'Abdominal vomiting' device that raised eyebrows shows promising results

AspireAssist won Stephen Colbert some laughs, but gradually it is also finding more support among the weight challenged and their physicians.

A locally produced weight-loss device that started out as the butt of late-night TV jokes appears to be growing in popularity and credibility.

AspireAssist, manufactured by Aspire Bariatrics of King of Prussia, was described as "machine-assisted abdominal vomiting" by TV host Stephen Colbert before it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016. It had already been in use in Europe for several years.

But early jokes aside, European research presented at the Obesity Week conference in Maryland in October showed weight-loss results that were better than those in the product's FDA clinical trial.

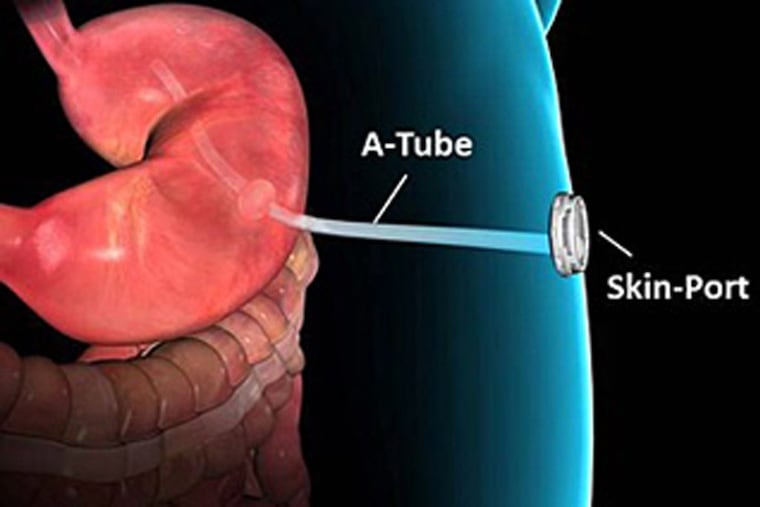

The device is a surgically implanted stomach tube that allows patients to drain about 30 percent of the calories of a given meal through a port valve into an attachable bag located outside their body. The contents can be disposed of in a toilet.

The European study – which was conducted with 160 patients in Sweden, Spain, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, and Italy — found a mean weight loss of about 19 percent in the first year, compared to 12 percent in the device's U.S. clinical trial. The patients continued to lose weight in subsequent years, but at a considerably lower rate. In AspireAssist's U.S. trial, the control group patients who used more traditional weight-loss methods had an average 3.5 percent weight loss.

Company president Katherine D. Crothall believes the new research findings will encourage more people to try the device. She said it is appealing to patients who want an alternative to other bariatric procedures, some of which are not reversible, and who want to be able to decide when they use the device.

The product's manufacturer says it is now being used by about 1,000 patients in the U.S. and abroad, with more health providers joining those who already have made it available to their patients.

"We have patients writing that, 'For the first time in my life, I feel like I have control,'" said Crothall.

An early concern in the U.S. was that the device could be seen as a form of sanctioned bulimia. The FDA and the manufacturer have said the tool is intended for adults ages 22 or older who are obese and should not be used by people with eating disorders. In addition, for the device to work properly, the patient needs to chew food thoroughly, Crothall said.

"What we're seeing is patients are developing better eating habits," she said. "They learn to chew very slowly."

One drawback is the device is not generally covered by health insurers, though Crothall said the company and providers have had success advocating for patients. The first year cost ranges from $8,000 to $13,000, which includes the device, the surgical procedure and follow-up care.

The limited number of devices in use reflect some of those insurance coverage issues, as well as reluctance about the device on the part of some providers.

Caitlin A. Halbert, a bariatric surgeon at Christiana Care's Wilmington Hospital, is not using the AspireAssist on patients.

"Bariatric surgeons have an obligation to carefully evaluate both the safety and effectiveness of any new weight-loss treatment that they considering using. To date, this procedure lacks any long-term data regarding its safety and efficacy," Halbert said.

David Tichansky, director of bariatric surgery at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, expressed bulimia concerns after the device got FDA approval. He said that he doesn't currently use it for patients and does not intend to.

David E. Loren, associate director of gastrointestinal endoscopy at Jefferson, said he plans to start offering the device to patients.

Regarding eating disorder concerns, Loren said, "bulimia is a defined disorder with emotionally driven binging and purging that fundamentally differs from a physician-guided and medically sound approach to obesity management."

Penn Medicine is working on a program to make the device available to its patients in the next couple years, said Anastassia Amaro, medical director of Penn Metabolic Medicine. Difficulty in getting the procedure covered by insurance is the main reason they haven't offered it sooner, she said.

Penn Medicine was one of the sites of the U.S. clinical trial, and Amaro is still overseeing two study participants who use the device.

The individuals, she said, have commented that the device has helped them learn to make healthier food choices and proper eating behavior. Their weight has fluctuated at times since the first year's loss, but they've been able to keep most of the weight off, she said.

"It is not for everybody, but select patients would benefit from it," Amaro said.