Penn archaeologist recreates ancient brews

Patrick McGovern had just emerged from the ancient burial chamber in one of the most extensively excavated archaeological sites in China when a local scientist presented him with what he calls "the real treasure." It was a sealed bronze drinking vessel that resembled a teapot from 1200 B.C. With liquid still inside.

Patrick McGovern had just emerged from the ancient burial chamber in one of the most extensively excavated archaeological sites in China when a local scientist presented him with what he calls "the real treasure."

It was a sealed bronze drinking vessel that resembled a teapot from 1200 B.C.

With liquid still inside.

"I just about dropped over - a liquid sample from 3,000 years ago," said McGovern, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania.

He whisked a sample back to his lab in the basement of Penn's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. An analysis confirmed what he had suspected: a yellowish wine.

It was another eureka moment for McGovern, 64, who has spent the last two decades traversing the globe, from ancient capitals to remote villages, in a quest to uncover the secrets of ancient wine- and beer-making.

He has become internationally recognized as an authority on ancient potables. When he and other museum researchers were on the budget chopping block earlier this year, nearly 4,000 supporters signed a petition, among them archaeologists, curators, and government officials from countries around the world. Egypt's director of antiquities was one of them.

"You find out who your friends are," said McGovern, whose job was spared.

This month, he released a book, Uncorking the Past, which describes his research, including his collaboration with Delaware beer brewer Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head to re-create ancient beverages with recipes he found.

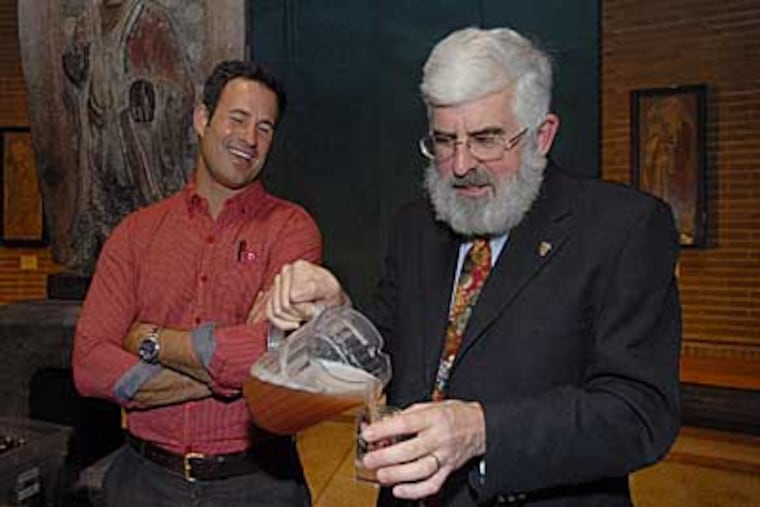

Last week, at an event at the University Museum, he and Calagione detailed their latest quirky foray: making an ancient Peruvian beer that required them to spend hours chewing purple corn - using their saliva as part of the fermentation process.

Two months ago, McGovern traveled to Lebanon's Bekaa Valley at the behest of a Syrian Lebanese winemaker who wants to open a wine museum there. He'll be heading back this month for further consultation.

"My husband loves what he does," McGovern's wife, Doris, said during an interview in the couple's woodsy Media home, where a wine magazine and a beer book sat atop a reading table. "It's a consuming passion."

His first experience with potables came on a student bicycle tour through the German Alps when he was 16. He drank Coca-Cola until he discovered beer was cheaper.

When he returned home to Upstate New York, he wanted more beer. So he dressed in lederhosen and a green hat, went to a bar and, pretending to be foreign, asked for a beer in German. He got it.

His first acquaintance with wine came in 1971 as he and his wife backpacked around Europe with little money. They visited towns along the Mosel River in Germany, seeking work at vineyards. The couple landed a three-week gig in Trittenheim.

"That's where I really got the whole notion of vintage worked out," McGovern said. "By the end, you knew 1959 was a superb year. Sixty-nine was awful. The year we worked there - 1971 - was like the vintage of the century."

Born in Texas, McGovern - the son of an engineer and teacher - grew up in New York, earned a degree in chemistry from Cornell University, and considered becoming a neuroscientist. But his interest turned to archaeology, and in 1977, he began working at Penn, where he got his doctorate in 1980.

"I was really wondering what man's place in the universe was, how we got here," he said.

