'Hidden City': Finding the Philly of the past

The authors of this book seek to recapture a sense of the architecture and social environment of what they term "the long nineteenth century" in Philadelphia. Building on the success of their Hidden City Festival - and the website Hidden City Philadelphia - the book advances the standards of "rich context and critical analysis" that Elliot, Popkin, Woodall, and company embody.

Philadelphia: Finding the Hidden City

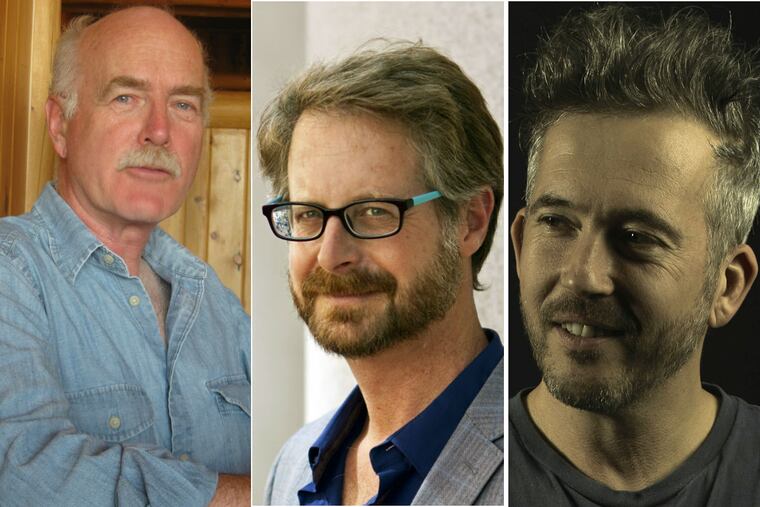

By Joseph E.B. Elliot, Nathaniel Popkin,

and Peter Woodall

Temple University Press.

200 pp. $40

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Jonathan Clancy

nolead ends

The authors of this book seek to recapture a sense of the architecture and social environment of what they term "the long nineteenth century" in Philadelphia. Building on the success of their Hidden City Festival - and the website Hidden City Philadelphia - the book advances the standards of "rich context and critical analysis" that Elliot, Popkin, Woodall, and company embody.

Divided into two parts, "City of Infinite Layers" and "City of Living Ruins," and replete with historic and contemporary photographs, the book offers glimpses of spaces and histories that remain unseen by residents and visitors alike. Elliot's sumptuous photographs are an essential counterpoint to the text - they transcend mere documentation and rise to the level of art. The book should broaden the audience for this trio's important work.

The book's strength lies in the authors' ability to peel back layers that are, "counterintuitively, highly conspicuous products of Gilded Age excess: civic monuments, polychromatic movie palaces, and colossal shopping bazaars." As time has gone by, far heavier stress has fallen on the city's Colonial history than what has happened since - so this recovery work is crucial to understanding the development of Philadelphia's urban fabric and how the present-day city arose.

Instead of attempting an all-encompassing history of these spaces and institutions, the authors smartly choose the specific over the broad, drawing the reader in through singular objects they use to speak for larger concerns. In Part One, for instance, the Wanamaker organ becomes a vehicle to discuss not only the history of the object and the store, but also the fate of urban retail and the role of historic preservation in saving narratives excised from history when buildings are removed. Similarly, the faded picture of Father and Mother Divine at the Circle Mission Biblical Institute engenders a larger discussion of religion, race, and the Gilded Age.

In Part Two, although the balance tips to the living city, Elliot's poignant photographs continually raise issues of history and meaning. Plate 2.4, of the gate locks at the now-abandoned Holmesburg Prison, is a fine example. The contrast between the heft of the late 19th-century locks and reinforcing bolts (designed to contain the incarcerated) and the slender chain and padlock (that now keep trespassers out) speaks eloquently to how material culture illustrates shifting social values, provided you look closely.

Despite the book's size, the text is notable more for its brevity than its depth. As such, it is neither the coffee-table tome that Elliot's photographs deserve, nor a probing history that sufficiently uncovers the hidden city of Philadelphia in the manner the authors promise. On both accounts, this is a missed opportunity. Elliot's images - particularly those of the Richmond Generating Station - deserve a format that allows the reader to explore their rich depth and detail. Equally important, many stories feel rushed, like the stunning decision of city planners (as late as the 1950s!) to use gravestones as an erosion barrier near the Betsy Ross Bridge. Consisting of two photographs and a single paragraph of text, this was one of many tales deserving more space. It is a part of Philadelphia history that in hindsight seems callous, macabre, and even irresponsible. In short, it is precisely the type of multilayered, hidden, and fascinating tale that a book such as this should not relegate to an aside.

Though Finding the Hidden City succeeds on many levels, there are shortcomings that should have been corrected in the editing process. Readers will notice that rather than addressing the "long nineteenth century" - a term coined by British historian Eric Hobsbawm for the period between 1789 and 1914 - the book is concerned primarily with Philadelphia's architecture and society from the Civil War through the Second World War. The list of plates at the end, which repeats verbatim the captions, is curious: A map of the places photographed, or footnotes for the abundant quotes, would have been far more useful. Despite these oversights, the book is an enjoyable reminder that the layers of history that surround us can speak eloquently about our past and present if we care to look and listen closely.

Jonathan Clancy is an art historian, author, and independent curator.