Art: Serving no one's vision but his own

In my experience, most retrospective exhibitions have a key work - one whose qualities and characteristics help me understand and appreciate the rest. For me, the key work in "Horace Pippin: The Way I See It," at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, is Harmonizing.

In my experience, most retrospective exhibitions have a key work - one whose qualities and characteristics help me understand and appreciate the rest. For me, the key work in "Horace Pippin: The Way I See It," at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, is Harmonizing.

This 1944 painting shows a quartet of African American men singing against a fence, beneath a light on a street in West Chester, not far from where the artist lived. The singers occupy the middle third of the painting, with a house and parts of other buildings visible on the right, and a church steeple peeking over the fence on the left.

The men's outfits are the first thing you notice, ranging from farmers' overalls to bright shirts to a jacket with light-colored pants - a sign that these singers do different sorts of work and live different sorts of lives. Once you have noticed the wildly contrasting stripes in the shirts and trousers, which ought to clash but somehow don't, it becomes obvious that the entire painting is filled with stripes.

The horizontal clapboards of the houses and sheds, with their contrasting colors, textures, and rhythms, are one set of stripes. The fence's vertical planks are another. The carefully delineated grain of the wood in the planks complicates the striping even more, and this verticality is echoed by the porch columns and the lightpost. This seemingly simple scene is formally complex and filled, perhaps like the singing, with unexpected rhythms.

These striations are something that reappear in much of Pippin's work, showing up as plank floors and log walls and other definers of the places where people live their lives. One unfinished work shows that Pippin drew these containing lines first, before filling in the details.

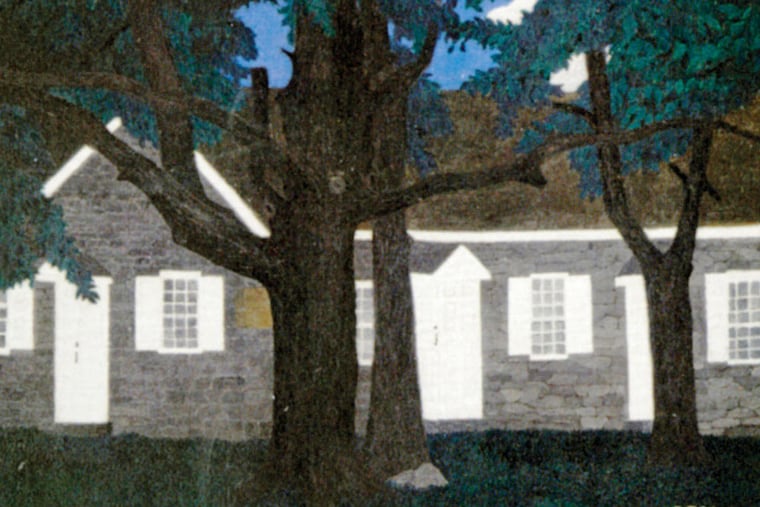

But though Harmonizing shows us the way Pippin thought about making space, it shares with the strongest works in the show a fascination with the particular. His paintings of the backs of West Chester rowhouses and of the Chester County Courthouse are abstract and stylized, yet they are entirely convincing evocations of the way it feels to be in those places. His three paintings of West Chester's Birmingham Meeting House capture, more than any depiction I have seen, the paradoxes of Quaker architecture - assertively nonhierarchical, modest yet permanent, a mishmash that turns out, despite itself, to be a monument.

And also, by the time he painted Harmonizing, Pippin realized that he was being called upon to help white America think about race. With its clashing that doesn't clash, and its black men, so clearly not all alike, he was saying that American harmony will always have dissonance.

Philadelphians are fortunate that some of Pippin's iconic works are on display here nearly all the time. Among them are the amazing The End of the War: Starting Home (1933) and Mr. Prejudice (1943) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; John Brown Going to His Hanging (1942) at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; and Birmingham Meeting House III at Brandywine.

The Brandywine exhibition, curated by Audrey Lewis, does not pack quite the wallop of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts' revelatory 1993 exhibition, curated by Judith Stein. Still, revelation doesn't come along every day, and after 22 years, Pippin's work is overdue for another look. Perhaps because the Brandywine is so tied to the local landscape, and the post-and-beam construction of its galleries even evokes Pippin's architectural settings, his Chester County paintings emerge here as profound expressions of the culture and landscape of our region.

But Pippin was never just a regional artist. He was, after laboring for a decade and a half to overcome injuries he suffered during World War I, an overnight sensation. The overwhelming majority of his paintings were created between 1938, when he was included in a show at the Museum of Modern Art, and 1946, when he died. Albert Barnes, one of those who "discovered" him, called him "the first important Negro painter to appear on the American scene." As the artist Kerry James Marshall notes in the introduction to the Brandywine's catalog, Pippin was received as a primitive, oblivious to the values of the art world, and also as a modernist, overturning the old rules.

If you look at his art, at least in 2015, both these propositions are laughable. Pippin was, in his way, very sophisticated, and attuned to the imagery and messages of popular culture, if not necessarily to the concerns of artists and critics. He knew, in short, that Gone With the Wind was a hit. And although the Brandywine catalog and its labels make a case that Pippin's several painting of slave families with cotton fields in the background question the antebellum nostalgia of the era, it is not at all clear that those who bought them saw such a critique.

Christmas Morning Breakfast (1945) is typical of Pippin's many scenes of African American domestic life, showing humble, yet neat, proud and orderly life among people in some bygone time. Collectors loved these works, and dealers urged him to do more. Today, his more personal and autobiographical paintings, such as his powerful World War I recollections and the enigmatic Man on a Bench (1946) appear far more moving.

In Christmas Morning Breakfast, the planks of the floorboards are vertical and parallel and occupy the bottom quarter of the painting. The effect, especially if seen close up or in reproduction, is a sense of precariousness. One feels that the boy, his mother, and all the furniture could fall out of their world at any moment.

Was Pippin making a psychologically astute observation of the insecurity many feel about keeping a good house and having a Christmas trees with presents underneath? Perhaps, but from across the gallery, the perspective works and the figures appear comfortable in their setting. Pippin was also doing a visual experiment, with a subject he knew would sell.

People were wrong then, and we would be wrong today, to look to Pippin to confirm preconceptions about race, about being primitive, or about being modern. That leaves us free to see him not as a spokesman or an example, but as a singular, compelling artist.

Art: HORACE PIPPIN EXHIBITION

Horace Pippin: The Way I See It

Through July 29 at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, Route 1 at Creek Road, Chadds Ford

Hours: 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily

Admission: $15; 65 and over, $10; students and children 6-12, $6; 5 and under, free.

Information: 610-388-2700 or www.brandywinemuseum.orgEndText