Harvard graduate.

That compulsion to "give the mundane its beautiful due" irked some critics, who, while acknowledging Updike's mastery of language and form, found the ordinariness of his subjects unworthy of great fiction.

"He seems a writer," Norman Podhoretz famously wrote, "who has very little to say."

Such proximity of fact and fiction is a biographer's dream. Begley employs both in dissecting the major events in Updike's life - the traumatic move from Shillington to the farm; the Harvard years, when his ambition shifted from art to literature; the brief New Yorker stint; his move from N.Y.C. to Boston's suburbs; his two marriages; his many dalliances; his divorce.

The Updike who emerges is far more complex than the gracious egghead his photos and interviews revealed.

Just as he created a fictional alter-ego in the Jewish intellectual Henry Bech to explore themes his Protestant, suburban self would not be inclined to examine, Updike himself presented a paradox.

Charming, he could also be ruthlessly competitive. Patriotic and religious, he wrote fiction that often exposed the meaninglessness of those attributes. A devoted father, he was a compulsive philanderer.

Updike's mother, a frustrated writer who ultimately published a few New Yorker stories, shaped him. Linda Hoyer Updike made it clear - as Allen Dow's mother does in the story "Flight" - that his talent demanded he make "the great leap of imagination up, out of the rural Pennsylvania countryside . . . into the ethereal realm of art."

But she also was responsible for painfully uprooting the boy from comfortable Shillington and depositing him on the remote family farm 12 miles away.

In a sense, Begley notes, Updike's entire career was a longing to return.

"[Shillington's] ordinariness appealed to the boy," Begley writes, "and it appealed also to the writer looking back on it, the writer who made it his business to "transcribe middleness with all its grits, bumps and anonymities."

A prodigy, Updike got nothing but A's at Shillington High, where his quirky, henpecked father - the focus of perhaps his son's most ambitious novel, The Centaur - taught math.

In 1950, he fulfilled his mother's prophecy by winning a Harvard scholarship. Before graduating, he had sold a story, "Friends From Philadelphia," to the New Yorker.

He would marry a Radcliffe student, spend a year in England on an art fellowship, then assume a New Yorker staff position. But "the corrupting influence of a certain big-city sophistication" troubled him, and by the 1950s, he and his growing family were in Massachusetts.

There, the disciplined author wrote every morning, read every afternoon, and became wealthy. Couples, the bawdy 1968 best-seller that made him rich, helped create the '60s "adulterous society."

Updike didn't just imagine the swinging lifestyle it portrays, he lived it. The quantity and depth of his affairs remains difficult to juxtapose with the image of the straitlaced, somewhat nerdy author.

The care and literary gravitas with which he garbed his adultery in fiction, Begley points out, might have been his way of justifying it.

"He was a lusty man," notes Begley, the son of novelist Louis Begley, a Harvard classmate of Updike's. "He had no scruples about adultery, yet he needed to dress up garden-variety infidelity as the inescapable consequence of some grand passion."

No matter how and where Updike strayed, his mind invariably returned to Shillington. In his last month - after lung cancer was diagnosed - hometown memories were again his theme. "Their meaning has no bottom in my mind," he had said.

"To put them down again on paper," Begley writes, "brought him a precious rush of happiness."

For his admirers at least, that's an apt description of reading Updike, which, as Begley's book confirms, was knowing Updike.

"The particular brilliance with which he made his autobiographical material come alive on the page," said Begley, "is part of the reward of reading him."