Despite success, demand low for hand transplants

A year after a young amputee left the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania with transplanted hands and forearms, the lead surgeon calls her progress "nothing less than spectacular."

A year after a young amputee left the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania with transplanted hands and forearms, the lead surgeon calls her progress "nothing less than spectacular."

Yet Penn has no waiting list for hand transplants.

The distinguished medical center is part of an ironic trend: Availability of the complex reconstructive surgery has been growing faster than demand for it.

Of perhaps two dozen hand transplant programs worldwide, 10 are in the United States. Two years after launching, two of the American centers have done no transplants. Five, including Penn, have each had one patient.

Even the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center - the country's second-oldest, second-busiest program - has had just five patients since its first surgery, in 2009.

"There are many issues, including funding and patient selection," said Joseph E. Losee, Pitt's director of reconstructive transplantation. "That's why you're not seeing that many being done."

The biggest issue, by all accounts, is the one that has been controversial from the start. Hands are not lifesaving, yet patients must take immune-suppressing drugs for the rest of their lives to prevent transplant rejection, just like recipients of vital organs. The drugs put them at risk of tumors, infection, diabetes, hypertension, and premature death.

"The risks of immunosuppression have to be weighed against the benefits" of improved quality of life, said Brian Carlsen, surgical codirector of the Mayo Clinic hand transplant program, which has not yet had a patient.

Researchers are avidly trying to get the body to tolerate transplants with less medication. Achieving this could open the door to replacing many nonessential body parts, from thumbs to wombs.

Meanwhile, hand transplant candidates must undergo rigorous psychosocial testing designed to weed out those who are not up to a transplant lifestyle, including being vigilant for hand swelling or other indications of trouble.

"If there is any sign of rejection, they have to come to the hospital. It doesn't matter if you have a vacation planned or if you have a big test the next day," said Losee.

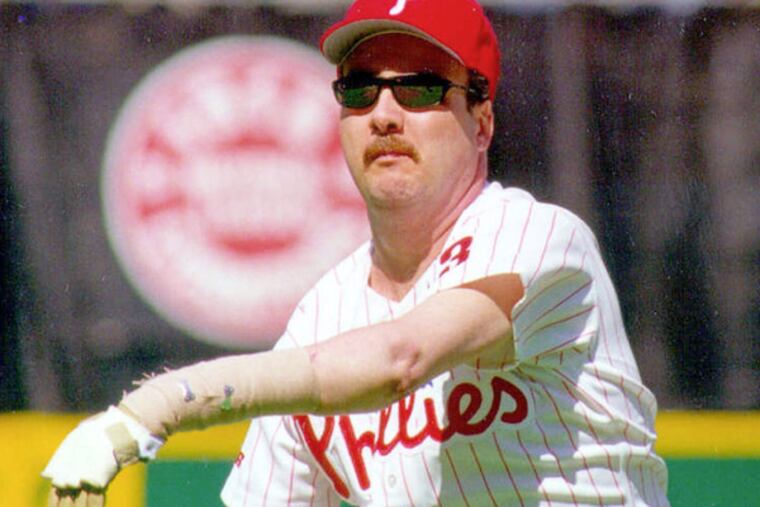

Matthew Scott has not found the medical regimen to be onerous. The Mays Landing, N.J., resident became the first U.S. hand transplant patient in 1999, when doctors in Kentucky replaced the appendage he had lost in a firecracker accident.

"I'm 13 years out and, to be honest, I've been just fine," said Scott, 51, paramedic trainer for Virtua Health. "I don't live my life that much differently than before the transplant."

Although only about 80 people worldwide have received hands since the first successful operation in France in 1998, outcomes have been reassuringly good. Studies show that a year after surgery, 96 percent of grafts survive - better than any other field of transplantation.

Most of the 19 U.S. patients reportedly have regained significant function and sensation - albeit with lots of physical rehabilitation.

Penn's patient, Lindsay Ess, 29, of Richmond, Va., lost her lower legs and lower arms to a bloodstream infection. She declined to be interviewed, but lead surgeon L. Scott Levin described her outcome so far as "almost miraculous."

"She's now living independently," Levin said. "She can take off her lower extremity prostheses with her hands. She's tolerating her medications extremely well."

Obtaining limbs from deceased donors also has turned out to be easier than anticipated.

"We thought we'd have people lining up and no raw materials," Pitt's Losee said. "For us, at least, donors aren't the problem."

While immune suppression is the primary obstacle, a close second is money. Because hand transplants are elective and still considered experimental, they are not covered by most health insurance. (Insurers do cover the immune drugs.)

The Kentucky program, which involves the University of Louisville and Jewish Hospital, has used research grants from the Department of Defense to subsidize the care of its eight patients, said surgeon Joseph Kutz. He estimated hospital costs at $225,000 per patient.

Given the high hurdles and low demand, why have hand graft programs proliferated in the U.S.? Some say it's because premier institutions want to offer premier treatments.

"It's a good question," said Carlsen at Mayo. "All I can say is, when we started, we felt there was patient need. And we felt the time was right and that, being who we are, we should be able to offer this treatment option."

at 215-854-2720 or mmccullough@phillynews.com.