A new play explores girls and aggression

NORTH PHILA. Doug Wager, artistic director of Temple University's theater program, plunged into books about the hidden, heartbreaking life of girls after he saw what happened to his 13-year-old daughter two years ago. Mean Facebook comments turned a sweet bar mitzvah dance into one of those awful memories that women never seem to forget.

NORTH PHILA. Doug Wager, artistic director of Temple University's theater program, plunged into books about the hidden, heartbreaking life of girls after he saw what happened to his 13-year-old daughter two years ago. Mean Facebook comments turned a sweet bar mitzvah dance into one of those awful memories that women never seem to forget.

His daughter now downplays how the girls who mocked her made her feel, but Wager hasn't let it go. He is 64, and Miranda is his only child. He feels protective and inadequate and frightened for both of them. How can he help without making it worse?

As he read about bullying, he realized that Miranda had shown him the surface of a deep lake. Boys might duke it out on the playground, the experts said, but girls often do their hurting with vicious words the teacher can't hear, with exclusion, rolled eyes, and whispers. In their world, an ellipsis in a tweet - a sign of unspoken conflict - is cause for alarm.

Then Wager did what he does to cope, to feel, to expose injustice and, maybe, to become a better father.

He made a play.

"It is my way of expressing my feeling about the world that I'm putting my daughter into, or the world that she lives in," he said.

"It's hard to express how deeply you love a child. Now I'm getting all teary-eyed."

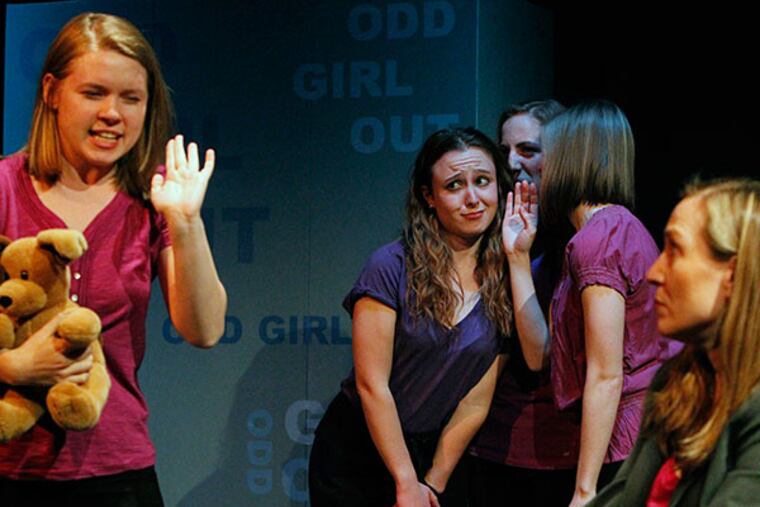

His new work, Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls, premieres Wednesday at Temple. The adaptation of the 2002 book by Rachel Simmons also includes verbatim material from interviews done by the all-female cast and students in one of Wager's classes.

More than once during the play's creation, the students found memories triggered by interviews and acting exercises so disturbing that Wager had to sit them down for impromptu group therapy. Wager also found it the most personally emotional piece he had done in decades.

"It's what you strive for as an artist," he told theater majors at a class explaining how the play came together. "When do the head and the heart meet? . . . When are you healing yourself in the process of healing others?"

The play, which strings snippets of interviews into an "emotional narrative" interspersed with song, narration, and poetry, focuses on relational or psychological aggression, what Wager called the "weaponizing of friendship and intimate relationships." The theory is that the pressure to be "nice" is so intense that it makes girls express aggression in insidious ways.

This is different from bullying. Simmons describes that as "a protracted campaign of aggression against someone who has less power than you do."

Recent research, she said, has found that boys, too, experience "enormous anguish" from psychological aggression. "I somewhat regret my book in feminizing that behavior," she said. "I was, like, 24 when I wrote" it.

Wager knows the argument that this is just how girls are, that rejection and some abuse are part of growing up. "That's just not an acceptable answer," he said.

He came to this project with a long history of staging "docudramas" about complex topics such as the 1980s farm crisis, the Iraq war, and gun violence. He tries to expose audiences to all sides of an issue and let them make up their own minds. Odd Girl contains the voices of victims and aggressors.

One of the distressing lessons for the young actresses was realizing they could be both. "You talk behind their back because someone talked behind your back," said Anna Snapp, a junior from Silver Spring, Md.

Like most of the cast, she had memories she could draw on. A friend dropped her when she was going through a difficult time. "To this day, it hurts me," she said, "and it hurts me every day, and she has no idea it had this effect on me."

Wager sent his students, armed with questions suggested by Simmons, out to tape interviews of elementary school girls, teenagers, and women about their experiences.

Then he taught them a technique pioneered by the actress and playwright Anna Deavere Smith, with whom he worked at Washington's Arena Stage.

The actresses immersed themselves in the audio, listening first not for content but for breath, cadence, pitch, and accent. They listened in the shower, while running, while walking to class, until they could duplicate the voices of the interviewees. Everything would flow from that. The technique, Wager said, allows actors to tap into the physiology of emotion, the physical manifestations of character.

Anna Lou Hearn, a senior from Baltimore, noticed that her "character" was breathing oddly and that her voice would rise in pitch when she said, "Like it was all my fault, and like I was the one that was supposed to walk around being ashamed."

As she matched the breath and pitch, Hearn realized what was happening: "She's about to cry."

Eventually, the 13 actresses would add their own styles to heighten the drama.

The result is two-minute speeches that are full of half-finished sentences and immature ideas. They are not great literature, but they sound utterly authentic. The little Randall Theater aches with the tales of mysteriously fickle friends, hostile lunch rooms, corrosive jealousy, and an intense fear of conflict that makes lies and abandonment feel safer than the truth.

Simmons says some of this is inevitable. Relationship skills, which she now teaches, don't come naturally. We are both hurt and hurtful as we learn them.

She calls "toxic relationships" a powerful learning ground. Parents can't give their children a world free of hurt, but they can help. "The question is, 'Are we going to guide girls thoughtfully through that,' " Simmons said, "or are we going to pretend it's no big deal?"

Miranda Wager, now 15, decided against an interview for this story, fearing it might cause more trouble. But she did allow her father to use one of her poems, "Little Girl," in the play, and insisted that he put her name on it.

She is doing well, he said. "She made the choice that she wasn't willing to give up her own personal identity to try to fit in."

The poem, written when Miranda was 13 to her younger self, is about being taunted - called a "hippo" - on the school bus.

"Those who hurt you mean nothing," it says. "They have no value in your life. Let the words of hate guide you to a path of power and understanding."

The play will be performed April 23, April 25-27 and April 29-May 3 at Randall Theater on the Temple campus. Tickets: $20 General Admission, $15 Students/Seniors/Temple Employees, $5 Temple Students, plus applicable fees. For tickets: 215.204.1122 or templetheaters.ticketleap.com

215-854-4944 @StaceyABurling