Out of the past, a timely tale

Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932 proceeds in one sense exactly as advertised: It is the story of lovers in Paris on the brink of World War II.

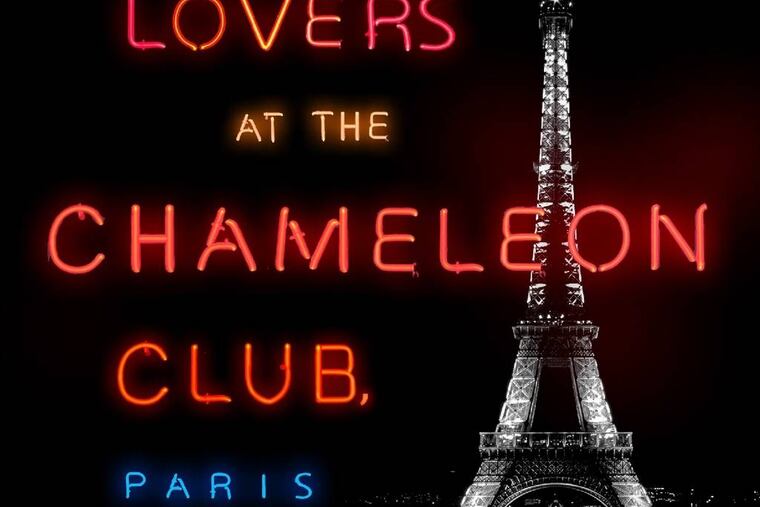

Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932

By Francine Prose

Harper. 448 pp. $26.99

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Elizabeth Langemak

Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932 proceeds in one sense exactly as advertised: It is the story of lovers in Paris on the brink of World War II.

Under its clothes, however, Francine Prose's formally inventive novel is the story of how stories get told and, subsequently, remembered. Like the girl dressed as a man on the Chameleon Club stage, the dance this novel performs is by turns sexy, illicit, and mystifying.

Prose will talk about her book Thursday night at the Free Library of Philadelphia in a joint appearance with Mona Simpson, who will discuss her new novel, Casebook.

Lovers at the Chameleon Club is a reminder of the empathic leaps needed to make sense of history, and also a question about the nature of empathy itself, regarding what people can accept, or even begin to understand.

Prose's 17th novel follows the friendships, love affairs and artistic, athletic, and political ambitions of its five main characters in a series of overlapping narratives. Each takes its own form: Gabor is a budding photographer from Hungary, presented in the letters he writes to his parents. His blowhard American friend Lionel writes a novel with himself as the hero. Suzanne, the love interest, and Lily, a baroness patron of the arts, write their own memoirs. Lou Villars, the book's main character, doesn't write at all, but is written about by her future biographer.

Tucked within are some delightful cameo chapters by minor characters arranged to simultaneously surprise the reader and fill in narrative gaps. The overall effect is of being a guest at one of the many champagne-filled parties the novel describes: The reader "hears" each character's story from many mouths, with new details coming to light as the night goes on.

At the center of Lovers stands Lou Villars, a cross-dressing, race-car-driving lesbian who spends her childhood in pursuit of athletic excellence and her adulthood in search of understanding, often in the wrong places. Prose has written elsewhere that the character closely mirrors that of the real-life Violette Morris and that she was inspired to investigate Morris' life when she first encountered the actual photo Morris once sat for with her lover. In this vein, one of Prose's cleverest innovations is how her book's title is also the title of this photo, fictionalized to be taken by Gabor at the outset of his career.

The fictionalized version of this historical photo comes to play such a complicated, controversial role in Lou's story that readers cannot help but want to see it, hoping to use it as a way of seeing Lou more clearly. Yet, by withholding a visual representation of the photo itself - it's not to be found in the text, nor on the book cover - Prose makes her readers complicit in the acts of imagination that Lovers both condones and warns against. Is it possible to responsibly imagine another person's inner life, even in part? Can we rewind an act of evil to find the innocent child at its core? For Prose and her characters, the answer seems to be that we must try, and we must know that we can fail.

Lovers is also a timely reminder that most stories about history are, indeed, timely. The tale of Lou Villars takes place in the shadow of Hitler, but the questions it raises about how we treat and mistreat those perceived as outsiders - particularly the LGBT community - are unmistakably contemporary. Like many of this book's most empathic characters, we often find it convenient to imagine that we live in an advanced world, in a progressive society, that our prejudices are few and our problems quite different from those of our grandparents. Certainly, this irony hasn't escaped Prose: The final chapter leaves no doubt as to the present-day implications of her story.

Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932 is a book with as much depth as length, though at more than 400 pages, it sometimes feels a bit too long. Additionally, a few character voices sound nearly interchangeable in tone, though the reader who would harp too long on this point strikes me as someone who would pass over the chance to live in a beautiful, many-roomed house merely because the kitchen is painted in the same shade as the living room.

Lovers reminds us the best stories aren't the ones we hear once, but those that come to us many times over, repeated until even their true parts bear the qualities of fiction. They're also the ones we can't possibly know all of. This powerful, perceptive book offers these truths, and - even better - a great story to shroud them.

AUTHOR APPEARANCE

Francine Prose, "Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932," with Mona Simpson, "Casebook"

7:30 p.m., Free Library of Philadelphia, 1901 Vine St.

Tickets: $15, $7 students. Information: 215-567-4341 or www.freelibrary.org/authorevents.

EndText