Rube Goldberg exhibit opens Friday: Meet the sly cartoonist behind the contraptions

The National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia celebrates Rube Goldberg, the man behind the unnecessarily complicated machines.

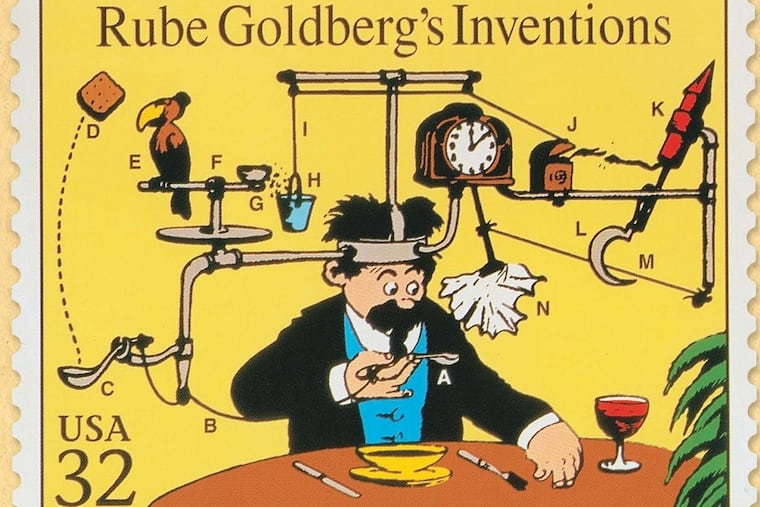

Just about the first invention Rube Goldberg never made was the Self-Operating Napkin.

Goldberg attributed the device to the genius of Prof. Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts, clearly a visionary, if not completely mad, and happily published a drawing showing how it worked.

In Goldberg's 1931 cartoon, which appeared in newspapers across the country, the napkin was shown deployed at the onset of a meal: "as you raise spoon of soup (A) to your mouth it pulls string (B), thereby jerking ladle (C)." And the directions end with a cigar lighter "setting off sky-rocket (K) which causes sickle (L) to cut string (M) and allow pendulum with attached napkin to swing back and forth thereby wiping off your chin."

Rube Goldberg was not sheepish about pyrotechnics and potential violence when employed for an ostensibly good cause, like facial hygiene. Nevertheless, the erstwhile engineer never made any of his thingamabobs.

"The Art of Rube Goldberg," the first comprehensive exhibition of the great cartoonist's work since a retrospective at the Smithsonian Institution in 1970, the year of his death, is now poised to open at the National Museum of American Jewish History, Fifth and Market Streets.

More than 30 of his famous invention drawings will be featured, but the exhibition covers the entire sweep of Goldberg's career, from the earliest days and his first cartooning hits, like "Foolish Questions," to his post-Second World War political cartoons. The exhibition runs from Oct. 12 through Jan. 21.

>> READ MORE: Our critics pick the season's best museum shows, concerts, festivals, movies, and more

Josh Perelman, the museum's curator, said Goldberg "lived in some of the most transformative times in world history" and engaged with one of its most mind-altering features: "how technology transforms human experience."

That industrial marriage of man and machine propelled Goldberg into celebrity. He became one of the most popular cartoonists of all time, and his invention drawings had such a broad appeal that the phrase "Rube Goldberg machine" entered the lexicon sanctioned by Merriam-Webster's, which defines Goldberg's name as "accomplishing by complex means what seemingly could be done simply."

Goldberg himself characterized his machines as growing from a somewhat darker impulse to become "a symbol of man's capacity for exerting maximum effort to achieve minimal results."

Take the "Self-Operating Napkin." It held the diner in place and employed a variety of harrowing elements: explosives, scythes, and fire. It was also fundamentally funny.

Goldberg's pal Charlie Chaplin, in consultation with the cartoonist, brought out even more humor and horror with a device directly inspired by the napkin. In Modern Times (1936), one of the funniest scenes in all of movies depicts assembly line worker Chaplin dragooned into testing the Billows Feeding Machine.

The boss has been impressed by the Billows sales pitch: "Don't stop for lunch, be ahead of your competitor. The Billows Feeding Machine will eliminate the lunch hour, increase your production, and decrease your overhead."

Of course, the machine goes haywire, the captive Chaplin ends up covered with soup, lug nuts are crammed into his mouth, his face is splattered with cream pie, and the boss deems the machine "impractical." He walks off.

Chaplin's great film brought out what is latent in the Goldberg cartoon: That the 20th century embodied the fusion of man and machine, mostly to man's detriment. There was no escape. The human landscape was fast becoming a mechanical landscape of production all fertilized by indifferent capital.

Goldberg, who was born in San Francisco and moved to New York as a young man to make his way at the center of the media universe, made all of these points with great subtlety. He played it for knowing laughs and was rewarded with riches.

But at the end of the Second World War, he became increasingly focused on political cartooning, winning the Pulitzer Prize. The stakes were too high, he felt, to leave politics to the politicians.

Interestingly, there has been a huge resurgence of interest in Goldberg. Videos of Rube Goldberg machines proliferate on the internet, including the band OK Go's music video of This Too Shall Pass, which has been viewed more than 60 million times on YouTube. It features an elaborate device and a series of improbable actions that end with the band members being shot in their kissers with paint.

"You can get lost in Rube Goldberg machines on the internet," said Perelman.

These Rube Goldberg machines are infinitely clever, but they generally lack the social and cultural depth that interested the cartoonist. It's possible to get lost in the ingenuity of elaborate devices — and Goldberg, who had an engineering degree from the University of California at Berkeley — understood ingenuity.

But more often than not, his contraptions had a bittersweet point. It's no accident that he developed a career as a political cartoonist in the postwar years.

From his strips based on the shenanigans of Mike and Ike and Boob McNutt to his stark cartoons of a world teetering on the brink of nuclear war and Middle Eastern conflict, Goldberg never strayed far from the idea of simple catastrophe achieved via complicated human screwballs.

"This exhibition is a real opportunity," said Perelman, "to tell the story of the human we know as a staple of pop culture.