Art: Still – yet pulsing with life

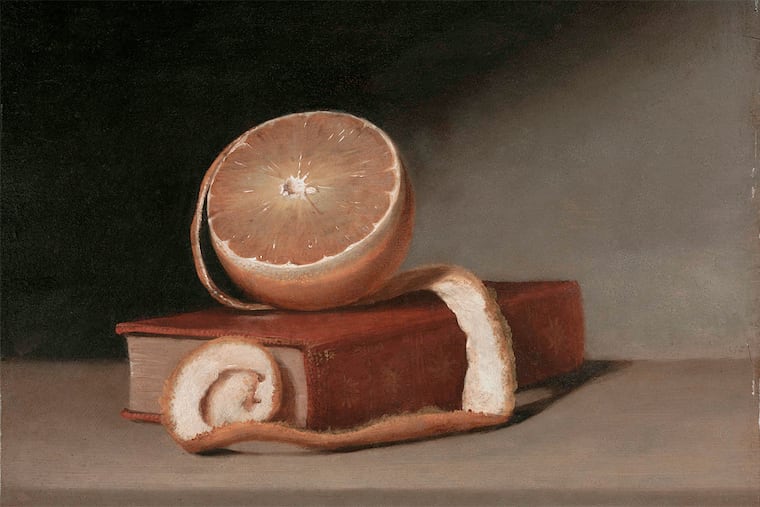

O ne of the first works to be encountered at the Philadelphia Museum of Art's wonderful new exhibition, "American Still Life: Audubon to Warhol," is an 1815 painting that shows a partly peeled orange sitting atop a book. The orange and its rind are so vivid you can almost smell its sharp sweetness; the peel spirals around the book like a snake.

O ne of the first works to be encountered at the Philadelphia Museum of Art's wonderful new exhibition, "American Still Life: Audubon to Warhol," is an 1815 painting that shows a partly peeled orange sitting atop a book. The orange and its rind are so vivid you can almost smell its sharp sweetness; the peel spirals around the book like a snake.

You can't help being struck by the odd juxtaposition. Why would Raphaelle Peale, who painted it, have done such a thing? You need to take a moment to scrutinize the work, both sensuously and thoughtfully, until it becomes clear this is not just a decorative painting, but a manifesto. It asserts that there is as much knowledge, and even wisdom, to be gleaned from the close observation of something so humble as an orange peel (or perhaps a Peale) as from the weightiest tome. Peale's orange is more than real; it feels true. (And Peale's blackberries, nearby, are even better.)

Peale, one of the many children of portraitist and naturalist Charles Willson Peale, worked almost exclusively as a still-life painter, an artistic specialty that brought less respect and lower prices than did portraits or history paintings. Yet, as his works in this exhibition show, he was a master. And in his preoccupation with things - his drive to show things as they actually are, to suggest what they might mean, and to call attention to the illusory nature of his own creations - he was a profound explorer of an emerging, uniquely American culture.

Similarly, an exhibition of American still life might seem to many merely trivial and decorative, or something just for specialists, and in any case skippable. Quite the contrary, this show is beautiful, engaging, surprising, thought-provoking, and not to be missed.

Organized by Mark D. Mitchell, who was until recently associate curator of American art at the Art Museum, the show is large, with about 120 works by familiar and unfamiliar names. Many reward contemplation; each bowl of fruit hints that it is something more. The show defines still life broadly as the painting of things, though it includes some works, notably those by John James Audubon that depict animals in the wild, that clearly do not fit any reasonable definition of still life. Nevertheless, it is good to see works like Audubon's watercolor of a Pennant's marten, or fisher, which is fierce and frightening, yet has every hair on its back rendered in delicate detail.

Still, Audubon, like Peale, straddled science and art and created illusions with such precision his subjects seem to be definitive depictions. Through their particularity they embody the ideal.

The show's premise is that through still-life painting, and a handful of sculptures, artists have explored that most fundamental American preoccupation: materialism. Things have always been important to us, perhaps because we were severed from traditions that long animated European painting. An Italian might have explored spirituality in a Madonna and child, but the American seeks transcendence in the fuzz of a peach.

I have written four books about the paradox of American materialism: We don't care so much for the things themselves as for the ideals - progress, freedom, individuality, mobility - that they represent. We care deeply about things but rarely hesitate to throw them away when a new avatar for our aspirations comes along. Thus, the selling and buying of stuff dominates our culture and our lives.

Unusually, for a show of American paintings, the earliest works, from the first third of the 19th century, are the most illuminating. The exhibition labels them as "Describing," and their scientific bent does distinguish them from the later works, which appear under the rubrics of "Indulging," "Discerning," and "Animating." Yet, an 1819 Peale painting of a bowl of peaches in which an insect seems to have landed on the surface of the painting, enticed by the fruit within, deals with the illusory nature of art as cogently as anything by the trompe l'oeil artists 70 years later. And Georgia O'Keeffe might have had a way with bones, but nothing she did was as animated as an 1804 drawing of a rattlesnake skeleton by Benjamin Latrobe, often said to be America's first professional architect.

We usually think of the mid-1800s, dominated by the Civil War, as a grim time, yet it was one in which many people got rich and wanted to celebrate their newfound abundance. The show has perhaps too many flowery pictures intended for the nouveau riche parlor, and food scenes for the dining room. But you will never see a more definitive celebration of abundance than Fishbowl Fantasy (1867) by Edward Ashton Goodes. In this over-the-top painting, the fishbowl, populated by several rather large fish, doubles as a vase overflowing with flowers and also reflects an urban street scene and, perhaps, a love story. By our décor you shall know us and believe us to be successful.

Salesmanship is pervasive in these paintings. Cezanne's stony little apples don't make the mouth water, but American platters overflow with watermelons, pineapples, grapes, and pomegranates, juicy, bright, and irresistible. Wrapped Oranges (1889) by William Joseph McCloskey shows us the same fruit as Peale did, but now presented as a luxury good. The orange is made all the more attractive and real by the little black spots and pimpling you would expect from a fruit right off the tree.

Americans worry about whether they are getting the real or the right thing. But we find it fun to be fooled, in part because the belief we are being conned makes us less responsible for our consumption. Artists like William Harnett and John Frederick Peto spoke to this anxiety and appetite with paintings that tricked the eye into seeing them as real and three dimensional. Harnett's paintings of money got him in hot water with the Treasury. He used a record high sale price ($4,000 in 1885) paid for After the Hunt to make it the painting everyone in New York had to see.

Like Mark Twain, who loved his scoundrels, Harnett and his fellow trompe l'oeil artists celebrated deception, and were celebrated for it in return. De Scott Evans' Cat in a Crate (1887) - a wooden box with a captive cat painted on it - shows that it's still fun to be caught off guard.

Speaking of deception, I should warn you about the title of the exhibition. "American Still Life: Audubon to Warhol" contains only one Warhol, and it's one you've probably already seen, the Brillo box. The naming represents slightly shady salesmanship, which, as the exhibition makes clear, is part of the American tradition.

The good news is you don't need to see Warhol yet again. See this.

Art: STILL FULL OF LIFE

StartText

Audubon to Warhol

Through Jan. 10 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 26th Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

Hours: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday; to 8:45 p.m. Wednesdays and Fridays.

Tickets: $20; 65 and over, $18; students and 13-18, $14; 12 and under, free.

EndText