Pa. overdose deaths again rise, but Philly no longer No. 1

Still, overdose deaths jumped nearly 30 percent in the city, and fentanyl was increasingly a culprit.

Drug-overdose deaths rose again in Philadelphia and statewide last year, but the city lost its No. 1 ranking as fatalities spiked more significantly in rural areas, according to a Drug Enforcement Administration analysis released Thursday.

Among the 67 counties, Philadelphia ranked fifth in overdose deaths per 100,000 people, behind four counties in south-central and Western Pennsylvania, the DEA said in its annual report. Fulton County, ranked No. 32 in 2015, came in at No. 1 in 2016 with a rate of 74 deaths per 100,000.

"The issue is not limited to the inner city but affects the entire state at large," Gary Tuggle, special agent in charge of the DEA's Philadelphia field division, said at a news conference.

It was the first time since this data gathering began in 2013 that Philadelphia did not have the highest countywide rate. But overdose deaths did jump nearly 30 percent in the city — from 702 in 2015 to 907 last year, the report said.

"This is not a new problem for us, but by God, this is the worst it has ever been," said Jeremiah A. Daley, executive director of the Philadelphia/Camden High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) program.

The 2016 numbers, compiled from coroners and medical examiners and analyzed by the DEA local office and the University of Pittsburgh, tallied 4,642 drug-related overdose deaths in the state — an increase of nearly 37 percent. Deaths were attributed to fentanyl and similar substances, heroin, cocaine, benzodiazepines, prescription opioids, or other illicit drugs.

The report provides comprehensive data about who has overdosed and where, something that officials said is not compiled anywhere else and will offer "a road map for how we are to combat this crisis," said state Attorney General Josh Shapiro, who also spoke at the news conference.

"Day in and day out… [agencies] work side by side, share information, and work collaboratively," said Shapiro. His office is distributing 300,000 pouches to pharmacies and hospice and home-care organizations that deactivate leftover pills, making them safe to throw away when the pills are shaken in the pouch with warm water. They are to be given out with opioid prescriptions. "We've got to continue to tackle this in a multidisciplinary way," he said.

While larger percentage increases in overdoses were reported in rural areas, pointing to a steep spike in usage, in raw numbers the state's urban regions saw more than three times as many deaths as the rest of the state.

"Overdose from opioids is already a leading cause of death in Philadelphia, and the numbers continue their shocking increases," said Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley, noting that in Philadelphia, overdoses are the leading cause of death for age groups 15 to 24, 25 to 34, and 35 to 44.

In eight Southeastern Pennsylvania counties, 1,900 people died of fatal overdoses last year — more than any other region in the state. Death rates in Philadelphia's neighboring counties ranged from 40 per 100,000 in Delaware County to 28 in Montgomery County and 19 in Chester County.

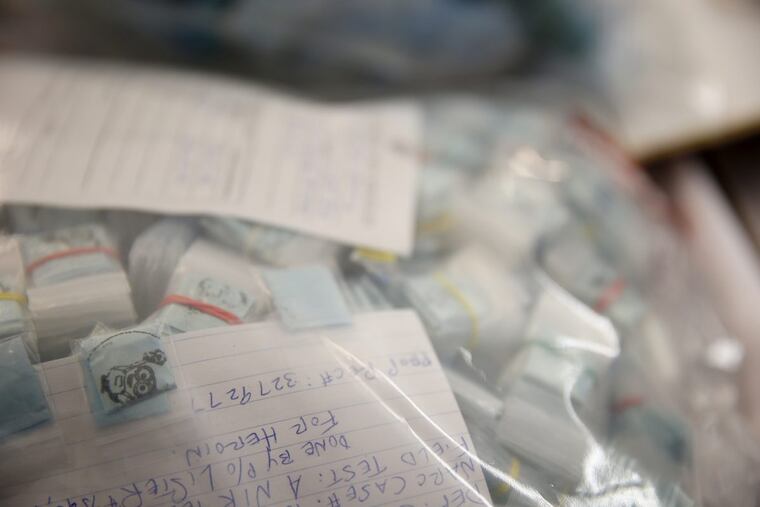

The number of deaths from heroin remained steady, but fatal overdoses involving fentanyl, a super-strong synthetic opioid often laced into heroin or taken separately, increased by 130 percent. In Philadelphia, it was present in the blood of nearly half of 2016's victims. And while fentanyl had often been disguised as heroin and ingested by unwitting users, drug customers are now intentionally seeking it out, the DEA analysis said.

The shift could be a "significant indicator" that Pennsylvania opioid users are changing habits — although fentanyl can cause a higher rate of deaths without a higher rate of use because it is so strong.

Only three counties, Cameron, Forest, and Warren, had no drug-overdose deaths.

Since 2013, law enforcement officers have reversed 3,800 overdoses using naxolone statewide. And of 11,000 calls the state help line, 1-800-662-HELP, has received, 50 percent ended in connecting the caller directly to treatment, said Jennifer Smith, acting secretary of the state Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs.

"We can't forget that every life is worth saving, and every person has the potential to recover," Smith said.