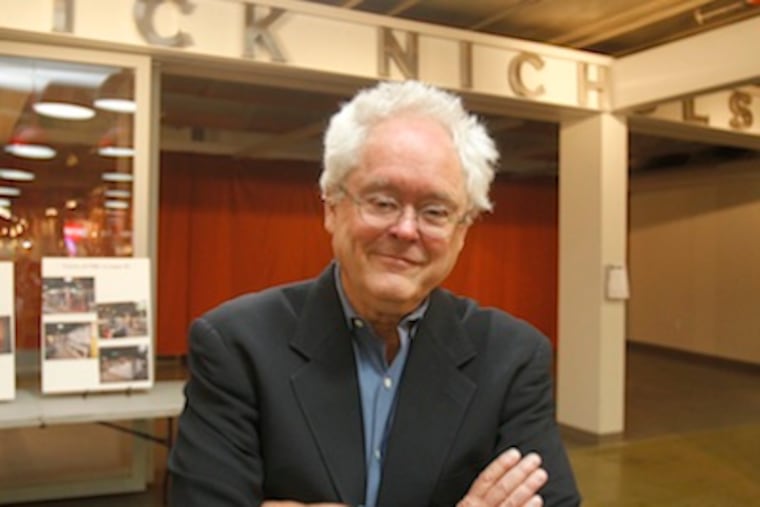

Reading Terminal remake, complete with Inquirer vet Rick Nichols' own room

Monday morning at the back end of Reading Terminal Market, Rick Nichols pinballed through a crowd of admirers, accepting and delivering hugs, kisses, and handshakes while an old-timey band oompahed and strummed.Nichols, who retired in 2011 after 33 years at The Inquirer, was being honored for his loyalty and love for the market, which he once helped save from nearly certain death. Behind him, brown curtains covered a yet-to-be revealed exhibit — a collection of photographs and text chronicling the market's 120-year history. And above the entrance, a string of big aluminum capital letters spelled out "Rick Nichols Room."

Monday morning at the back end of Reading Terminal Market, Rick Nichols pinballed through a crowd of admirers, accepting and delivering hugs, kisses, and handshakes while an old-timey band oompahed and strummed.

Nichols, who retired in 2011 after 33 years at The Inquirer, was being honored for his loyalty and love for the market, which he once helped save from nearly certain death.

Behind him, brown curtains covered a yet-to-be revealed exhibit — a collection of photographs and text chronicling the market's 120-year history. And above the entrance, a string of big aluminum capital letters spelled out "Rick Nichols Room."

The room, home to the new exhibit, will be used for small meetings and events and is part of a $3.6 million renovation project.

When Paul Steinke, the market's general manager, began his laudatory remarks, Nichols, looking both proud and embarrassed, stood off to the side of the audience, his hands jammed into the pockets of his black jeans.

But as a succession of speakers — city officials, the president of the market's merchant association, the CEO of the bank that lent the money for the renovation — echoed their appreciation of him, he sought refuge in seats nearer to his family: his wife, Nancy, a former Inquirer editor who now works at the Washington Post. His two sons, Eric and Coan. Three of his grandchildren.

When it was Nichols' turn to speak, he ambled up to the lectern, grinned, and said, "Hi!"

The market, he said, has been a place where he spent three decades "shopping and schmoozing." A place where "I feel I have a Reading Market family. Where ... I can go whether I am shaved or not, whether I have money in my pocket or not."

A handsomer version of Garrison Keillor, Nichols, 65, wears his white hair in an irreverent thatch. Blue-eyed and impish, his small, round facial features gather in a cluster. Leaning on the lectern, he explained that the new room is on the site of the market's old fish section.

"How appropriate to honor an antique journalist in a former fish shop," he deadpanned. "Because newspapers and fish have always had a natural affinity for each other."

Then he turned to Steinke and thanked him for making sure "that this honor hasn't been conferred posthumously."

During the 90-minute ceremony, the market's usual hum picked up volume. Sara Meyers, a 19-year-old from Roxborough working the counter at Molly Molloy's (one of four new food vendors that will occupy the renovated space near Rick's room) breakfasted on lo mein from a nearby stall.

Lines began to form for the pork sandwiches at DiNic's.

Grateful visitors streamed into the gleaming new restrooms that have replaced the woefully insufficient old ones.

At the ceremony, Edwina Hild took a front-row seat and sang along with the band's rendition of "Sweet Georgia Brown."

Hearing that the mayor was to speak at the event, Hild, 89, had traveled into Center City, with no small effort, riding buses from her retirement home in Wynnefield. (The mayor bowed out at the last minute and sent his deputy, Alan Greenberger.)

"I miss Philadelphia," Hild said. "There's no city like it." Especially the market, she said, with all its buzz and bustle, crowds and color, and the Bassett's chocolate ice cream, which she used to bring home — packed in ice — when she was in her 20s.

Watching Hild sitting by herself, singing, Nichols' grandchildren were moved. They were beginning to understand the market's magic.

"It's amazing," said Sebastian Nichols, 13. "Having a room dedicated to my grandfather. How hard he must have worked. Usually, he's proud of me at concerts and soccer games. Now I can be proud of him."