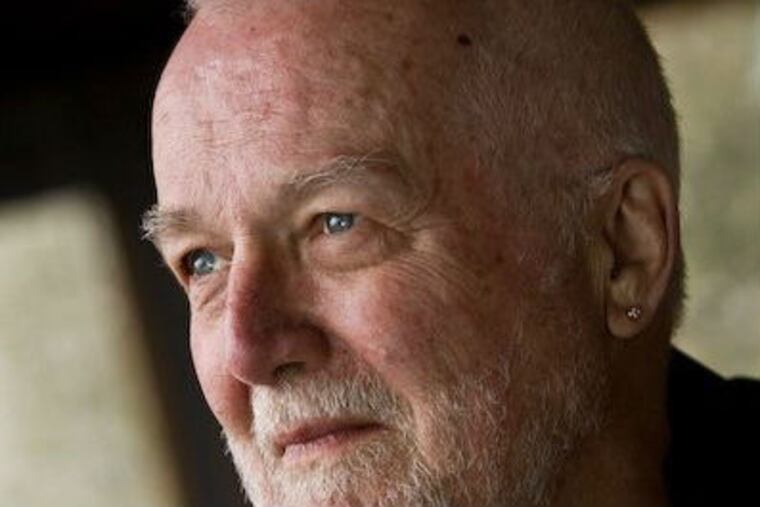

Russell Banks' 'Voyager': Self-indulgent, dodgy, open to wonder

There is travel involved in Russell Banks' Voyager: the Antilles, Senegal, the Seychelles, Himalaya, the Everglades, a college reunion; places and events come, they go, clamorous and chromatic, brimming with progressive commentary. But just as often, the road fades and Russell Banks looms: Enough about Dakar, let's talk about me. A memoir, then, in this case corrosive and dodgy, a travel memoir in which the two braids spark if rarely twine.

Voyager

Travel Writings

By Russell Banks

Ecco. 288 pp. $25.99 nolead ends

nolead begins

Reviewed by Peter Lewis

nolead ends There is travel involved in Russell Banks' Voyager: the Antilles, Senegal, the Seychelles, Himalaya, the Everglades, a college reunion; places and events come, they go, clamorous and chromatic, brimming with progressive commentary. But just as often, the road fades and Russell Banks looms: Enough about Dakar, let's talk about me. A memoir, then, in this case corrosive and dodgy, a travel memoir in which the two braids spark if rarely twine.

Banks brings an atypical perspective to this writing: that of a third-generation plumber with a yen to be a poet, a workingman's biting realism mingled with a freethinking that could happily pass the bottle or bong with antiestablishmentarians.

He brings keen eyes to his surroundings. One is peeled for what is wrong: environmental wreckage, packaged tours ("huge crowds of confused and suspicious and racially anxious white American tourists" - how does he know? maybe they're thrilled and open), and slavery's abomination. He calls Senegal's House of Slaves "the literal, physical place where the American imagination . . . was born."

That comment and others take some forbearance - unlike James Baldwin, whom Banks quotes: "One cannot claim the birthright without accepting the inheritance." Some of his observations are so self-conscious they don't really fly, as when we are told that historical preservation tells "lies about the past" that "disguise the present," or that fiction writing "has allowed me to keep on telling the truth, while avoiding anything like a confession." At moments like these, Banks indulges the words because he likes the way they sound.

He has another eye on people and place. There are gorgeous scenes in which Banks gets the color just right: a jet-black paradise flycatcher, the smoke gray of a black parrot. "The island was a purple carbon color," he writes, which hits a home run. Huge pink and red blocks of granite rise "out of the water and powdery sand and palmy hillsides," spontaneous, atavistic stone circles. He is a fancier of alleys and back streets, leading to intimate precincts and improbable events: "Two lines of beautiful tall girls and women leaping in time, turn and turn again, dancing brilliantly in torchlight."

Banks travels, too, into memory, a willful disinterment. He has been through three marriages that ended badly. All the journeys here will coax one or more of these relationships into an aching light, in which the cycle of marriage, divorce, and abandonment "felt like a serial crime to me. And marrying again was supposed to expunge my criminal record." But we also hear, "You're the first woman I've loved who doesn't need me more than I need you," a prelude to a big step backward, justifying the "flight from grief and rage generated in the women I loved by my inability to resolve the fundamental contradiction of their needing to be both the center of the universe and the universe itself, and their inability to acknowledge any metaphysical difference." Dodgy.

But Banks has another aspect, one that makes you want to hold him close. He is a sucker for delight, surprise, and wonder. Seeing a rare bird knocks him silly, and sea palms - which produce coconuts that Judy Chicago would have welcomed to her Dinner Party - give his circuitry a charge. And he turns back, twice, out of generosity and native smarts, from high peaks in the Andes; the second time, heaven help him, as a 60-year-old in Aconcagua's thin air, where he and the men he is climbing with witness a visitation: an angel, female, from Slovenia. You can think of 20,000 feet up as the kill zone, or the dreamtime, or you can heed Banks' traveling mantra: "when things screw up, as they always do, they usually get better."

Peter Lewis is book review editor of Geographical Review.