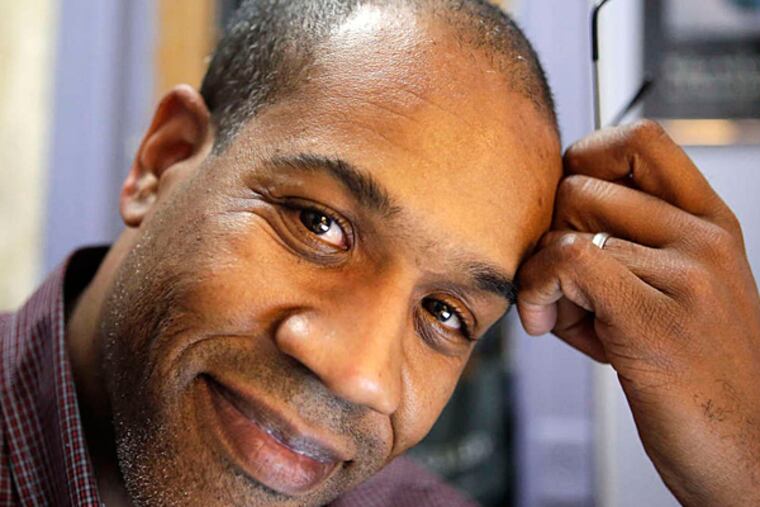

Philly-born Gregory Pardlo talks about his Pulitzer for poetry

After winning a Pulitzer Prize last week for his second book of poetry, Digest, Gregory Pardlo, Philly born and Willingboro-raised, says he's still a little delirious.

After winning a Pulitzer Prize last week for his second book of poetry, Digest, Gregory Pardlo, Philly born and Willingboro-raised, says he's still a little delirious.

"Each day I wake up thinking, 'Man, that was a weird dream,' " Pardlo says.

He heard the news in an ordinary setting: while waiting for his 10-year-old daughter after school. He got a congratulatory text message, and he thought it was for the Hurston-Wright Legacy Award he'd been nominated for a few weeks prior.

But that text was followed by another. And another. And another. When he saw the word Pulitzer, he says, "I just started panicking." He insists that "I only screamed twice."

Since then, Pardlo has been swept up in a whirlwind of interviews and congratulations. After a feature in the New York Times, he's been getting calls from agents and publishers.

Pardlo was born in 1968 in Philadelphia. His family moved to Willingboro after his father began work as an air traffic controller. At Willingboro High School, Pardlo played soccer, tennis, and the guitar - but, he admits, he was "distracted, directionless, and frustrated."

But then he was accepted to Rutgers University-Camden, becoming the first person in his family to go to college.

He started out as a political science major with plans of becoming a lawyer. But it was in his English classes that his love for writing and literature awakened.

At first, he didn't pursue it. As he says, "I couldn't imagine myself as a poet, writer, or as a thinker."

He dropped out and enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve, where he completed training in 1989. For Pardlo, who had been diagnosed as hyperactive, the Reserve was torturous but transformative. "Everything about boot camp," Pardlo says, "is sitting still and focusing."

Pardlo's break from college would last more than four years. He came back to Rutgers, studied abroad in Denmark, and helped run his family's jazz bar in Merchantville. There he met poets and jazz musicians. He even started a poetry-reading series. The passion those artists had for their craft inspired him to be honest with himself about his ambitions.

At that moment he realized: "I don't care if I'm broke. I know I can feed myself, I know I can shelter myself, and I want to write."

After some bumps in the road, he returned to Rutgers again in 1996. With the discipline he had learned in the Reserve, the sense of adventure he tasted in his travels, and the enthusiasm he caught from the artists he met at the restaurant, he returned with a new commitment.

Lisa Zeidner, professor of English at Rutgers-Camden and herself a novelist, had him as a student in a creative writing course.

"He was intense and serious about his own poetry but generous and engaged with his classmates," Zeidner says. "He showed early signs of understanding that poetry took a lot of work, and he was willing to do it." She says the poetry he wrote for class went beyond mere expression of his feelings to exploration of ideas. For his part, Pardlo says poetry "engaged both my rational mind and my intuitive mind."

When asked what he loves about poetry, Pardlo mentions the sounds, the shape of the words bumping together, the music. "I wanted the liberty to do that on the page," he says.

Pardlo earned an M.F.A. from New York University in 2001. Digest was conceived in 2004. He describes it as an effort to mesh academic with creative writing. He began writing the poems, but he says Digest wasn't officially a book until 2008, a year after he'd published his first book of poetry, Totem.

Paul Lisicky, a poet who met Pardlo at NYU, says by e-mail that he was elated when he heard about Pardlo's Pulitzer.

"He was always interested in writing a kind of poetry that made room for oppositions," Lisicky says. "A historical reference will sit up against autobiography, the global beside the minuscule, the raw beside the cooked." Pardlo says he makes use of his hyperactivity in the way he writes poems, constantly trying to "reinvent and not to sit still on any tone, formula, or style."

In Digest, Pardlo makes small moments large and brings large themes down to earth, telescoping from personal anecdotes to philosophy. In "Problema 4," a poem in Digest, Pardlo recalls his 13-year-old self asking his father for a tattoo. His father says no; he later reconsiders, but by this time the tattoo has lost its appeal. Pardlo sums it up with the line:

How can I beautify what I do not possess and call it anything but graffiti?

"Every word matters, there's nothing wasted or unnecessary," Lisicky says. "At the same time, the work never feels labored. The lines just breathe, as if they've come into being like music."

The title, inspired by Reader's Digest, might stand for how we synthesize or digest diverse arrays of information, from history to social media to the sciences to religion to popular culture.

Pardlo lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Ginger Romero Pardlo, and their two daughters. He is working on an essay documenting the effects of the 1981 air-traffic controllers' strike. He's also working on an M.F.A. in nonfiction at Columbia University. At the same time, he's pursuing his doctorate in English at the City University of New York; his dissertation is on visual culture in African American culture. He also wants to create a project involving alcohol addiction, his family, and the A&E program Intervention. His brother, Robbie Pardlo, a member of former R&B group City High, was featured on the show in 2010. Pardlo says he himself has faced alcoholism; being sober, he says, definitely helped in writing Digest.

Throughout Digest, Pardlo refers to his father often. He describes him as "hugely charismatic, with a big personality, overbearing, problematic, and all-embracing at the same time." In the book's final poem, "Kierkegaard," Pardlo describes a moment with him:

He is reaching out his hand. He is offering the last chance he may give you to be worth a damn.

If Pardlo's Pulitzer affirms anything, it's that he has made the most of his chances, and the world now knows what he's worth.

215-854-5054 @sofiyaballin