Anatomy's graveyard

More than 1,000 bodies found at a construction site in West Philadelphia tell a story about science, medicine and society in the 1800s.

When construction workers digging out a parking garage hit human remains at University Avenue and Civic Center Boulevard, forensic anthropologist Thomas Crist was called in to investigate.

The 2001 discovery eventually yielded remains of more than 1,000 people, but only 400 of them lay in coffins. The sawed-off arms and legs of hundreds more lay discarded in 138 decayed scrap wood boxes.

He and 35 archaeologists dug them up and Crist and his wife, Molly, spent five years cleaning and scrutinizing the bones and fragments. What came from all that was a little-told story of 19th century Philadelphia - where the lives of those people laid low by poverty, epidemic disease, alcoholism or mental illness intersected with those of the medical superstars who used the bodies to rewrite anatomy textbooks.

At first, Crist thought the bones might be connected to the nearby Woodlawn Cemetery. Then members of his team went digging through the city's archives and libraries.

Eventually one of them found an old map that matched their site to a burial ground associated with the Blockley Almshouse, which housed the city's poorest citizens through much of the 19th century.

"People were terrified of ending up in Blockley," said Crist, partly because they feared what would happen after they died.

Today, a parking lot occupies the old burial ground, and Crist and his colleagues have finally finished their work. They presented their findings earlier this spring at a meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists in Philadelphia.

"What you have is like a series of snapshots of the lowest echelon of Philadelphia society," said Gary Nash, a University of California historian and author of The First City, Philadelphia and the Forging of Historical Memory.

Blockley was the third Philadelphia almshouse. The first two operated in the 1700s. By 1834, said Crist, city officials wanted to move the sick and poor out of Center City, so they built the new one in an area known as Blockley across the Schuylkill River.

The more than 1,000 people held at Blockley were called inmates - not residents. Between the 1830s and 1890s, the stately building imprisoned the city's unwed mothers, alcoholics, syphilis patients and others who ran out of money, friends, family and luck.

Henry Bliss, a Blockley doctor in 1883-84, described some of his patients in Blockley Days, a book published three decades later. There was a delusional old woman, a sweet and personable 16-year-old boy with a massive and deadly tumor on his neck, and a cranky old alcoholic, unsteady and red-nosed, who had once held a professorship at England's Exeter College.

"It was a sort of microcosmos, representing the misery and goodness, the meanness, the brave endurance, the cheap deceits, the vileness and degradation of the whole great world," wrote Bliss.

He describes one career criminal, called Edmunds, who died at the almshouse, as "a strange combination of "meanness, wickedness, low cunning and moral cussedness."

Edmunds apparently died from complications after doctors tried to operate on his hip. Bliss sat with him overnight, expecting him to recover. But the next day he took Edmunds to the "green-room" - where he and another doctor dissected him.

From Crist's analysis, many others suffered a similar fate, at the hands of not only Blockley doctors but visitors from the University of Pennsylvania Hospital and Jefferson Medical College, now Thomas Jefferson University.

Back then, said Crist, these people had no rights over their bodies. "If you were being put up in the almshouse, society assumed the least you could do was make your body useful."

Soon after Crist and his team finished excavating the thousands of bones, he and his wife moved them to Upstate New York, after both secured job offers at Utica College.

Today the bones are crammed in the basement of a building on the edge of the small campus. Several hundred cardboard boxes the size of milk crates line the walls, filled with what Crist says doctors threw out as "medical waste," and "surgical specimens."

Crist picked up a backbone from a table, pointing to the way the disks were fused. "This gentleman would have had trouble bending over," he said. Another backbone was so severely curved it was hard to imagine how its owner got around.

He demonstrated how the pubic bone and tailbone can reveal an approximate age, since parts of them tend to break down and regrow in a telltale way over the years. The most contorted backbones came from people in only their 40s and 50s.

"These people lived an incredibly harsh life," he said.

There were ruined hips - the sockets worn rough. There were bones made porous as pumice from osteoporosis, fused foot-bones, stiffened knees, and bones ragged at the edges - a sign of severe arthritis.

These were dockworkers and washerwomen who did backbreaking work without getting proper nutrition, he said.

One nearly complete skeleton lay flat on another table - a man, Crist said, between 40 and 45, who died from syphilis. "Look how the joints are swollen," he said, pointing out the distorted limbs. "That's inflammation that comes when the infection goes into the bone."

