Why L.A.'s conductor hiring could reverberate in Phila.

A couple of weeks ago, the Los Angeles Philharmonic did something that will either prove foolishly impetuous or could pan out as one of the smartest and most decisive moves the orchestra industry has ever seen. With the competition for conductors of a certain level quite fierce, Los Angeles signed a 26-year-old as its next music director.

A couple of weeks ago, the Los Angeles Philharmonic did something that will either prove foolishly impetuous or could pan out as one of the smartest and most decisive moves the orchestra industry has ever seen. With the competition for conductors of a certain level quite fierce, Los Angeles signed a 26-year-old as its next music director.

In a world that still looks to father figures, that likes to spread the myth that musical wisdom comes inexplicably upon a podium personality with a graying of the temples, one of the country's major orchestras went out and hired a boy.

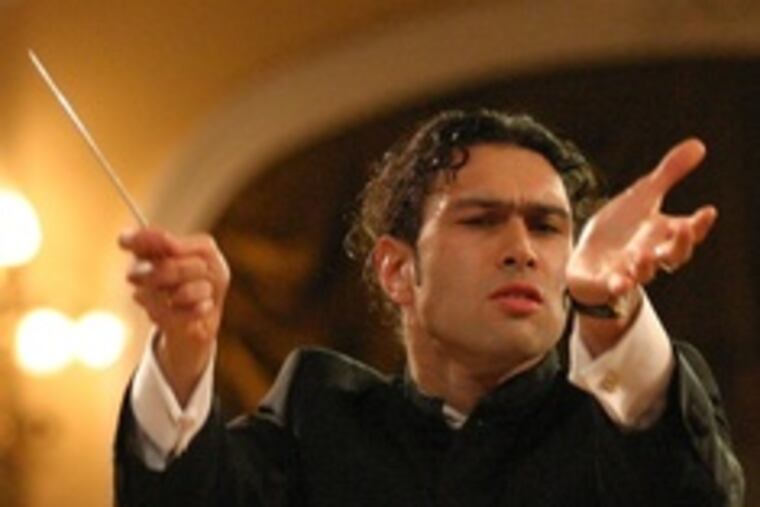

But let's not engage in ageism. Assume for a moment that the reasons the philharmonic named Gustavo Dudamel to succeed Esa-Pekka Salonen were purely musical. Even then, the decision starts to look more and more like a colossal risk.

When it comes to evidence of his talent, skill, stylistic alacrity and rapport with the musicians, what the philharmonic has to go on is extremely thin. The Venezuelan conductor, it turns out, has amassed the following experience with his new ensemble:

On Sept. 13, 2005, he conducted his first concert with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The single program, at the Hollywood Bowl, featured Revueltas' La Noche de los Mayas and Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5.

On Jan. 4 and 6 of this year he led Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra, Kodaly's Dances of Galánta and Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 3 - a program repeated Jan. 5 without the Bartók.

And that's it.

The man to whom the Los Angeles Philharmonic has entrusted its musical future has conducted four concerts with the orchestra. The players of the philharmonic have explored a total of five composers with their new leader. No Brahms, no Beethoven. No Mozart, Sibelius, Mahler, Shostakovich or Mendelssohn. Entire swaths of virgin orchestral repertoire await this partnership.

The risk is striking, and, in a way, inspiring. Hiring a music director after two programs is a lot like getting married after a couple of dates. The relationship could grow into a grand success. Or one night in the not-too-distant future one or both parties will wonder what they could possibly have been thinking.

Why should Philadelphia follow what happens next in Los Angeles? It's not just because anyone who cares about the future of orchestras should be thinking about the curious relationship between the maestros (or maestras?) and the ensembles that have come to expect so much of them. It's also because the Philadelphia Orchestra is searching for a music director.

And despite the fact that its last gamble didn't turn out so well, the prospects are looking fairly bright right now.

One prospect, Vladimir Jurowski, was looking so bright recently that the Philadelphia Orchestra decided to slow things down a bit, buying time by putting the grandfatherly Charles Dutoit in charge for a while. Dutoit's a good choice. But after the meticulous caretaking of the Wolfgang Sawallisch decade, and the shaky hand of his successor, the orchestra must remind itself what it means to grow its ambitions - institutionally and musically.

It needs to honor its past, yes, by cultivating its special sound in certain repertoire, which Dutoit will surely do. But it needs something more than quoting Ormandy style. It must define itself beyond its history. It must find a future - new specialties, new ways of connecting fresh scores to an impatient public, new overtures to classical newbies.

Let's also be clear about some more recent history. Christoph Eschenbach might have been a gamble that did not pay off, but it's not because he was an unknown quantity. He had guest-conducted here often, and there was nothing in those appearances that spelled music director. He was hired despite his musical relationship with the orchestra, not in the absence of one.

That's quite different from Jurowski's history here, with (like Dudamel) two spectacular visits under his belt. He is one of the most insightful conductors I've heard, and his chemistry with the Philadelphians is clearly special. He's only 35 and says he needs time to learn more repertoire as his visits to Verizon Hall increase in coming years.

That's an idea we can respect. But there's an intermediate step to music director that Philadelphia and Jurowski should consider: principal guest conductor. It signals serious intentions, and is a safe way to deepen the level of interaction among the musicians, conductor and audience.

Jurowski's next (scheduled) return is a year from now, conducting Ligeti, Brahms and Richard Strauss. If at that point the orchestra doesn't take the opportunity to formalize its relationship with the conductor, it really will be taking a risk.

In Los Angeles they're hiring 26-year-old conductors. Think of how many other ensembles out there would love to get their hands on a seasoned 35-year-old.