‘Boathouse Row’: Glorious tale of a Philadelphia landmark

I've always called the Schuylkill "she." I've had my reasons. She rises, she bends, she mirrors, she subsumes. She is surface and depth and history. Stand on a bridge and watch her flow. Walk along her banks; you'll never catch her.

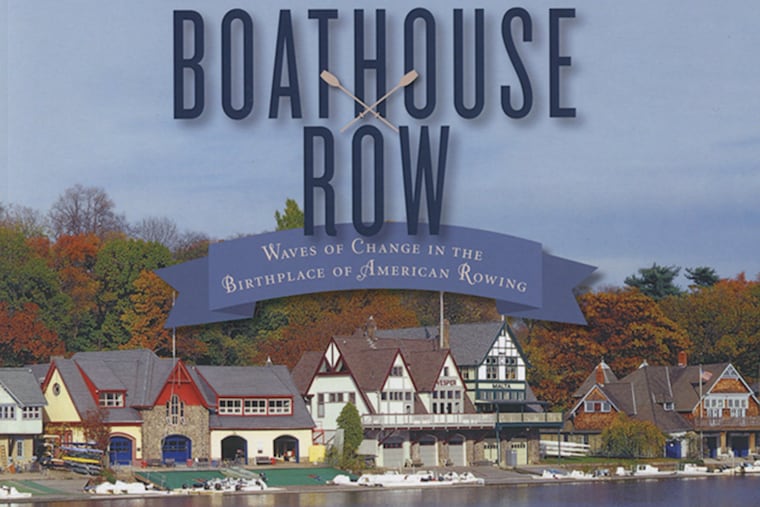

Boathouse Row

Waves of Change in the Birthplace of American Rowing

By Dotty Brown

Temple University Press. 275 pp. $35

Reviewed by Beth Kephart

I’ve always called the Schuylkill “she.” I’ve had my reasons. She rises, she bends, she mirrors, she subsumes. She is surface and depth and history. Stand on a bridge and watch her flow. Walk along her banks; you’ll never catch her.

In the late 1970s, Ray Grenald, a renowned lighting architect in Narberth, wondered what might happen if one of the Schuylkill's jewels - Boathouse Row - were illuminated with 8,000 incandescent lights. Grenald believed the city deserved such seductive imagery, and he found, in then-Mayor Frank Rizzo, a believer in this dream.

But once the lighting project got underway, Grenald and his team made a discovery: Many of the buildings "were firetraps, with underpowered and overheating electrical boxes. The first thing he did was order electrical work."

The story of Grenald's intervention in the fate of a Philadelphia landmark is one of many powerfully rendered tales in Dotty Brown's new book, Boathouse Row: Waves of Change in the Birthplace of American Rowing. Brown, a former Inquirer reporter, has spent three years, she tells us, going deep into the archives and out into the city searching for her story. Her tone is warm. Her voice is engaging. She focuses her attention on the yearnings, risks, and forces of change that have played a transformative role in the life of the Row.

Brown organizes most of her chapters around the beloved characters who effected lasting change in the sport and architecture of rowing. There's Thomas Eakins, the painter who was intent, Brown writes, "on capturing motion and athleticism." Controversial during his lifetime, met with mixed reviews, Eakins left behind a legacy of images that depict famed rowers like Max Schmitt (and Eakins himself) against the backdrop of an industrializing city. Eakins died in 1916, far too soon to see an expert at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art call him "America's greatest, most uncompromising realist."

Frank Furness is introduced as the architect behind the Undine Barge Club boathouse, a "fantastical yet functional" building that "escalated a competition of architectural one-upmanship along the Row even as it added to Furness' bold portfolio." Brown presents Furness as a mutton-chopped Union soldier who returns to Philadelphia with a "streak of recklessness" - a streak that gloriously translates into his unconventional work and river legacy.

No Boathouse Row book would be complete without the story of the Kelly family - that Irish clan who rose to fame and who, generation upon generation, gained prominence on the river. Brown delivers the Kelly story with a novelist's pacing. She explores the lasting legacy of champion rowers and collegiate coaches Tom Curran (of then-LaSalle College) and Joe Burk (University of Pennsylvania). The struggle for women's rights on the river is portrayed through a chapter focused on the great Ernestine Bayer. And the famed Vesper Eight, that motley crew that took gold at the 1964 Toyko Olympics, receives a chapter, too, with additional pages devoted to the philanthropists and visionaries who discovered, in the sport of rowing, a chance to create opportunities - and a sense of purpose and family - among city youth.

Generously illustrated and produced with great care thanks to a donation from H.F. "Gerry" Lenfest, Boathouse Row might have been a daunting undertaking - so much to research, so many decisions about which stories to tell and which to leave behind - but Brown's enthusiasm and personal knowledge of rowing grace every page, not to mention her deep interest in all the ways that chance decisions, discoveries, and characters are the stuff of which history is made.

Had Eakins not applied his intense interest in anatomy to the river paintings, we would not today see the late-19-century men and the light on the river as precisely as we do. Had Furness not been so happily reckless, the Row would not have half its current charm. And had not a lighting architect suggested a little boathouse illumination, the whole thing could have gone up in smoke.

The Row is still very much with us. And now it has Brown's history to further burnish its many charms.

Beth Kephart is the author of 21 books, including “Flow: The Life and Times of Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River” and “Love: A Philadelphia Affair.”