Eco-anxiety: Something else to worry about

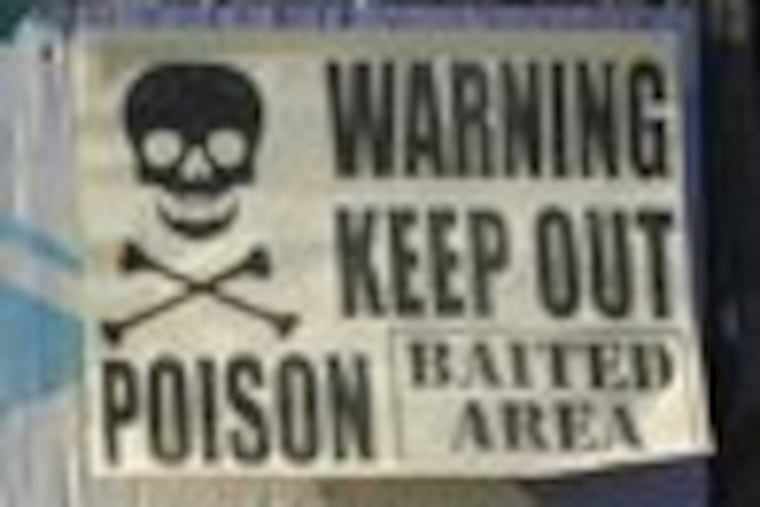

NEW YORK - Theo Colborn is renowned for her research on endocrine disrupters - tiny, mostly manufactured chemicals found in pesticides like DDT as well as everyday objects like plastic water bottles. She believes they are behind the rise in autism, ADHD, and some birth defects.

NEW YORK - Theo Colborn is renowned for her research on endocrine disrupters - tiny, mostly manufactured chemicals found in pesticides like DDT as well as everyday objects like plastic water bottles. She believes they are behind the rise in autism, ADHD, and some birth defects.

"This is a pandemic," she says. "Something is happening, and these systems aren't functioning properly."

Concerns generated by her own research led Colborn, 80, to make lifestyle changes. The environmental health analyst and co-author of the 1996 book Our Stolen Future avoids Tupperware and Saran Wrap; leftovers go in mason jars and empty peanut butter containers. In 1987, fearing a coming energy crisis, she bought a 900-square-foot cottage, no air-conditioning, within walking distance of the small town of Paonia, Colo.

While scientists like Colborn are making environmentally sound lifestyle choices based on their own study, a growing number of people have literally worried themselves sick over a range of doomsday scenarios.

Their worry has a name: eco-anxiety.

And the latest report on climate change - a United Nations panel warned Friday of increased hunger, water shortages, massive floods, avalanches, and species extinctions in various parts of the world unless nations take major action - is not likely to help.

Melissa Pickett, an eco-therapist with a practice in Santa Fe, says she sees between 40 to 80 eco-anxious patients a month.

They complain of panic attacks, loss of appetite, irritability and unexplained bouts of weakness, sleeplessness and "buzzing," described as an eerie feeling that their cells are twitching. Pickett's remedies include telling patients to carry natural objects, like certain minerals, for a period of weeks. Making environmentally friendly lifestyle changes can also prove therapeutic, she says.

The fears of the eco-anxious are fueled by abundant media coverage of crises like global warming, collapsed fisheries and food shortages. A slew of eco-disaster movies are on Hollywood's drawing boards.

Is the end actually nigh? If anyone can answer that question it should be the scientists. But they don't always make the best spokespeople.

"Scientists are very bad at communicating with the public about risk," says Benny Peiser, a social anthropologist at John Moores University in Liverpool, England, who studies the effects of catastrophes on society. "Unfortunately, a lot of low probability risks are blown out of proportion."

Peiser used to worry that an asteroid half the length of a football field would explode over New York or London, as one did in Siberia in 1908, burning miles of forest to a crisp. And there are the 10-kilometer asteroids, like the one known as Minor Planet (7107) Peiser - named after Peiser himself because of his "particular research interest in neocatastrophism and its implications for human, societal and cultural evolution," according to a NASA Web site.

Were Minor Planet (7107) Peiser to hit earth, it would cause an "extinction-level event," wiping out most life on the planet.

Fortunately, Peiser says scientists now are much better at detecting these mega-asteroids, and his fears about smaller asteroids have also been allayed somewhat. Recent research suggests that explosions like the one over Siberia probably happen once every 1,000 years.

Some feared hazards may be manufactured out of whole cloth. Robert Hale, a marine scientist at William & Mary's Virginia Institute of Marine Science, who studies the effects of PCBs and pesticides on sea life, blames journalists for the public's misinformation and subsequent eco-anxiety.

Hale refers to a 1997 episode known as "Pfiesteria hysteria." He says many writers attributed a spate of human illnesses in Mid-Atlantic states to a flesh-eating microbe found in the Chesapeake based largely on one researcher's views.

Gavin Schmidt, who studies climate variability at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in Manhattan, is concerned about carbon dioxide emissions unnaturally warming the planet, but he hasn't succumbed to eco-anxiety. He attributes the rise in environmental angst to a naive public.

"The fact that people don't have a good grasp of how science thinking works," Schmidt says, "means they don't have a good grasp of what they should be skeptical about."

Schmidt cofounded the blog realclimate.org to correct misinformation on climate change.

"There's a scientific reason to be concerned and there's a scientific reason to push for action," he says, "but there's no scientific reason to despair."