Opioid overdoses sending more people to ERs, especially in Pennsylvania, Delaware

Analyzing emergency room data is a quicker way to track overdose trends; data from death certificates takes longer to compile.

Emergency rooms around the country saw a spike in patients overdosing on opioids last year, according to data collected by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and released Tuesday. And those visits — viewed as a harbinger of overdose death rates — are growing particularly quickly in Pennsylvania and Delaware.

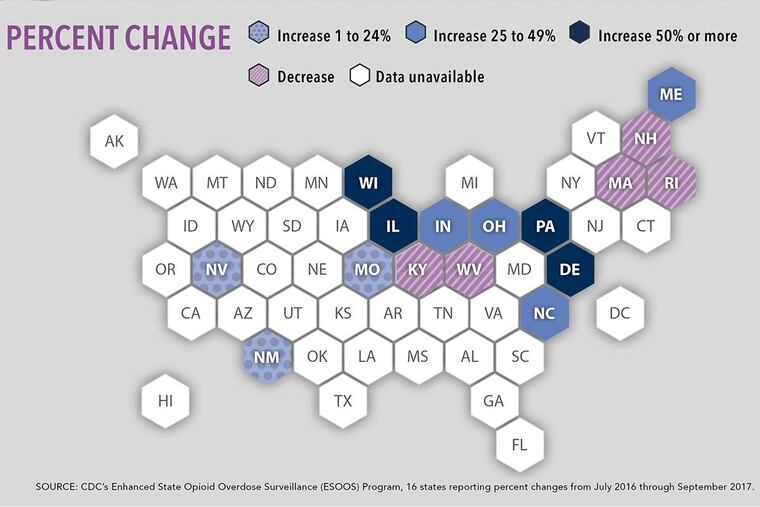

Drawing on overdose data from 45 states between July 2016 and September 2017, CDC officials said ER visits for opioid overdoses rose in every region of the country, with the Midwest seeing the largest spike.

Overdose visits increased across all demographic groups: men (30 percent), women (24 percent), and all age groups above 15, though the highest increase, at 36 percent, was recorded among people ages 35 to 54.

>> READ MORE: More babies are born dependent on opioids, but does Pennsylvania know the real scope of this crisis?

The agency also released specific data for 16 states that are among the hardest hit by the opioid crisis and get extra funding to report overdose data more quickly. Among those states, Delaware and Pennsylvania, along with Wisconsin, topped the list of states where the rate of ER visits for overdoses grew the most quickly. In Wisconsin, visits spiked 107 percent between July 2016 and September 2017, compared with 105 percent in Delaware, and 81 percent in Pennsylvania, with by far the largest population of the three. That's in line with early overdose death reports from those states, officials said. (New Jersey is not part of this study.)

Area doctors and health officials reacted with concern to the numbers. "Pennsylvania had already been a high use state and to see that kind of a jump is disheartening," said Dr. Michael Lynch, medical director of the Pittsburgh Poison Center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, which encompasses 20 hospitals throughout the state and saw about 1,300 overdose cases in the first six months of 2017 alone.

Acting CDC Director Anne Schuchat said it was likely too early to tell what was behind the increased overdose rates in Pennsylvania and Delaware, though changes in the local drug supply might be to blame.

In Philadelphia, officials say they suspect the spread of the synthetic opioid fentanyl — several times more powerful than heroin and often substituted for its less potent counterpart — is leading to the city's staggering overdose numbers. An estimated 1,200 people died of drug overdoses last year in the city. The CDC's latest report reinforced for local officials the depth of the crisis nationwide.

"Frankly what was surprising to me was the magnitude of increase in some states — seeing that on paper and recognizing that so many states are grappling with this was an eye-opener to me," said Jeffrey Hom, a physician and policy advisor in the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

Major metropolitan areas shouldered the brunt of overdose spikes: Large cities in the 16 states surveyed saw a 54 percent increase in ER visits.

>> READ MORE: In Philadelphia, fentanyl-cocaine overdoses point to an unpredictably deadly drug supply.

Some states surveyed did see decreases in ER visits: Overdose visits in Kentucky — among the hardest-hit states in the opioid epidemic — dropped 15 percent. Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island reported smaller decreases. It's unclear, Schuchat said in a press call Tuesday afternoon, whether those states are seeing the beginning of a persistent decline or simply a "statistical fluctuation."

Analyzing emergency-room data is a quicker way to track overdose trends. "Long before we receive data from death certificates, emergency department data can point to alarming increases in opioid overdoses," Schuchat said. She called ERs "essential hubs" in the fight against the opioid epidemic and said the CDC recommends that emergency departments institute "warm handoffs," a practice in increasing use in the Philadelphia region, where people in addiction can be sent directly to treatment from the ER after an overdose.

Still, many people who overdose never visit a hospital, either because they die before reaching the hospital or because they are revived with the overdose-reversal drug naloxone and decline to go to the hospital.

For that reason, it's often difficult to get a full picture of non-fatal overdose cases in a given area, said Dr. Joseph D'Orazio, the director of the Division of Medical Toxicology in the emergency department at Temple University's Lewis Katz School of Medicine. Last year, as part of the mayor's task force on the opioid crisis, he and other clinicians recommended that the city institute a program that collects real-time data on overdoses around the city.

He recalled a five-day stretch in December 2016 when 35 people died over overdoses. "That was something that was very visible on a boots-on-the-ground level, to EMTs and doctors and emergency departments, but could not be tracked very easily from a public-health standpoint," he said. "We don't have a real-time data network set up."