'Reagan and Thatcher' examines ties between two Cold War victors

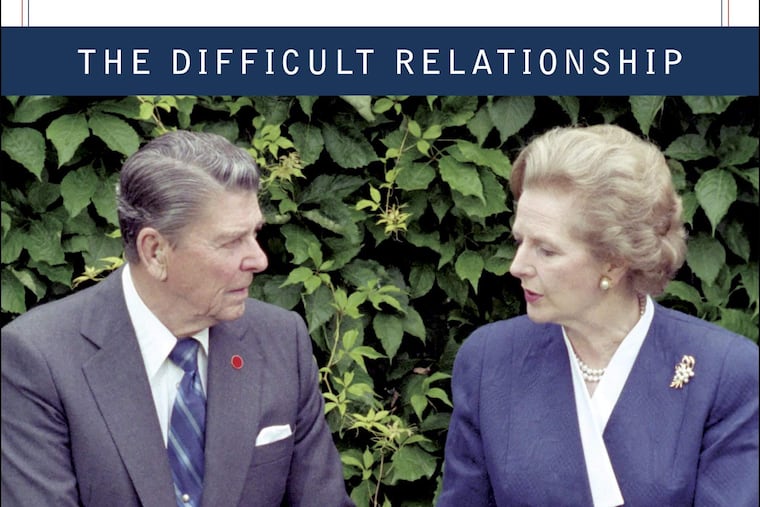

Reagan and Thatcher The Difficult Relationship By Richard Aldous W.W. Norton & Company. 342 pp. $27.95 Reviewed by John Rossi

Reagan and Thatcher The Difficult Relationship By Richard Aldous W.W. Norton & Company. 342 pp. $27.95

Reviewed by John Rossi

Otto von Bismarck, who forged a united German nation from an array of German-speaking states in the late 19th century, once observed that the key to the 20th century would be that Americans spoke English.

The so-called "special relationship" between the two largest branches of the English-speaking world proved decisive in two world wars. Now Richard Aldous, Eugene Meyer professor of British history and literature at Bard College in New York, sets out to examine how that relationship worked between two of the key political figures in the West's victory in the Cold War: Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

Aldous' subtitle tells all: It was a difficult relationship. Thatcher was genuinely fond of Reagan, a far different feeling than she had for his predecessor, President Jimmy Carter, who she believed had no vision for America. Reagan and Thatcher's closeness was based partly on ideology: both were conservatives who distrusted government and shared a view of the Soviet Union as an enemy that couldn't be ignored. Thatcher gloried in the name the Soviets gave her: the Iron Lady.

Aldous writes that they also shared and enjoyed being dismissed and underrated by the intellectual elites in their countries. Yet both came to be regarded as successful, transformative leaders, ranking among the most influential political figures in the history of their nations.

Despite their similarities, Aldous informs us that they approached politics with different styles. Thatcher was a formidable debater, knowledgeable and sure of herself. She made enemies and didn't seem to care. She dominated her cabinet, leading one wit to observe she was the only man in it.

Reagan, on the other hand, preferred consensus. When he took office, one of his first acts was to invite the Democratic speaker of the House, Thomes P. "Tip" O'Neill Jr., to the White House for drinks. The two got along well enough for Reagan to get most of his program through Congress. O'Neill noted in his autobiography that Carter had never invited him to the White House for a social occasion. In contrast to Thatcher, Reagan would resort to an anecdote from his past or a joke if discussions grew heated.

Aldous argues that despite a close, even warm, personal relationship, these two dynamic political figures often clashed on key issues in the 1980s.

When Thatcher launched the campaign to reconquer the Falkland Islands from Argentina, opinion in the Reagan administration was divided. The president wanted to support Thatcher, but at the same time, the American government feared communist influence in Latin America could be strengthened if the Argentine government collapsed. Similarly, when the United States invaded Grenada, the British were angry that they had not been consulted over an issue involving a part of the British Commonwealth.

The main issue that concerned Reagan and Thatcher was relations with the Soviet Union in what turned out to be the dying days of the Cold War. After becoming president, Reagan had not met with any of the Soviet leaders — he joked that they kept on dying on him. In 1985, Thatcher met Mikhail S. Gorbachev and passed the word that he was someone the West could deal with. As it turned out, she and Reagan clashed on the proper approach to the new Soviet leader. Thatcher wanted to negotiate under the NATO shield of nuclear weapons. Reagan aimed for something bigger: the abolition of all nuclear weapons.

Aldous notes that once negotiations began between Reagan and Gorbachev, Thatcher was largely frozen out. Refusing to give the Soviet Union any existing Western technology and using the concept of the Strategic Defense Initiative, the "Star Wars" strategy, Reagan forced Gorbachev to make concessions. Thatcher was angry, but when the Soviet Union split apart, she admitted that "the West won. Above all, Ronald Reagan won it." This view was shared by Polish leader Lech Walesa, who believed that Reagan had a vision of a world without communism. Reagan was no ostrich, Walesa later wrote, who hoped that communism would disappear of its own accord: "He thought that problems are there to be faced. This is exactly what he did."

Aldous' book is based on a thorough examination of recently declassified material, including Reagan's diary and important material from Thatcher's archive. He strives to make a great deal of the differences between Reagan and Thatcher, but in the end only seems to strengthen the image of the two forming a solid working relationship. The portrait of these powerful figures is well drawn and particularly gives the reader a new view of Reagan as a more effective leader than some have portrayed him in the past. In scholarship it supersedes other works on the Reagan-Thatcher relationship, although if one is looking for a broader overview, John O'Sullivan's The President, the Pope, and the Prime Minister: Three Who Changed the World remains the best portrait of the revolution that took place in the 1980s.

John Rossi is professor emeritus of history at La Salle University.