'Paris at War' documents survival, uncertainty in Nazi-occupied City of Lights

On Aug. 26, 1944, after the surrender of German troops and police in Paris, the leader of the Free French movement stood at the top of the Champs-Élysées and addressed about two million people. "As far as my eye could see," he would write, "there was nothing but this swell of humanity in the sunshine, beneath the tricolor."

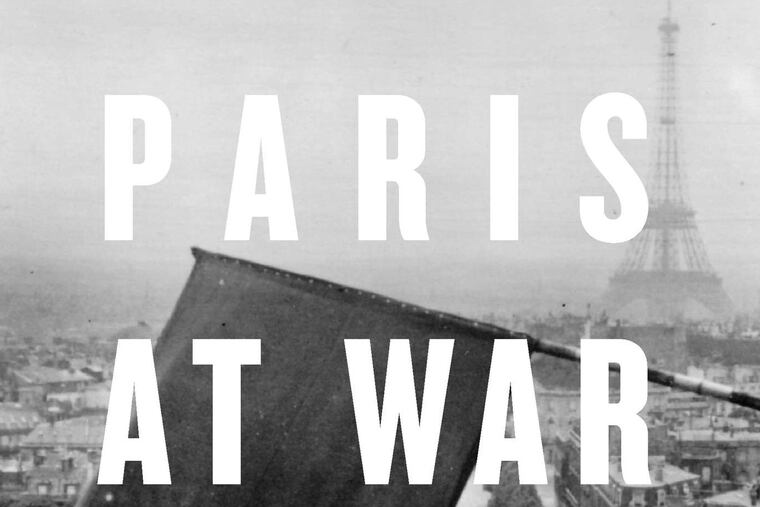

Paris at War

1939-1944

By David Drake.

Harvard University Press. 545 pp. $35

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by

Glenn C. Altschuler

nolead ends

On Aug. 26, 1944, after the surrender of German troops and police in Paris, the leader of the Free French movement stood at the top of the Champs-Élysées and addressed about two million people. "As far as my eye could see," he would write, "there was nothing but this swell of humanity in the sunshine, beneath the tricolor."

World War II was not quite over for Parisians. That night, German planes killed 120 people in a retaliatory bombing raid. And food shortages continued well beyond the official end of the war on May 8, 1945. But Paris had been liberated - and once again became the capital of France.

In Paris at War, David Drake draws on diaries and memoirs of Parisians, newspaper accounts, and radio broadcasts to chronicle life in the City of Lights during the German occupation. In a narrative that illuminates the day-to-day experiences of the rich and poor, collaborators, black marketers, Resistance fighters, Jews, and communists, Drake joins professional historians in pointing out that although a tiny number of Parisians (and French citizens throughout the country) were committed to either resistance or alignment with the Nazis, the vast majority were "attentistes" (taking a wait-and-see attitude), doing their best to survive under brutal conditions.

Drake describes the uneasy relationship between the Vichy government of Philippe Pétain and Hitler's lieutenants, as well as of the growth of the Resistance. His book is at its best, however, when he relates the perceptions and activities of ordinary citizens. Despite the casualties incurred in Allied bombing raids, Drake indicates, few Parisians blamed the British. Many more were outraged by edicts ordering hundreds of thousands of young men to work in Germany (ostensibly in exchange for French prisoners of war). And, we learn, Parisians evaded a ban on the use of electrical appliances in homes (energy was diverted to the Reich) by tampering with meters and replacing fuses removed by utility companies.

Drake demonstrates that Parisians responded in different ways to the repression and deportation of Jews. With the help of neighbors, and his non-Jewish wife, who ran their hairdressing business, Albert Grunberg remained in hiding in an apartment near the Sorbonne until Paris was liberated. On the other hand, some Parisians took "great pleasure" in naming Jews who refused to wear the yellow star. One Frenchman declared he could not care less if Jews were locked up but complained that he could not retrieve two pairs of shoes because the Jewish cobbler mending them had been sent away.

No Parisian could be sure how the war would end. Drake's engaging and informative book reflects this uncertainty - and invites us to ask what we would have done.

Glenn C. Altschuler is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American studies at Cornell University.