For men, a saving surgery

Twenty-five years ago, Patrick C. Walsh devised a prostate-cancer operation that allowed patients to continue a normal life.

In 1982, the surgical cure for prostate cancer was considered worse than the disease.

Removing the prostate meant life-threatening bleeding, guaranteed impotence, and a 1 in 4 chance of incontinence. Men feared a life of sexual dysfunction, diapers, humiliation, isolation.

No wonder 93 percent of early-stage patients opted for less-debilitating radiation, even though it lacked today's power to wipe out the cancer.

The year 1982 was also when Patrick C. Walsh, the self-confident young director of Johns Hopkins University's Brady Urological Institute in Baltimore, sat down with Bob Hastings, a 53-year-old Cleveland economics professor who was reeling from a prostate-cancer diagnosis.

Hastings, now trim and agile at 78, remembers Walsh's thrilling words: "He said, with complete modesty, 'I can cure you.' I liked that. He said, 'I don't think you'll have any trouble with impotence.' I really liked that."

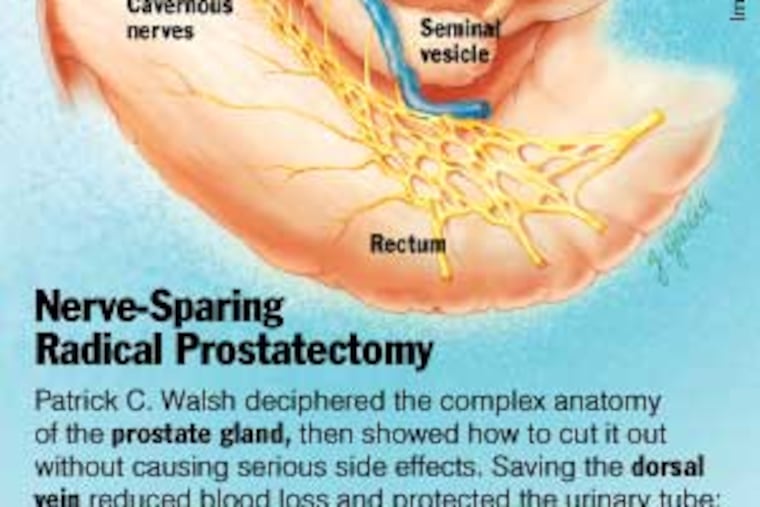

Walsh had made a fundamental but revolutionary discovery: vital blood vessels and nerves could be saved while cutting out the chestnut-sized organ.

On Wednesday, doctor and patient reunited to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Hastings' operation, the first-ever "nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy." More than 100 people gathered in the institute's elegant lobby for a seminar/cocktail party. Now 69, Walsh was hailed as "the Michelangelo of prostate surgery," a visionary whose work has "single-handedly changed the field."

Hyperbolic? Not by much.

Prostate cancer is still a dreadful disease, the most common cancer in American men. But thanks to Walsh's anatomic discoveries, dying from complications of nerve-sparing surgery today is almost unheard of, incontinence is rare, and sexual function is usually preserved.

Walsh's timing was right, too. With the advent of PSA prostate-cancer screening in the early 1990s, suddenly thousands of men were being diagnosed at a curable stage, before cancer had spread beyond the prostate.

"Clearly, the PSA test has helped us find the patients who can benefit from nerve-sparing surgery," said Richard Greenberg, chief of urologic oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center and a longtime friend of Walsh's.

It's hard to say how much nerve-sparing prostatectomy has contributed to the stunning 32 percent decline in U.S. prostate-cancer deaths since 1995, but Walsh believes the two are closely linked.

Last week's anniversary celebration wasn't completely reverential. Hastings, who flew in from Fort Myers, Fla., said he became Walsh's guinea pig because "one of my life's goals was to take an obscure surgeon and make him a great man."

Walsh, known for cracking bad jokes, loved it.

In June, Walsh will operate on his 4,000th prostatectomy patient. (Full disclosure: Inquirer editor Bill Marimow recently joined the growing multitude.)

Walsh boasts side-effect rates that only the best of the best can match: Less than 2 percent of his patients are incontinent, and 90 percent who are under 65 remain potent.

"God has been good to me," he says, sitting in his spacious, spotless office, where the coffee-table book is the Korean translation of Dr. Patrick Walsh's Guide to Surviving Prostate Cancer. "I'm at the top of my game."

