‘Kudos’ by Rachel Cusk deserves kudos indeed

"Kudos" by Rachel Cusk completes her "Outline" trilogy, which includes the novels "Outline" and "Transit." Now that the superb "Kudos" is here, we can see this trilogy as one of the literary masterpieces of our time.

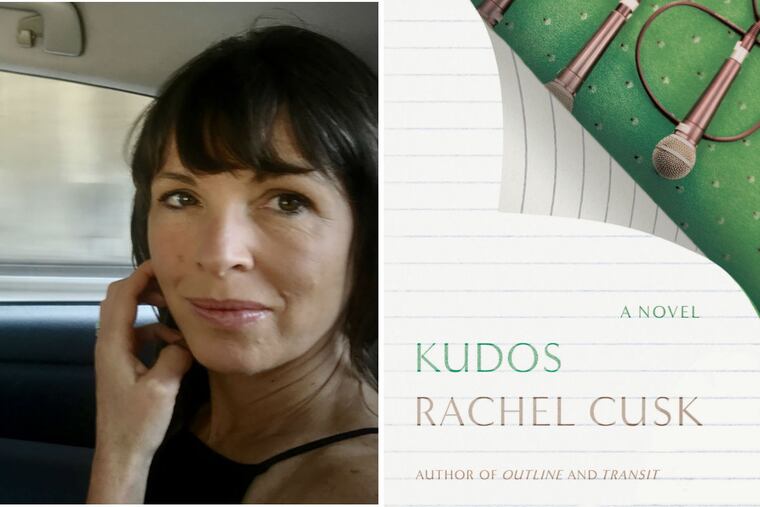

Kudos

Outline Trilogy, Vol. 3

By Rachel Cusk

Farrar Straus Giroux. 240 pp. $26

Reviewed by Sebastian Smee

When things fall apart, is it simply because our stories no longer ring true? Or do the stories no longer ring true because things are falling apart?

There is no right answer, but with her trilogy of post-calamity novels, Outline, Transit, and now Kudos, Rachel Cusk deserves accolades for asking so artfully. With the release of Kudos, these three novels can now be appreciated as one of the literary masterpieces of our time.

In each novel, the narrator, Faye (a novelist, like Cusk), describes her encounters with various people, each of whom has a story to tell. Faye recounts these stories, sometimes in direct speech but mostly indirectly.

But all this is really just a scaffolding. The stories are the thing. They revolve mostly around marriage, separation, and children. But each one reinforces, complicates, or undermines the others in a bewitching feat of theme and variation that is rich in emotion, suspense, and humor.

The stories are interspersed with brief, highly charged descriptions of Faye's immediate circumstances: the class she teaches and the boat she goes out on in Athens (in Outline); the London house she is renovating and the dinner party she attends (in Transit); and the festival she goes to in an unnamed urban port somewhere in Europe (in Kudos). If the central preoccupation of Outline was the question of self-definition, and of Transit the workings of fate, the theme in Kudos is success: Who will thrive? Who will get the prize? At what cost?

Faye remains inchoate, but it is not because we don't have a strong sense of her. It is because her own story remains unresolved. We are left to wonder whether she is destined to remain a blur, an entity without an outline, and if she is, whether this constitutes a freedom or a curse.

Are stories a product of the struggle to create meaning, as one character wonders? Or are they more often a mechanism by which to avoid responsibility, to assuage guilt? Undoubtedly, the narrative impulse kicks in hardest when our view onto the truth is most prejudiced – in the aftermath, say, of a calamity, a childbirth, or a collapsed marriage.

But such events also shatter the narrative. "What happened next," writes Cusk in the midst of an account of a skiing accident, "had to be pieced together from other people's accounts." The sentence reverberates like a plucked string throughout the entire trilogy.

Just as stories are inherently partial, the truth may be ultimately indescribable. The problem with such a conclusion – though it may be the only authentic one – is that it leaves the field wide open. And it brings us back to the question of which story, which fiction, will swarm into the vacuum and claim the prize (the house, the car, the new spouse, the kids)?

At the end of Kudos, one son tells Faye about how he and a friend accidentally started a fire in the basement of their apartment. It was an innocent mistake. What is hard, the boy tells his mother, is that no one listens to the full story when he tries to tell it. They fixate on broken fragments of narrative and apportion blame accordingly. It's unfair.

"You can't tell your story to everybody," concludes Faye. "Maybe you can only tell it to one person."

This moment of truth, and of love, lasts but a moment. It is obliterated by the book's – and the trilogy's – final act, which is such a violation, and on its face so crudely literal, that it all but annihilates the shimmering web of narrative, festooned with symbol and metaphor, that has led up to it.

Sebastian Smee wrote this review for the Washington Post.