Some of these remains may end up in the Mutter Museum, he said, and some may be buried in a cemetery.

The Catholic Church started allowing dissections in the 1600s, and by the 1700s medical schools started to use them as a staple of teaching, first in Europe and later in the American colonies.

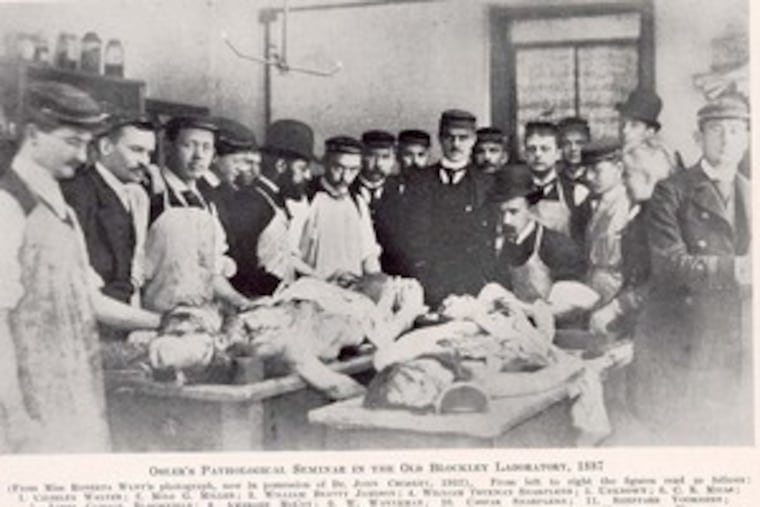

That allowed doctors to create the first accurate anatomy textbooks in the 18th and 19th centuries. There was a tremendous enthusiasm for anatomy and the dissection of the human body, said Michael Sappol, a medical historian at the National Library of Medicine and author of A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. "It was considered the most scientific part of the medical curriculum and part of the mystique of medicine," he said, similar to how the human genome is regarded today.

Bliss, the 19th-century almshouse doctor, wrote in his journal that the dissections helped doctors improve their diagnostic powers, since even the most acclaimed doctors often got it wrong. ". . . the observations held in this room may prove that the professor's bad organs were good organs, and that good were all bad."

Members of the general public wanted to go to doctors who had dissection experience, he said, "but they didn't want to be dissected themselves." And because few were willing to donate their bodies, doctors got them from the least powerful members of society.

At one point, Sappol said, the residents of the almshouse protested to its board of managers, claiming the doctors were "circling them like vultures," waiting to turn them into cadavers. At that time, using almshouse residents was quasi-legal, he said, and after 1867, Pennsylvania law allowed doctors to use the bodies of deceased almshouse inmates without consent.

Many of the doctors who studied those bodies became famous - William Osler, Caspar Wistar, and Elizabeth Blackwell, the nation's first woman to earn a medical degree.

Back in Utica, students still use cadavers to learn anatomy much as they did two centuries ago. In a cramped lower-floor laboratory, 20 or so students, mostly young women, recently poked, prodded and examined four corpses as they prepared for an anatomy exam. The skin had already been removed, the ligaments and muscles exposed.

There's no substitute for working with cadavers, said Molly Crist, to help students learn the human body, whether they become doctors or physical therapists.

Most medical schools conduct a non-denominational ceremony to recognize the people who donate their bodies, said Tom Crist, and most cadavers used in anatomy courses are cremated, with their ashes either buried or returned to their families.

But the supply remains as short as it was back in the days of Blockley. Several years ago a scandal broke out after the discovery that illegal "body brokers" procured parts from funeral homes for tissue replacement and surgery practice. The demand is high - a cadaver or even just parts can bring in more than $1,000.

After a tour of the semi-dissected bodies, Tom Crist took the lid off a plastic bucket tucked in a corner. He leaned in to pick out a disembodied foot - then a shoulder, showing the intricate series of tendons and ligaments.

This, he said, is the modern equivalent of the work that went on in the 1800s and resulted in those parts buried in West Philadelphia. The specimens dry out, or they decide to replace them, he said. "They can't just dump them in the river."

"There was a huge dichotomy," he said as he put away the parts. It may seem barbaric to us to dissect bodies of unconsenting people. "The doctors did things simply because they could," he said. "And yet at the same time they were trying to save humanity."