A wiry guy who exudes energy, Walsh is simultaneously gracious and controlling (he moved Hastings' coffee cup so it wouldn't be in a photograph). The surgeon is quick with compliments - and condescension. He dismisses as "a jerk" an expert who questions whether early prostate-cancer detection and treatment really saves lives (a rancorous debate similar to that over mammography and breast cancer.)

Walsh also pooh-poohed the idea that surgeons performing "robotic" prostatectomy - a new remote-controlled operation touted as reducing scarring, blood loss and recovery time - have a better view inside the patient than he does.

More than anything, though, he is known for old-fashioned, unstinting devotion to his patients. He gives his home phone number to all of them, not just VIP patients like Sen. John F. Kerry. He spends three hours every Monday taking calls - five minutes per patient - from those less than three months beyond surgery.

"It's amazing because you really talk directly to him," said a 2005 patient, the Rev. Robert Childs, 51, a Baptist minister from Washington, D.C.

Walsh grew up in a Catholic family in Akron, Ohio, where his father owned a cigar store. Walsh always wanted to be a doctor - he has a photo of himself, age 4, wearing a white smock and toy stethoscope under the Christmas tree.

As he tells it, his dreams came true because he was "given" remarkable opportunities, starting with a scholarship to Case Western Reserve Medical School.

Others say he rose on genius and drive. Even now, at 69, he strives for ever-better outcomes.

"One summer, he spent weeks going over videos of his operations to see if he could identify the 2 percent of patients who wound up having incontinence and figure out why," said Janet Farrar Worthington, a science writer and coauthor of his consumer books. "Sure enough, he found a slight anatomic variation in some men and changed his surgery accordingly."

By the 1980s, scientists were transplanting hearts and cloning DNA. Incredibly, they still hadn't found the nerves that controlled an erection.

One problem was that the tiny webs of blood vessels, nerves and muscles surrounding the prostate were hidden under the fascia, a thick band of fibrous tissue.

Another problem was the adult cadavers used to teach anatomy to medical students. The process of preserving the bodies squashed the pelvic organs into what Walsh called "a pancake of tissue."

And there may have been a less obvious reason. Urologists had little incentive to develop a kinder, gentler prostatectomy because most patients' cancers were far too advanced for surgery. An operation cannot kill cancer that has spread beyond the prostate.

"We didn't have screening and early detection. We didn't have CAT scans or ultrasound imaging," recalled Greenberg at Fox Chase.

No matter. Soon after he arrived to lead Hopkins' Brady Institute in 1974, Walsh set out to decipher the anatomy of the gland that helps produce seminal fluid.

It took three years of using his surgical patients as "an anatomy laboratory," but Walsh finally identified the dorsal vein. Sparing it prevented excessive bleeding and - to his surprise - improved continence because nearby urinary muscles were also preserved.

The search for the erectile nerves took four more years. Most urologists believed the nerves ran through the prostate, and thus couldn't be saved. But Walsh was unconvinced because a Philadelphia patient of his had reported a seeming miracle: he was having intercourse less than a year after surgery.

In 1981, Walsh worked with Dutch urologist Pieter Donker on an infant cadaver. The organs were tiny, but not squashed. After hours of exquisitely careful dissection, they pinpointed the cavernous nerves - bundles running like a hammock on each side of the prostate.

"I was absolutely ecstatic," Walsh says. "It was like finding a new planet."

After Hastings' 1982 surgery, Walsh presented a paper on his techniques at a conference.

The phones at his institute began ringing incessantly. Administrative assistant Cynthia DiFerdinando remembers the secretaries' bewildered responses:

"Nerve-sparing? What nerves? Are you sure you want urology? You must want neurology."

Urologist Judd Moul, director of Duke University's Prostate Center, said, "It was a seminal discovery. I'm in the generation behind Walsh that really benefited from his work. I've based a majority of my career on the foundation he laid."

Researchers studying the biology and genetics of prostate cancer have also benefited because the popularity of nerve-sparing surgery has increased the supply of tumor samples.

Still, the advent of nerve preservation has not been without controversy. As late as 1994, Walsh had to defend his operation against unfounded criticism that leaving the nerves intact increased the chance of relapse.

He is the first to say the operation is difficult and takes years of practice. That's why he spends much of his time training young surgeons around the world and giving out free copies of his 90-minute instructional DVD.

He has no plans to retire. "I've been given a gift," he says.

Peggy, his beloved wife of 43 years, understands. They have three grown children and six grandchildren.

"I'd like him to do something else, but he's absolutely dedicated to this," she says. "The hardest part will come when he can no longer care for patients, because that's his first love."