It was, at times, a hard life. On research trips, he sometimes slept in buildings with no mattresses or heat.

He hasn't seen his face in 35 years. He gave up shaving after trips to spots lacking much hot water; his bushy beard and mustache have gone from black to white.

McGovern and his wife, an academic turned bird-bander whom he met as an undergraduate at Cornell, never had children or pets; that would have hindered their extensive traveling, he explained.

Over time, McGovern became interested in ancient pottery, then discovering what was inside the pottery.

A colleague presented him with a large jar from Iran from 3500 B.C. that had a reddish deposit. She sought his analysis. The vessel contained tartaric acid, a key ingredient found in grapes from the Middle East.

"That started us off on the wine odyssey," he recalled.

In 1999, McGovern began studying residue collected from drinking and eating vessels that were excavated in 1957 from what was believed to be King Midas' tomb in the ancient Turkish city of Gordion. There, researchers had found the largest Iron Age bronze drinking set to date.

The samples, brought back to the museum by Penn researchers, sat largely untouched until another researcher told McGovern.

One was the residue of a spicy, barbecued lamb or goat stew with lentils. Another was a drink with grape wine, barley beer, and honey mead. McGovern decided to re-create the dinner that the ancients must have had, but he needed beverage help.

After a beer-tasting at the museum in 2000, he invited 15 local brewers into his lab and issued a challenge: Here's an ancient recipe. Brew it. Whoever does the best will make the drink for a forthcoming dinner.

One of the brewers was Calagione.

"I was immediately struck by his passion," Calagione said. "It wasn't just a pedantic academic suit. He, like me, is truly passionate about the history and the romance of the stories behind these beverages."

Calagione added saffron to his brew; other brewers used coriander. McGovern preferred Calagione's version.

"Midas Touch" - the first brew the pair collaborated on - was served. It was 9 percent alcohol.

Later, Calagione and McGovern re-created the dinner at the tomb site in Gordion, with locals dressed in period costumes taking part.

After McGovern made a trip to China, the pair next collaborated on Chateau Jiahu, a re-creation of the oldest confirmed alcoholic beverage in the world, dating to 7000 B.C. Named after the ancient city of Jiahu, it contained hawthorn fruit, rice, and honey.

That brew won a gold medal at the Great American Beer Festival last month in Denver. Calagione invited McGovern - whom he calls "Dr. Pat" - to accompany him to the dais and accept the medal. He gave it to McGovern to keep.

Dogfish donates part of the proceeds from the re-created ancient beverages to McGovern's research, in recognition of his contribution. Most of the brews are available commercially from Dogfish.

The pair collaborated next on Theobroma, a chocolate-based ale from Central America. McGovern obtained the recipe from Honduras.

Last summer, they re-created their fourth ancient beer, the Peruvian Chicha, after McGovern made a trip to Peru earlier in the year. Colleague Clark Erickson, a Penn anthropology professor, joined McGovern and Calagione at the Rehoboth Beach, Del., brewery last summer to help chew the corn - saliva turns the corn into sugar - and make the concoction.

Both Erickson and McGovern wince when thinking of the six hours spent chewing brittle corn.

"The following day, your jaw is sore," McGovern said.

But it was fun telling his 150 guests at the museum event about the raw research.

"It may not sound appetizing," he told his guests, assuring them that a boiling process and alcohol killed off bacteria. "And it may add some special flavors."

With dozens of beverages at the gathering to sample, the line for Chicha was one of the longest.

McGovern, meanwhile, said he preferred the powerful flavor of Chateau Jiahu as he ruminated on the larger significance of his passion, which has crossed continents and time.

"It has contributed to how culture around the Earth has developed," he said of his research.

Four Ancient Beers

Midas Touch: Made with white grapes, saffron, thyme, honey, and barley from a recipe from King Midas' tomb in central Turkey. Alcohol: 9 percent.

Chateau Jiahu: The oldest confirmed fermented beverage, from a recipe found in China, made with yeast, rice, honey, and hawthorn fruit.

Alcohol: 10 percent.

Theobroma: From Central America, made with cocoa powder, honey, chiles, and annatto seeds.

Alcohol: 9 percent.

Chicha: From Peru, made with organic purple corn, pepper tree seeds, and strawberries. Alcohol: 6 percent.

SOURCE: Dogfish Head and Patrick McGovern

EndText