Lafayette College scholar and colleague discover massive, unknown source of Shakespeare's plays

An unknown, unpublished 16th-century manuscript seems to have served as a major source for many of William Shakespeare's plays, ranging throughout his career.

It's huge news in the Shakespeare world.

It began as a detective story, a hunt for secret treasure, and a high-tech, computerized analysis of ancient texts — and now goes out to the court of public opinion for judgment.

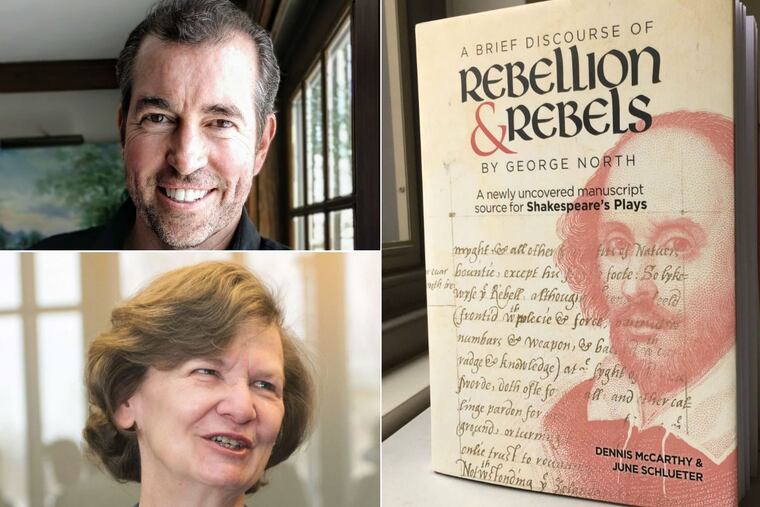

June Schlueter, a professor emerita of English at Lafayette College in Easton, Pa., and a coworker, independent scholar Dennis McCarthy, have discovered an unknown, unpublished 16th-century manuscript that seems to have served as a major source for many of William Shakespeare's plays ranging throughout his career, from Richard III to Macbeth. If borne out, their discovery would be the biggest Shakespeare source discovery in generations.

They've published that source, plus side-by-side tables of the original and Shakespeare's apparent use of it, in A Brief Discourse of Rebellion and Rebels by George North; A Newly Discovered Manuscript Source for Shakespeare's Plays (D.S. Brewer/ British Library, $120).

A Shakespeare "source" is a book, poem, essay, or tale that Shakespeare read and then reflected in scenes, characters, plots, echoes, and regurgitations throughout his plays. We don't have any of his books, but we can tell what he was reading. For Romeo and Juliet, for example, there's The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Iuliet by poet Arthur Brooke, which came out in 1562, about 35 years before Shakespeare's play. (I've held a copy and read the whole thing; trust me, the play is better.) We know a lot about Shakespeare's reading and borrowing; it's a scholarly industry. But seldom, maybe never, has there been a source this rich, covering so much of his career.

"The more people read the passages side by side, the more it will be accepted," McCarthy said by phone from his home in North Hampton, N.H. "I can't imagine it won't be. There are so many parallel passages."

George North, author of Brief Discourse, was a soldier, scholar, translator, and mysterious guy. In 1576, he wrote an essay, A Brief Discourse of Rebellion and Rebels, dedicated to a man who may have been a cousin: Roger, Lord North. At the time, George North was staying at Kirtling manor, the North family seat near Cambridge. His essay argues that rebels and rebellions are always bad, even if the leaders they're trying to depose are tyrants. Roger gave George five pounds while the latter was his guest, maybe as payment or a thank-you for the essay. George pops in and out of the historical record: He was ambassador from the court of Elizabeth I to Sweden for a time, and he published three books on politics.

Shakespeare must have known Brief Discourse pretty well. At least 11 of his plays show its influence, from the Henry VI trilogy at the start of his career (around 1590) to Coriolanus (1609). If all this holds up, this text may be one of the most influential on Shakespeare's work.

