Leonardo da Vinci was a total misfit, and his biographer says that's part of his genius.

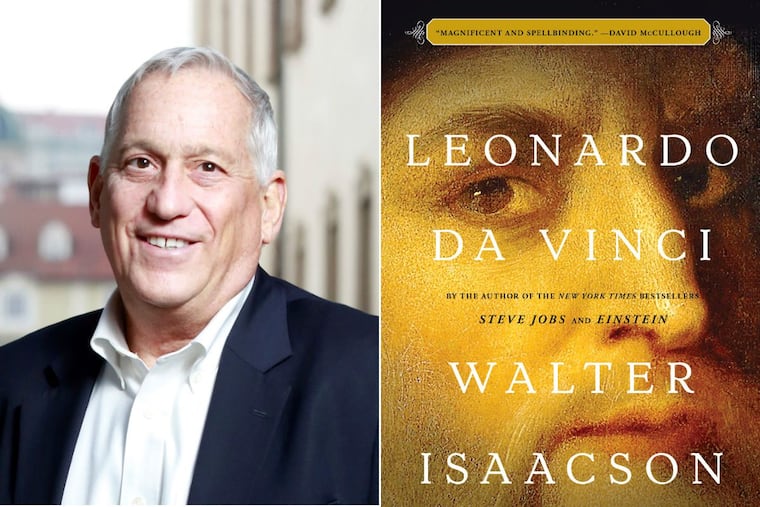

Walter Isaacson brings his new biography of Leonardo da Vinci to the Free Library of Philadelphia in a book talk Wednesday.

"He was illegitimate, gay, left-handed, vegetarian, somewhat of a heretic, a rebel. He was a real misfit."

Who was this man for no seasons? Leonardo da Vinci, one of the most famous human beings who ever lived.

And who's talking? His recent biographer, Walter Isaacson, biographer of geniuses, whose Leonardo da Vinci (Simon & Schuster, $35) is sure to wind up beneath many a holiday tree this year. Isaacson, also a biographer of Ben Franklin, Steve Jobs, and Albert Einstein, brings his vision of Leonardo to the Free Library of Philadelphia on Vine Street at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday (tickets: $15).

"And you know what?" Isaacson says by phone while walking in the rain in New York, "I think all these apparent handicaps actually helped him. They helped make him who he was." Example: Leonardo's illegitimacy barred him from his father's profession as a notary. "It also meant he couldn't be sent to one of the formal schools," Isaacson says. So he teaches himself, mainly, and becomes a disciple of experience.

"These things threw him on his own resources made him seek out learning and master it," Isaacson says. "If you can have a genius for curiosity, he had it."

And he had his moments, you could say. As in The Last Supper and Mona Lisa. Or "Vitruvian Man" (the man inside the circle). Or his mirror-written notebooks, which Isaacson calls "an absolute treasury of his daily thoughts and plans and questions." Or his plans for helicopters, cannons, fortifications. Or Salvator Mundi, a startling portrait of Jesus thought (controversially) to be by Leonardo, which at a Nov. 15 Christie's auction fetched $450.3 million, belittling the previous record for a painting.

For Isaacson, this misfit's value to history and humanity goes further: "Thinking for himself, Leonardo questions all received wisdom and says, 'Let me test that.' It's the beginning of the scientific method. He is the greatest forerunner of that method, in that he kept devising experiments to test his theories. And he was willing to revise his theories in light of new facts — it's what made Leonardo great. That and this desire to try to learn everything, a desire that spurs him to be an innovator in so many fields."

Even more than other figures of the Renaissance, Isaacson says, Leonardo "really tried to do everything, dissecting human hearts, designing waterways and flying machines, and painting two of the greatest paintings in history." It all goes back to that burning, cosmos-embracing curiosity. For him, the arts and the sciences were one: poetry and math, theater and engineering, painting and public works.

"Those notebooks are incredible," Isaacson says. "He lists all his questions to study that week. Why is the sky blue? How do the emotions get reflected in the expressions on the human face? Seeing the questions he lists, we can say, 'I can try that, try to be more observant in my daily life.' "

"Right at this moment, I am walking in Central Park in a light rain, noticing how water swirls as it runs off the pavement," Isaacson says. "That's the kind of thing Leonardo notes in his notebook again and again. In admiring Leonardo, I can push myself to be more curious, more observant."

How did Isaacson get his gig as genius biographer? "I sort of wandered into it," he says. He began with Franklin, "to understand the balance of power, diplomacy, and democracy better." He discovered what a great scientist Franklin was, so next came Einstein. "Then Steve Jobs said, 'Do me next,' and I realized I had to do him.

"When Steve Jobs did product launches, he'd run a slide at the end, showing the intersection of Arts and Technology Streets, and he'd say, 'That's where we stand,' " Isaacson says. "The secret of Steve Jobs lay in realizing that beauty matters in everything we touch. That same realization is prominent with Ben Franklin, and with Einstein playing Mozart on the violin to help connect him with the harmonies of the universe.

"I asked myself, 'Who was the ultimate in connecting all the disciplines?' And the answer came back: Leonardo, with the great emblem being the 'Vitruvian Man.' "

Strangely, and despite his global renown, it's still possible to feel a little sorry for Leonardo. His job applications and proposals met with disregard. He submitted plans for great public buildings. None were built. Many a book project was left half-done. He may have been the all-time drawing-board genius, leaving many potentially world-altering ideas right there.

"One of the rewards of studying Leonardo," Isaacson says, "is discovering how human he is. He just puts aside paintings that are giving him trouble. Some of his machines don't work. He didn't finish all his treatises. For me, that makes him more fascinating, rather than less."

Walter Isaacson: "Leonardo da Vinci"

Author appearance 7:30 p.m. Wednesday at the Free Library of Philadelphia, Central Parkway Branch, 1901 Vine St.

Tickets: $15.

Information: 215-567-4341 or freelibrary.org.