John Kerry’s ‘Every Day Is Extra’: Skimming the surface, with lack of insight

The former senator, secretary of state, and presidential candidate is often interesting in this autobiography, but he avoids the deeper questions about his upbringing and the state of politics today — with the exception of his service in Vietnam, where he writes vividly and with outrage at his detractors.

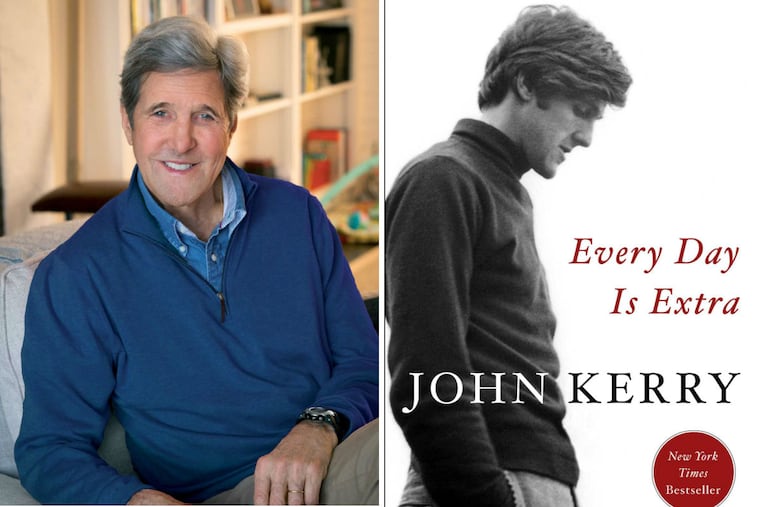

Every Day Is Extra

By John Kerry

Simon & Schuster. 622 pp. $35

Reviewed by Beverly Gage

At about 600 pages, John Kerry's autobiography offers a detailed account of his life from birth to the present, recounting his path from naval officer to antiwar activist to local politician and finally to Democratic presidential candidate and secretary of state.

This could have been a complicated tale, spiked with insight about the dilemmas of power or the challenges of legitimacy now facing America's liberal elite. But Kerry mostly skims along the surface, offering stories of boarding school and Vietnam and the campaign trail in an even, conversational tone. Many of those stories — especially about Vietnam and Massachusetts politics — are interesting, but the whole never quite manages to be greater than the sum of its parts. The book's title hints at a certain late-life humility, yet the memoir suffers from a lack of self-scrutiny on some fundamental political questions.

For example, Kerry does not engage persuasively with the major, inescapable fact of his birth into a life of privilege. Recall that this is a man who spent much of 2004 facing down accusations that he was out of touch with the people, windsurfing while the world burned. In his memoir, he remains surprisingly untroubled by this populist critique.

The same might be said about many other chapters of his life. One exception was his service in Vietnam, the most dramatic section of the book and ultimately the launching pad for his political career. After graduating from Yale, Kerry volunteered to serve as a naval officer and famously ended up assigned to the Swift boats, lumbering river patrol vehicles whose loud engines and difficult controls never quite lived up to the agile promise of their name.

Kerry evokes the tedium, thrill, and fear of Swift boat service, along with the anguish of losing close friends in an unwinnable war.

Today, he comes at the story with righteous outrage, not only about the poor decisions of U.S. leaders but also about the distortions and false accusations made by fellow veterans during the 2004 presidential campaign. "What still sticks in my craw is the way these men who served on Swift boats themselves turned the words Swift boat into a pejorative." Even here, though, he shies away from some knotty questions — including his decision to support the Iraq War more than three decades after denouncing Vietnam as a mistake and a national tragedy. Kerry ends up blaming George W. Bush for failing to deliver on commitments to diplomacy and multilateralism, but he reserves his greatest umbrage for the antiwar activists who split with him over Iraq.

"I was naive and overly optimistic to think that the activists would judge my record since 1971 … and stick by me rather than get behind someone who had never bled with them," he writes with indignation without quite addressing whether Iraq, in the end, turned out to be a repeat of what went wrong in Vietnam.

Kerry is at his best not in wrestling with such existential difficulties but in describing the dilemmas of on-the-ground politics: how to choose a vice presidential candidate, how to decide whether to accept public money. He recalls the 2004 race as the "last presidential campaign of a more personal era," when it was still possible for candidates to talk honestly with individual voters without worrying that the exchange would end up online. He harbors a certain nostalgia for the lost world of bipartisan Washington, where politicians of differing views tolerated one another at dinner or prayer breakfasts or in the Senate gym. When Kerry name-drops, it's often in homage to that bygone capital, where men like Ted Kennedy and John McCain could give as good as they got and still shake hands at the next cocktail party.

Unsurprisingly, Kerry aims most of his hostile fire at Republicans. Though he can't help admiring the party's strategic success, he worries about the decline of truth, virtue, and democracy that seems to have accompanied Republican rule. He views himself as the canary in the coal mine.

"It was amazing how low their party stooped," he writes of the 2004 campaign. "I had volunteered to go to Vietnam. Bush didn't. Cheney didn't." He concludes that "politics had clearly entered a dark, new chapter" by then and has been growing dimmer ever since.

For all of this partisan hostility, though, it's worth keeping in mind what Kerry and Bush have in common: Both came from wealthy, elite families with longstanding political ties; they even went to Yale at the same time. In recent years, Republicans have been adept at selling their high-born candidates as champions of the common man. Democrats, by contrast, have allowed themselves to be cast as insular elites, preaching to the masses while talking mostly to each other. Despite its value as the record of a life in politics, Every Day Is Extra will do little to dispel that myth.

Beverly Gage teaches U.S. political history at Yale.