Here's what's exciting and crazy: The essay was never published. Until now, it's the only Shakespeare source that's never been in a book. It sat around, ink on paper, until …

"I was researching connections between the North family and Shakespeare," McCarthy said. "And I'd been looking for texts in the North library that might have been useful to him."

He came upon a 1927 auction catalog from a London rare books house, listing Brief Discourse. Some anonymous person had written a note: "It is extremely interesting to compare this earlier Elizabethan, George North's poems … with Shakespeare's treatment of the same subject in Richard II. And Henry VI, Part 2." Bingo. "I got so excited when I saw that," McCarthy said. "I had to email June immediately."

But where did it go? Someone must have bought it at some time, but there was no record. It could be anywhere. Needle, meet haystack.

"A frustrating year followed," Schlueter said, speaking from her home in Easton. "Dennis and I checked online catalogs for almost every college and university, hoping to find some reference to it, and we found nothing."

Schlueter contacted manuscript expert Anthony Edwards, and in two weeks he found it: in the British Library, which had bought it in 1933.

McCarthy and Schlueter know their Shakespeare, and as soon as they read North's essay, "the parallels and echoes leapt out at us," in McCarthy's words.

Now for the cool, computerized part. This is the era of big data in Shakespearean studies. Stylistic analysis is far more sophisticated than ever. In 2014, a collection of 10 plays appeared, titled Collaborative Plays by "William Shakespeare and others," tracing Shakespeare's uncredited hand in some of the best team-written works of the era.

In this case, McCarthy and Schlueter used WCopyfind, software usually used to detect plagiarism, to compare North's essay with Shakespeare's entire corpus. They found echo after echo: not only of individual words and phrases, but also rare words in close proximity, and used in the same context. (That's a big point; see below.)

McCarthy went further. He wanted to separate North/Shakespeare from the way folks generally wrote in their era, to single out their body of shared words from what was out there at the time. How? By using a database called Early English Books Online, or EBOO, which lets you search nearly all known publications from 1473 to 1700 — more than 60,000 texts — more or less at once.

"It really is like being in the greatest library ever," McCarthy says. "It's like having God as your librarian." What they found made it seem very unlikely that it was just chance, or the way people generally wrote, and much more likely that Shakespeare really was influenced directly by North's essay.

"It used to take people with really good memories," Schlueter says, "simply recalling where they had read something before. This is, of course, thousands of times quicker and more powerful."

Big deal. Shakespeare used someone else's words. Didn't he do that a lot? What makes this case especially powerful?

Schlueter and McCarthy say that it's not just the words, but also word clusters (groups of the same words used together), used when talking about the same topic. Clusters and context. For example, North, discussing social disorder, lists different classes of dogs and compares them to different classes of people. At the top is the mighty mastiff; near the bottom is the lowly "trundle-tail" (a rarely used term). In Macbeth and King Lear, when characters are talking about social disorder (as North does) Shakespeare mentions, as North does, all close together, hounds, greyhounds, mongrels, spaniels, and (in Lear) the "trundle-tail." Rarities so close together in the same context "yield you a likelihood of billions to one, better than your chances of winning two lotteries in a row," McCarthy says.

Schlueter modestly calls McCarthy "the real brains of this outfit. He's that rare thing, an independent scholar, and as such he brings a freshness that's really needed in scholarship."

McCarthy says, "I probably would never have gotten this published without June's help. When people see her name, it makes easier the kind of serious consideration an independent scholar never gets."

But … OK, how did Shakespeare ever see this unpublished manuscript? Looking at all these echoes, you have to think he had it at elbow for upward of 15 years at least. In some dude's library in a manor house 70 miles (quite a schlep in those days) from London? Did he visit the manor house? Did he or someone else copy out the essay? Or did a third party somehow share it with him?

"We can't know for sure," Schlueter says, "but we think we know the best explanation. That," she says with a laugh, "is a subject for a book to come."

June Schlueter and Dennis McCarthy talk about their discovery on the Folger Shakespeare Library's podcast Shakespeare Unlimited: https://www.folger.edu/shakespeare-unlimited/george-north-manuscript