For abusive men who want to mend their ways

Once the men can admit they havea mean streak, they face a tough 20-week program at Menergy, a counseling program for abusers.

The birthday cake was the last straw. Michael, 35, enraged when he saw the four-layer extravaganza on his dining room table, muttered a curse and smashed it into a heap of pink and white crumbs.

He had wanted to buy that cake for his daughter's fifth birthday, but, now, here it was, ordered and paid for by his wife's parents.

"I went berserk," he recalls.

Three days later, at his wife's insistence, Michael called Menergy, a private counseling program for abusive men. Sixty percent of the men who come to Menergy are referred by the courts because they have been physically violent. Most of the rest are emotional abusers who come on their own, usually because they have lost or are at risk of losing significant relationships. Most stay for about 20 weeks; some participate for two years or more.

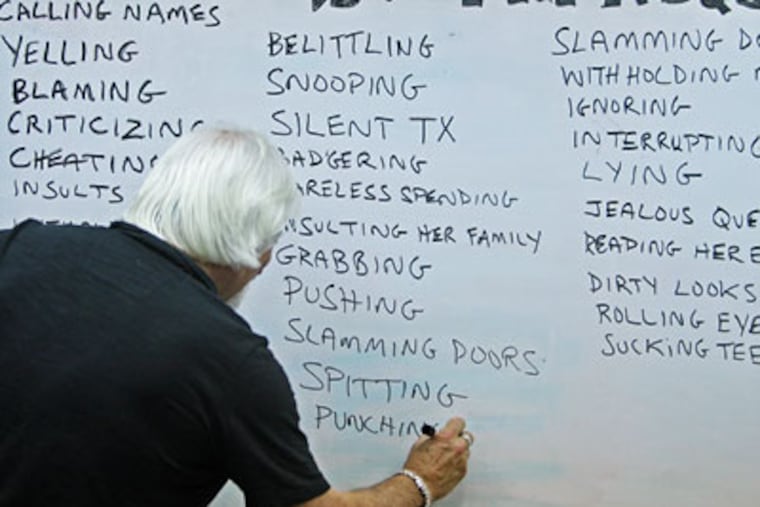

On a recent evening, eight men, sitting in a semicircle in the basement of a former school for the deaf, were asked to define emotional abuse. As quickly as the men shouted out the words, Tony Lapp, the program's assistant director, scribbled them on a board.

Screaming! Blaming! Criticizing! Withholding sex! Cheating! Putting down her family! Insulting her friends! Cursing! Controlling! Interrogating! Ignoring! Belittling! Reading her e-mail! Giving her the silent treatment!

In 10 minutes, the board was jammed. The group's newest member piped up: "I think all you guys talked to my wife before you came here tonight." Everyone laughed.

The men agreed to be observed in their groups and to talk to a reporter provided their names were not used. They say they are ashamed of their behaviors, which, often, are known only to their wives or partners.

Menergy is Philadelphia's oldest counseling program for abusive men and one of the oldest in the country, celebrating its 15th anniversary tomorrow. Its founder, Paul Bukovec, a substantial, sturdy-looking man with white, near-shoulder-length hair, and a demeanor that suggests he is not one to coddle his clients, makes an impression on the men who have been through his program. "He can see right through you," says George, 38, who is just completing his 20th week at Menergy. "He doesn't let you get away with anything."

George had been married for two years when he went for his first interview with Bukovec. During most of his marriage, he admits, he screamed at his wife, cursed her, and insulted her because she had given up her job as an interior decorator and wasn't working.

But it wasn't until he knocked down the door to their bedroom during a fight that he realized he had an oversize problem with rage and anger. He found Menergy on the Internet. "It's the best thing I've ever done," he says.

It isn't easy to enroll in Bukovec's program. The men must go through a grueling three-session, face-to-face evaluation, which includes an embarrassing exercise during which each man must role-play his wife.

Bukovec fires a series of questions about his behavior toward her. For instance, he asked George (playing his wife): Does he ever call you names? What names? How do you feel being called names like that? Would it be fair to say he has a mean streak when he's upset?

"Once a man has acknowledged he has a mean streak, it is easier to get to him," Bukovec says, with a conspiratorial smile. "It is an elegant little thing. We learn a lot in a half hour. By the end, he is a limp dishrag."

And it isn't over yet. There is the 13-page background-history form with 84 criteria of abuse on which the men must rate themselves and how often they've done the following: express intense jealousy, harass at work site, ridicule, stare at threateningly, interrupt when partner speaks, slam doors, throw objects, spit on, to name a few. If they don't fill it in, they won't be accepted.

