Centuries of Asian art, available on your phone

They chose a pretty piece for last. Photographer John Tsantes had placed Seated Princess - an opaque watercolor and gold painting that is part of the famed Islamic collection of the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery - on his table and focused the cutting-edge digital camera mounted overhead. And in the split second it took the camera's shutter to close, the museum completed a multiyear effort to digitize its 40,000-item collection.

WASHINGTON - They chose a pretty piece for last.

Photographer John Tsantes had placed Seated Princess - an opaque watercolor and gold painting that is part of the famed Islamic collection of the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery - on his table and focused the cutting-edge digital camera mounted overhead. And in the split second it took the camera's shutter to close, the museum completed a multiyear effort to digitize its 40,000-item collection.

The 400-year-old piece was the last of the works owned by the Smithsonian's Asian art museums to be digitally recorded. The images will go online Jan. 1, making this boutique Smithsonian the first of the franchise to share its entire collection with a global audience.

The milestone is especially gratifying to director Julian Raby, an early adopter of digital photography and an advocate of the Internet's power to transform museums.

"It's part of the democratization of art," Raby said. "John began what was the Smithsonian's first digital photography studio, so it's very nice that we are also the museum that is the first to digitize its whole collection."

Raby said the technology pushes the boundaries of what it means to be a museum because it allows for unrestricted study and enjoyment of the collection. Next month's release will include at least one image of each work - the majority in high-resolution - and the collection will be searchable and largely downloadable for noncommercial use.

Some of the galleries' most popular items will be available for download as computer and smartphone backgrounds.

Raby doesn't worry that putting the collection online will mean a reduction in visitors. In fact, he predicts the exact opposite.

"We strive to promote the love and study of Asian art, and the best way we can do that is to free our unmatched resources," he said. "I think it will intensify interest, and that will lead to more visitors."

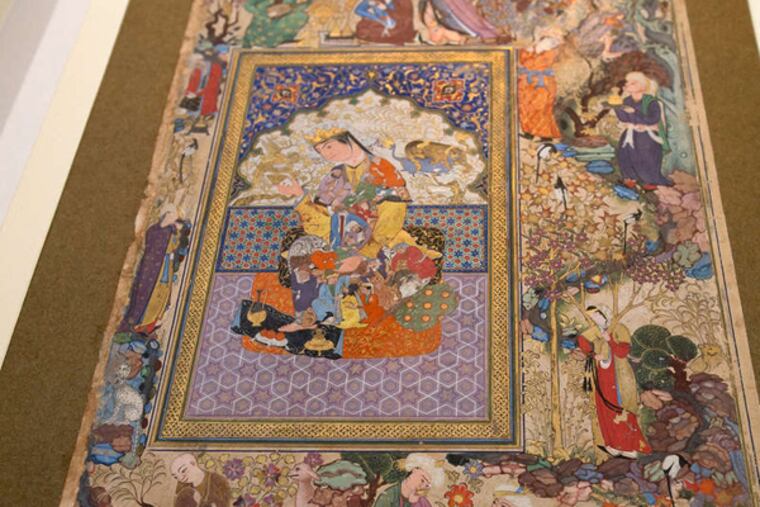

Courtney O'Callaghan, director of digital media and technology, said the last item was carefully chosen. A composite design featuring a woman in a robe surrounded by interlocking figures, it illustrates the value of the project: Although aesthetically and historically important, the work attributed to Muhammad-Sharif Musawwir is virtually unknown.

"About 78 percent of the collections have never been displayed. Now the public can see them, and in some cases, see them better," O'Callaghan said.

To illustrate the idea, Tsantes tapped the computer keyboard, and a section of the approximately 7-by-12-inch work exploded on the screen, the colors intense, the figures clear.

The technology allows the museum to standardize colors, O'Callaghan said. Each image is photographed next to a color bar with different hues numbered and therefore measurable. This removes the guesswork from the printmaking.

"It's instant, it's precise. And we have total control," she said.

It took many years and 6,000 staff hours to complete the collection. The museum's three photographers completed between 100 and 200 objects a week. Museum officials didn't calculate the cost; they said it was integrated into the regular work of the museum for many years and is impossible to estimate.

Although at least one image from every item in the collection will be posted online, the work of the photography studio isn't over. The museum continually acquires new pieces, and those items will be added to the online collection.

"This isn't the end of the work; this is the end of the backlog," O'Callaghan said.

In addition, staff members are working with new technology, trying to create 360-degree images of every three-dimensional artwork. As an example, the staff displayed a Korean ceramic pitcher. Still images were stitched together to create a short video panorama of the piece. In this way, the online viewer can get a better view of the work than a visitor to the museum can, O'Callaghan said.

Raby envisions that new research and even new artwork will result from the effort, fulfilling the museum's basic mission of preserving and sharing its masterpieces.

"Over the next few years, we'll figure out how we dive deeper," he said.