Fentanyl is killing more Philadelphians than any other drug, medical examiner finds

By the Medical Examiner Office's tally, 1,217 people died of drug overdoses in Philadelphia last year - in line with what health officials had predicted as early as last fall.

As Philadelphia's drug overdose deaths spiked in 2017 to their highest point ever, fentanyl proved the most fatal of all drugs implicated in unintentional deaths, killing more people than all other opioids, including heroin, according to statistics released by the Medical Examiner's Office Tuesday.

By the official tally, 1,217 people died of drug overdoses in Philadelphia last year — in line with what health officials had predicted as early as last fall.

The medical examiner's report "really clarified that this is a crisis of historic proportions," said city Health Commissioner Thomas Farley, who said the rise of fentanyl represented a new wave of the opioid epidemic.

"We already had a crisis with the overprescribing of pills, and then with very pure heroin, and then fentanyl added gasoline to the fire. It really hit the city extremely hard," he said.

Deaths spiked in the summer, but declined somewhat from that peak in the last two quarters of the year. Still, Philadelphia has the highest drug death rate of any major U.S. city.

Despite the dip, the death rate in the second half of 2017 remained higher than in any prior year. It's not known why the rate went down, but the Health Department pointed to several large drug seizures and arrests toward the end of the year, the closure of the Gurney Street heroin encampment in Kensington, and widespread distribution of the overdose-reversing drug naloxone for saving lives.

It's too early to tell whether 2018 will see even more fatal overdoses, Farley said. But deaths were on the rise again by the tail end of 2017.

Drug Overdose Deaths by Quarter in Philadelphia

"We saw a dip between August and November, which was very good to see. But in December it jumped back up again," he said. "There's no guarantee that the decrease you see [before the end of 2017] will continue."

Overall, drug deaths in 2017 increased by 34 percent over 2016, and opioids were present in more than 88 percent of cases — up from 80 percent in the previous year.

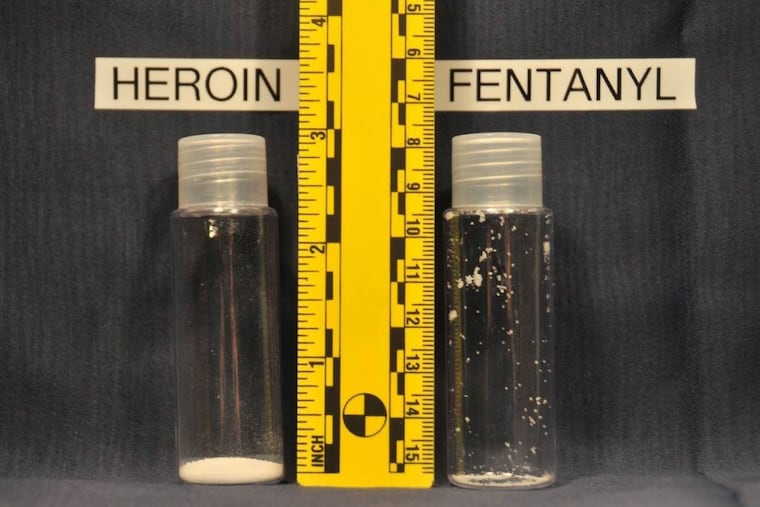

Fentanyl, the synthetic opioid that is much more powerful than heroin and typically used to cut the weaker drug, was present in 846 cases. That's a 95 percent increase over the previous year.

The Medical Examiner's Office found the rate of death among men jumped by 60 percent last year. Among women, overdose deaths increased by 16 percent.

The opioid epidemic has often been described as a predominantly white crisis. But the city data indicate that overdose rates are rising among people of color, too: Among Hispanics, opioid-related overdoses jumped 60 percent in 2017; among blacks, the opioid overdose rate rose 34 percent. Whites saw a 47 percent increase in opioid overdose deaths — and still comprise the largest share of deaths.

More people died in Port Richmond and Kensington than any other neighborhoods, the Medical Examiner's Office reported. But "new hot spots emerged" in South Philadelphia, West Philadelphia, and the Northeast. And most people who died in Philadelphia lived in Philadelphia, the office reported, debunking the notion that large numbers of people from other areas are overdosing in the city.

Activists in Kensington said the last year's toll had been devastating. It is hard now to find someone in the outreach community or in addiction who had not been traumatized by the death of someone close. They praised the city for handing out more naloxone last year and said those efforts had to continue.

Farley said the city's efforts to stem the crisis — developed by its opioid task force last year, as the death toll began to rise — will continue. The Health Department is encouraging residents to carry naloxone, asking doctors to prescribe fewer opioid medications, and trying to expand treatment to the thousands of Philadelphians who struggle with addiction. And 2017's soaring death rates are proof, he said, that the city needs to implement solutions once considered too radical, such as a safe-injection site.

"When you have 1,200 people who die in a single year, you rethink your assumptions and consider things you might not have considered otherwise," he said. "We can't overlook any approach to this."