Art: Jamie Wyeth, the inheritor, makes his own mark

After his father's death in 2009, Jamie Wyeth began to have a recurring dream that resulted in three large paintings of a landscape on the Maine coast, where men who were the artist's mentors overlook a turbulent sea.

After his father's death in 2009, Jamie Wyeth began to have a recurring dream that resulted in three large paintings of a landscape on the Maine coast, where men who were the artist's mentors overlook a turbulent sea.

Jamie Wyeth's grandfather, the great illustrator N.C. Wyeth, and his father, Andrew, appear in all three. The first also includes Winslow Homer, who knew a thing or two about painting ocean waves, but nevertheless looks a bit out of place, with Andy Warhol lurking in the foreground. In the second and best, Homer disappears. Warhol seems to be hiding behind a tree, Andrew Wyeth is pointing, and the water is a maelstrom of unnatural colors, such as acid green and lilac, and uncharacteristically violent brushstrokes. This sea is not so much about how the ocean looks as it is about the act of painting.

In the third, only the two elder Wyeths appear, vertical and inert, looking like permanent parts of the landscape, which, in a sense, they are. And where is Jamie? He's the one having the dream, of course, and it's a dream that only he could have then painted. He is the heir to a tradition, the last of the line of painters, the inheritor of the family business.

His paintings, like those of his father and grandfather, are exceedingly well-made. Yet he has not simply dwelt in the enchanted kingdom of Wyethworld. He jumped into the phenomena of his lifetime - space flight, the Kennedys, the Watergate trial, the tastemakers of Manhattan, and the libertine connoisseurship of Warhol's Factory, which seemed a denial of the conservative values the Wyeths seem to represent.

The exhibition now on view at the Brandywine River Museum of Art is the first full retrospective of Jamie Wyeth's work. It was originated at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts by curator Elliot Bostwick Davis, who wrote its excellent catalog. Usually, the Brandywine Museum has talked about Jamie Wyeth as part of a dynasty. This show offers an opportunity to consider him as an artist in his own right.

Clearly, his vision is not simply what was inculcated by his family, though he was home-schooled and taught to paint by his aunt Carolyn Wyeth. One sees many other influences, ranging from Thomas Eakins to Alfred Hitchcock. Even his dream seems inspired by a painting, Asher Durand's 1849 Kindred Spirits, which depicts the artist Thomas Cole, who had recently died, on a ledge overlooking a river valley with the poet and editor William Cullen Bryant. Like the Hudson River painters, Jamie Wyeth is a diligent recorder of the natural world. Look at those dragonfly wings, and at the little teeth inside the beak of a goose. And like them, too, his realism edges into the visionary and mysterious.

Wyeth, who is 68, was a prodigy who created some of his finest work when he was in his teens. Portrait of Shorty (1963) contrasts its unshaven, undershirt-clad subject with the luxurious wing chair in which he sits. What is astounding is the handling of the chair's brocade upholstery. You feel its smoothness with your eyes. It is an old master rendering of fabric, not to be expected from a youth of the 1960s. Portrait of Helen Taussig (1963) rivets you with the pioneering pediatrician's clear blue eyes. Her gaze is almost frightening in its seriousness.

Then in 1965 comes Draft Age, which shows Wyeth's closest friend from his teenage years in wraparound shades with a leather jacket over his bare chest. The technique is still breathtaking; you sense that you could stroke the leather jacket and feel every scuff. Yet it is a departure from the solitude and harshness of Andrew Wyeth's vision. It is sexy and theatrical, and clearly of a moment. The young Jamie Wyeth may have had old-fashioned technique, but he was living in the '60s.

That same year, Wyeth did yet another great portrait, this one of Lincoln Kirstein, who, largely through his patronage of others - notably George Balanchine - was one of the key figures in bringing modernism to America. He stands in the darkness with his back to us and his face in profile. One senses a rigorous and sensitive mind, always looking, and the painting puts the viewer in the best position: looking over Kirstein's shoulder.

The Kirstein portrait begins Jamie Wyeth's New York period, which eventually brought Wyeth into Andy Warhol's circle and produced memorable studies and portraits of Rudolf Nureyev and of Warhol himself. It is interesting to see Wyeth's portrait of Warhol next to Warhol's of Wyeth. Warhol, renowned celebrator of the superficial, shows the very handsome Wyeth with skin as flat and pink as a motel bathroom. By contrast, Warhol's blotchy face and direct but uncommitted gaze convinces us that we are seeing the man behind the mask and wig: vulnerable, kind, bourgeois.

New York turned out to be only a phase, however, and Wyeth has returned to his family's two landscapes, the Brandywine Valley and the Maine coast, for the rest of his career. He has painted sheep and dogs and goats rather than important cultural figures, but with the same care and empathy. One senses that, having escaped the shadow of his father for a while, he was freer to be a Wyeth.

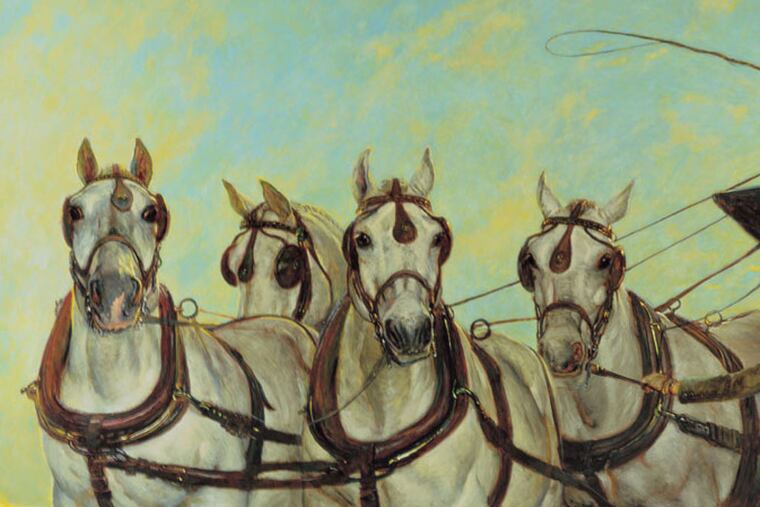

He had been taught painting in his grandfather's studio, full of props and costumes that N.C. used for his dramatic illustrations. Some of his grandfather's swaggering use of color and drama comes through in such paintings as Connemara Four (1991), which shows his wife, Phyllis, driving a four-horse coach. Here, the horses look right at us, like portrait subjects, while Phyllis looks away. The sky is enchanted, Wedgwood blue with creamy yellow clouds.

If you are Jamie Wyeth, you can't escape the influence of your family, and you may even have nightmares about where you fit it. What this exhibition shows, though, is that while the family tradition is visible in all he does, there is not another painter quite like him.

Art: JAMIE WYETH RETROSPECTIVE

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Hoffman's Mill Road and U.S. Rt. 1, Chadds Ford. 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily.

Admission: $15; 65 and over, $10; students and children 6-12, $6; 5 and under, free. Through April 5.

Information: 610-388-2700

or brandywinemuseum.org.EndText