Safe injection site uproar reminds Rendell of needle exchange fight 27 years ago

Those involved in the struggle to open Prevention Point - Philly's only needle exchange - say the parallels are clear between that fight and the city's decision to encourage safe-injection sites.

It was an idea born in the middle of a devastating epidemic with an ever-rising death rate. It drew the ire of state officials, threats to arrest those who operated it, and fears that it would encourage drug use and addiction.

It was a needle exchange to prevent reusing hypodermic needles, and the year was 1991.

Twenty-seven years later, those involved in the struggle to open Prevention Point — still Philadelphia's only needle exchange — say the parallels are clear between that fight and the city's decision to encourage the opening of safe injection sites, where people in addiction can inject drugs under medical supervision and access treatment.

Back then, the epidemic was HIV/AIDS, frequently spread by drug users sharing needles. Today, the city faces an overdose epidemic — mostly opioids — that killed an estimated 1,200 people last year in Philadelphia. City officials say a safe-injection site will save lives and usher more into treatment.

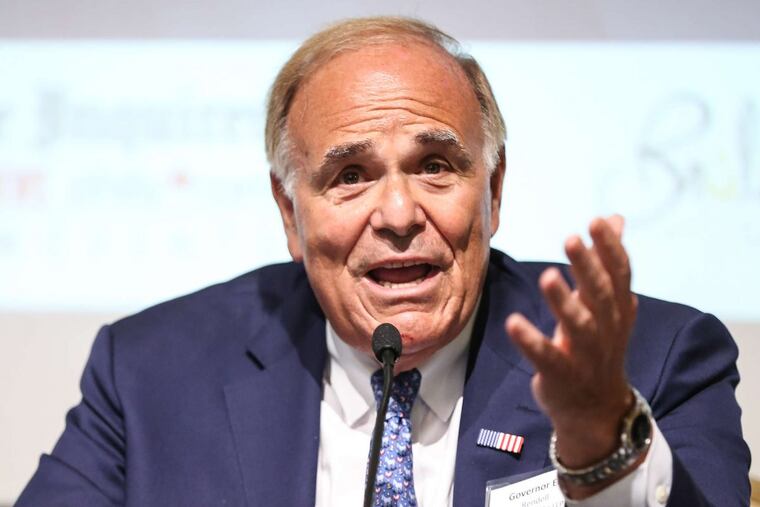

"It's the same thing," said former Gov. Ed Rendell, who legalized what had been an underground operation as one of his first acts as mayor in 1992. "We went through the exact same stuff that the Kenney administration is about to go through. And I strongly support the actions that Mayor Kenney has authorized. I think he deserves a lot of credit for having the courage and foresight to do this."

He added that he thinks the city should consider funding a safe injection site itself, though city officials stressed on Tuesday that they would leave the funding to private entities.

Jose Benitez, Prevention Point's director for the last 11 years, said he sees a clear line between the AIDS crisis and the opioid epidemic — which has now outstripped the death rate during the worst years of the AIDS epidemic.

"Then, you're talking about us having half of the new cases of HIV emerging among people who were sharing syringes," he said. "And we're now talking about an overdose death rate that's four times the homicide rate."

In the face of the opioid crisis, staffers there have taught thousands how to use the overdose-reversing spray Narcan — in a year, a single outreach worker there saved about 40 people from fatally overdosing — and, from their Kensington offices, offer outreach, medical care and treatment programs.

AIDS activists opened the needle exchange, unofficially, with the written support of Mayor W. Wilson Goode Sr. in 1991, when nearly half of the city's new HIV infections were caused by intravenous drug use, and obtaining syringes without a prescription was illegal. They operated in secret in Kensington — now the epicenter of the opioid epidemic — for months before Rendell officially authorized the program in July 1992.

Rendell said the tenor of today's criticism over safe injection sites reminds him of what he heard back then.

"There is no getting around the fact that distributing needles facilitates drug use and undercuts the credibility of society's message that using drugs is illegal and morally wrong," Bob Martinez, then President George H.W. Bush's drug czar, wrote in a federal report on needle exchanges in 1992.

Rendell had been wary of the concept before a meeting with his health commissioner and police chief. "I was a former district attorney, and the first time they brought me the idea of a needle exchange, I instinctively reacted negatively."

He said he was convinced otherwise in less than an hour: People in addiction "would shoot up whether we had Prevention Point or not — but if not, they would use dirty needles and that would promote the spread of AIDS," he said. "And people with doubts of the efficacy of this program should look at what a success Prevention Point has been over the last 25 years."

In 2011, a city report cited the needle exchange as a factor in a consistent decline in the number of injection-related HIV cases in Philadelphia, where the new infection rate among people who inject drugs has been dropping for years.

But after Rendell authorized the needle exchange, the state health commissioner threatened to arrest its operators, the former mayor recalled. He responded that they should arrest him first. On the first day Prevention Point officially opened in Kensington, no arrests were made.

"It's the same fight today," said the city's newly elected district attorney, Larry Krasner, who was retained as Prevention Point's legal counsel during its early days, when organizers feared arrest. "I see them as very parallel. And it is wonderful that Philadelphia is on the right side of this, and early."

Some early reactions to the safe injection site announcement have been strong — House Speaker Mike Turzai called it a "stark violation of federal law" and urged Gov. Wolf to send the city a cease-and-desist order. Both then and now, these ideas remain controversial among many in the neighborhood. But Benitez and Rendell said that the conversation around harm-reduction measures like needle exchanges has changed dramatically in the decades since Prevention Point fought to open.

Wolf declared an opioids emergency this month, Benitez noted, and, while he has not expressed support for a safe injection site, he has not signaled he would move to shut one down, either.

"The city's attitude, the public's attitude, wasn't anywhere near what it is today about the use of narcotics," Rendell said. "I think the opioid epidemic is so pervasive that I think the public will support this. But whether they do or not, it's the right thing to do."