Biography of lawyer Jim Beasley falls short

Legendary Philadelphia trial lawyer Jim Beasley achieved national fame - and vast wealth - by magically spinning humdrum details into compelling courtroom drama. Former Inquirer reporter Ralph Cipriano's account of Beasley's life, unfortunately, too often

The Life of Legal Trailblazer Jim Beasley

By Ralph Cipriano.

Lawrence Teacher Books.

373 pp. $29.95.

Reviewed by David Marston

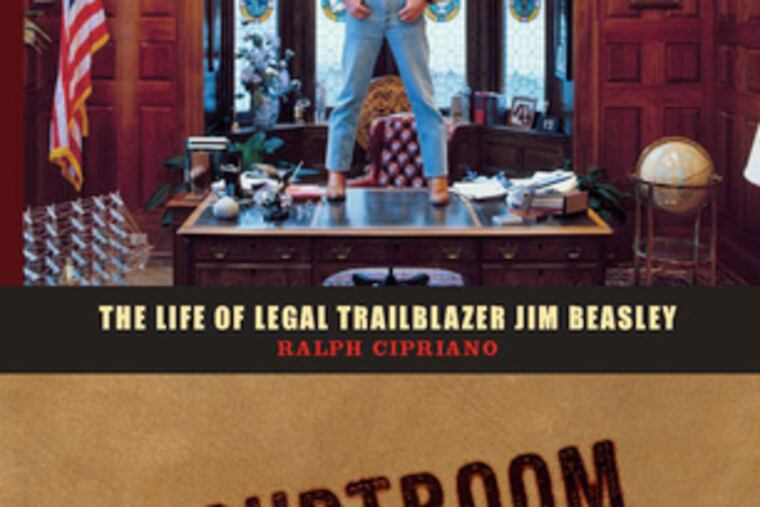

Legendary Philadelphia trial lawyer Jim Beasley achieved national fame - and vast wealth - by magically spinning humdrum details into compelling courtroom drama. Former Inquirer reporter Ralph Cipriano's account of Beasley's life, unfortunately, too often does the opposite. Indeed, Beasley seems most alive not in Cipriano's narrative, but rather in the book's spectacular color photos. There is cowboy Beasley, standing on top of his ornate desk, spoiling for a fight; Beasley and son Jim Jr., flying their beloved P-51 World War II fighters side by side, in a perfect, cloud-studded blue sky; hunter Beasley, scoped rifle in hand, kneeling beside a trophy zebra he bagged on an African safari; Beasley simply talking on the phone, the photo radiating his focus and ferocity.

Part of the problem is structural. The original book idea was for Beasley and Cipriano to write about Beasley's big cases, which are world-class: Epic battles against The Inquirer on behalf of Dick Sprague; Beasley versus boxing impresario Don King; Beasley winning a record $907 million wrongful-death verdict against fugitive murderer Ira Einhorn; Beasley as the first lawyer to serve legal process on the Taliban after 9/11 - followed by a $100 million-plus judgment.

It was a good plan.

But then Beasley died.

Still, Cipriano stuck with the one-case, one-chapter format. Deprived of Beasley's insights, however, Cipriano was forced to rely instead on juiceless trial transcripts, which are often stilted and obtuse. The result: a narrative that covers an impressively broad legal landscape, often interesting and insightful, but with a formulaic feel at odds with Beasley's verve and spontaneity.

Courtroom Cowboy

also aspires to be a traditional biography, and Beasley's outsize life and intuitive courtroom wizardry offer abundant material for such a book. Unfortunately, the author makes only a superficial effort to identify and analyze the forces that drove Beasley from childhood poverty to his remarkable successes. Cipriano often settles for a tiresome litany of adulatory comments, mostly from fellow lawyers: "Everything I am, I am because of Beasley." "He always had the smoothest talk. The adults, he would win them over." "The person I compare him to was Clarence Darrow. He wasn't afraid to take on anybody."

The character that emerges from such pabulum is almost a cardboard cutout, lacking the drive and competitiveness quintessential to Jim Beasley.

To Cipriano's credit, however, the Beasley he depicts is not free from flaws. Far from it. The lawyer's messy divorce, extramarital affairs, and rocky relations with his children are all there, and son Jim Jr. offers ironic perspective. Examples: Flying lessons and law school were a regular part of Beasley's seduction technique, leading Jim Jr. to observe that "Dad tried to turn all his girlfriends into pilots and lawyers." When his parents thought he needed counseling to cope with their tumultuous divorce battle, Jim Jr. said, "Look, I'll go, but why am I going? You guys need the counseling, not me." And perhaps most perceptively, Jim Jr. describes his father as "a combination of a hit man and a scared 5-year-old boy. It was one or the other."

Finally, it is worth noting that biographer Cipriano did not set out to write Beasley's biography. Rather, he set out to settle a personal legal score with The Inquirer, and he hired Beasley to do that. By the time his case settled, Cipriano writes, "I was so fond of my lawyer I didn't want to say goodbye" - not exactly the critical detachment of a biographer. Worse, the author seems equally unwilling to say goodbye to his own brawl with The Inquirer, writing on the book's jacket that his case was "the first time in American journalism that an editor was sued for libel by one of his own reporters."

Maybe. But the reader signed up for Beasley's story, not Cipriano's, and the first-person account of Cipriano's lawsuit near the end of the book is discordant and leaves the reader questioning Cipriano's true agenda.

The definitive Jim Beasley book remains to be written.

Jim Jr. might write it.