'Dangerous Mystic': A true, gripping tale of a man's perilous search for God

Joel F. Harrington's "Dangerous Mystic" tells the story of a Dominican friar who, in the 14th century, taught that we can find a way to God by ourselves.

Dangerous Mystic

Meister Eckhart's Path to the God Within

By Joel F. Harrington

Penguin. 384 pp. $30

This book tells one of the strangest, and most strangely affecting, stories of the Middle Ages.

It might also seem strange that such a book would be written now — a wonderfully smart, readable biography of a 14th-century Dominican priest and mystic named Meister Eckhart — except that Eckhart has become something of a pop-cult hero. He's medieval, but he's also 2018. His philosophy has been adopted by Catholics, Protestants, Buddhists, Muslims, everyone from New Age thinkers to existentialists like Jean Paul Sartre, folks at odds with one another but sharing an attraction to his cosmic vision.

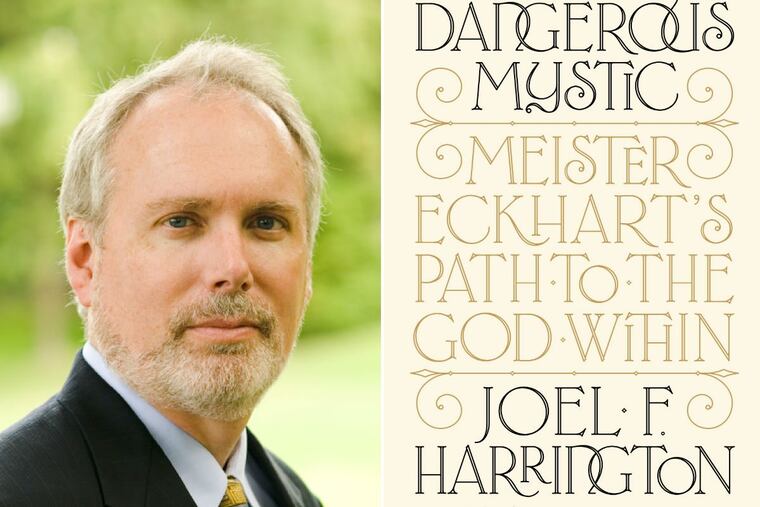

Author Joel F. Harrington just got a Guggenheim Fellowship, and many of the reasons are on display here. Here is a scholar/storyteller who can tell a true tale that feels like a novel, without cheap tricks. The opening, in which Eckhart delivers an epoch-defining sermon in 1318 at the cathedral of Our Lady in Strasbourg, is especially beautifully rendered.

Here is where we first learn his central message: "Anyone who was spiritually ready could experience the birth of God directly within his or her own soul."

Doesn't sound like much? Not in 2018, maybe, when every other contemporary spiritual teacher says more or less this. In 1318, however, it was dynamite. Thus the title, Dangerous Mystic.

Harrington explains the danger by painting a vibrant picture of the times and places in which Eckhart moved, prayed, and taught. I'm going to be blunt about it. Technically, Roman Catholics are generally warned against being true mystics — people who seek a direct union with God. You're supposed to go through the front office, so to speak: the sacraments, the teachings of the church, the authorities.

That, of course, explains the great gallery of Catholic mystics all through the history of the faith, including Meister Eckhart. He taught there was a way to God and that we could get there. It wasn't easy: We must let go of all external impediments, achieve a state of nothingness. Sacraments, good works, churchy things, not so much. We can get there on our own, if we only will.

As Harrington masterfully shows, the 14th century was a dynamic time. As he takes us through the facts of Eckhart von Hochheim's life, he sets them within the struggles over the papacy, the religious and philosophical disputes that marked the era, population growth, feudalism, and Eckhart's rigorous training as a Dominican. Eckhart was part of an international grassroots movement, longing for noninstitutional union with the divine. The English anchoress Julian of Norwich wrote the Revelation of Divine Love in the same century, the first book in English by a woman we know of. And the anonymous English book The Cloud of Unknowing, which also teaches the hard way to shake off everything and connect with God, "who can be loved but cannot be thought," often sounds very much like Eckhart. There was a great, upwelling longing to connect … and a hope that maybe we can tiptoe around the guards at the gate, circumvent the authorities who terrify us with death and eternal punishment.

Of course, teaching that you, in effect, can tiptoe around them … that risked angering the church.

After a career garnering respect as a scholar and theologian, Eckhart is brought down by rumors, backbiting, and accusation from fellow clerics. He is hauled before church questioners, and his disdain is evident: The charges "demonstrate the mental weakness and spite of my adversaries." (That's a bad way to conduct yourself before a tribunal that has capital power.) "To imply that man cannot be united with God … is against the teaching of Christ and the Evangelist," he says, sincere and furious. An appeal is denied, his case goes higher up the chain … and the church would clearly have put him to death had he not died before it could. Pope John XXI did stamp on his grave, condemning him in a papal bull.

We leave with considerable affection for Eckhart, and plenty of questions. Although he protested that all his opinions were "orthodox," he clearly knew the risks he was taking during his 10 years of dangerous teaching. Aspects of his thinking are elusive: the "oneness" of God, the "birth" of Christ in each of us (meaning exactly what?), the nature of the afterlife, the "nothingness" of ourselves-in-God.

What touches us is his powerful sincerity, and his resonant sayings, such that "anyone who prays for anything in particular prays badly." True, that. At times, Dangerous Mystic has a Name of the Rose excitement to it, a man against the grain during a time of ferment, a mind that sought to rise above it. Dangerous Mystic is likely to make Eckhart even more of a hero to more people. Good.