"There are some self-absorbed, middle-class, professional types who think they're special," says Bukovec. "We are kind, but we are rough, and the men, whether they're doctors, ministers or plumbers, have to walk a line. We make the rules, set limits, and expect the guys to step up."

Menergy, too, has been evaluated. Studies by the University of Pennsylvania in the late 1980s and early '90s found that one year after completing the program, 69 percent of the men - both physical and emotional abusers - had not relapsed. That figure fell to 59 percent a year later.

These findings are similar to those in an extensive 2001 study of four other sites, sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bukovec, 63, knows his clients well because he can identify with their behaviors. He was raised in a blue-collar, working-class family with a father who was explosive, smacked him around, and was incredibly moody - not an ideal role model. "My mama told me I wasn't like him," says Bukovec, "but when I grew up, I learned I was a lot like him. On occasion, I was verbally and emotionally abusive, so I had to work very hard to be different from the man who raised me. Consequently, I'm rather good at understanding the basic reasons behind emotional abuse, getting the men to see their patterns, and getting around their defenses." Bukovec believes that most people are abusive at some level and need to recognize and stop themselves when they start to cross the line.

"The first time I walked into a group, it was a little bit of a scary environment," says Barry, 52. "Here I am, an educated physician, and I'm sitting next to a guy who dropped out of high school in ninth grade and pulled a gun on his wife. It is an adjustment to realize I'm no better than he is. It was uncomfortable . . . and it should be."

Barry's abuses were, he says, "a whole grab bag of things: slamming doors, talking down to my wife, withdrawing from her, sulking, acting resentful when I felt misunderstood."

As each man in his group told his story, Barry glimpsed parts of himself and says he felt "so ashamed." When he described what he thought was a fairly good week, marred only by yelling at his wife for keeping him waiting at a restaurant, his peers responded with what he calls "the therapeutic slap."

"It isn't just Paul who kicks our a-," Barry says. "The others are the first ones to hold your feet to the fire. You can't get away with much. But this is a safe place where you can 'fess up. You tell each other your darkest secrets."

Before coming to Menergy, Barry would never have classified his behavior toward his wife as abusive. In his mind, abuse was something physical: hitting, choking, grabbing. Something you read about in the papers or saw on TV. All he did was raise his voice, insult, sulk, criticize, and shut down. "I thought I was justified," Barry says, "that I was the victim."

It wasn't until his wife gave him an ultimatum - figure out what's wrong with you, or leave - that he thought, "Maybe I am the problem."

There are no statistics quantifying emotional abuse. But SaraKay Smullens, a family therapist and domestic-violence activist, says it is epidemic in all socioeconomic groups. The bruises don't show as they do when someone is hit or choked. But the recipients can be psychologically destroyed. "When you live in a constant state of humiliation, you lose your self-esteem, feel diminished and worthless," Smullens says. "Depression sets in. There is often a desperate attempt to hide the source of your pain from friends and relatives, because you are so ashamed."

The most direct route to emotional abuse is to witness it, which can be more powerful than being its recipient, says Bukovec. "Children are like sponges and pick up abusive patterns. They may learn that it's OK to vent frustrations harshly at home with the people who are close to you, but not in the workplace, because the consequences could be too severe. If Dad screams or scolds and Mom accepts it, a child when he grows up may expect that his partner will do the same."

At the root of abuse is usually anger. Current actions trigger old-style reactions; something today's partner does or says resurrects the frustrating or hurtful things that happened long ago. Over the years, unless there is intervention, the cycles of emotional abuse grow and slide from generation to generation.

George's wife, Lily, says her life before her husband went to Menergy was a nightmare. "No matter how much he yelled or lied or stormed out of the house, I was afraid to say anything," she admits. "I didn't want to make him upset, because I wasn't sure of his reaction. I would just leave the room or try to calm him down. I lost my best friend because I wouldn't leave George, and finally, I decided I couldn't live that way anymore."

Lily joined a counseling group for abused women; George found Paul Bukovec.

In the last several months, after nearly a year in the program, Lily has seen a startling change in her husband and says she can't believe the progress he has made. The screaming has stopped, there is no more stomping out of the house, and George no longer watches pornography instead of being intimate with her. "I'm surprised," says Lily. "For the first time, I think my marriage has a chance."

Facts on Menergy

SOURCE: Menergy

EndText