Child's seizures sent him, mother on trek

I walked into the emergency room and immediately knew something was very wrong. In front of me was an emaciated boy writhing in bed, almost dancing from head to toe.

I walked into the emergency room and immediately knew something was very wrong. In front of me was an emaciated boy writhing in bed, almost dancing from head to toe.

He appeared thin and wasted and locked eyes with me, just staring. Drool poured out of his mouth, his lips twitched continuously, and his head bobbed uncontrollably.

I introduced myself and asked his mother, Ana, how long her son had appeared like this. In Spanish, she said her journey here had been long, and he had slowly become this way over several years. Arturo continued to "dance" in bed, unable to speak and seemingly unable to control any part of his body.

Ana told me Arturo hadn't spoken since he was 5 but said he still laughed with her and seemed to understand what was happening.

Very quickly, I got the sense there was much more to this story.

Arturo was born in the United States and lived here until about age 4 or 5. His last recorded medical visit was for his fourth-year vaccines. Multiple medical visits in the U.S. indicated he was healthy during that time, although comments were made in the chart of his mother's concern for his "weird" gait. Nothing abnormal was found on his newborn screen or subsequent physical exams.

Arturo and his mother moved back to Guatemala when he was 5 to be with the rest of the family, Arturo's two older sisters and father, Javier.

A Mexican medical report showed Ana remained concerned about her son's progressive inability to walk and his regression in other developmental milestones, including speech and the ability to feed himself and chew and swallow solid food. Physical exams and studies in Mexico were inconclusive and showed only an unsteady gait and an MRI that yielded no answers.

Unable to find a doctor in Guatemala or Mexico who could help them, Ana told us she decided to bring Arturo here to "find a cure and because you offer the best medical care in the world."

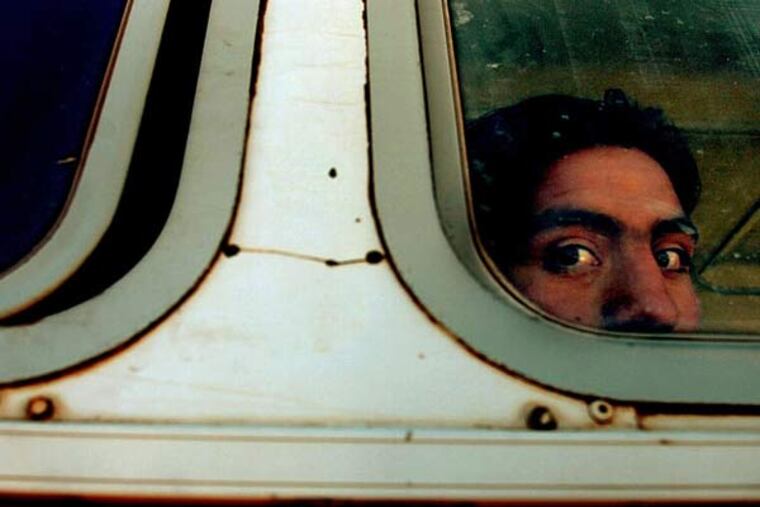

Ana put 10-year-old Arturo on her back in a sling, walked across the Guatemala-Mexico border, hopped a bus to and walked across the Mexico-U.S. border, then took multiple bus rides over the span of three days from Tucson, Ariz., to Wilmington. The journey spanned 4,500 miles, multiple buses, and took about a week. During that time, Ana spoon-fed Arturo baby food to keep him alive.

In the hospital, Arturo's vital signs remained normal, and other than his neurologic exam and emaciated appearance, his exam was remarkably normal.

Solution

Soon after his arrival, Arturo had four seizures overnight that his mother witnessed. Over the next three weeks, due to frequent seizures and inability to protect his clogged airway, Arturo developed an aspiration pneumonia. While we treated this, we continued to search for a diagnosis. We consulted multiple specialists, including pulmonology, GI, neurology, genetics, and social work. Among the diagnoses we considered were infectious causes such as tuberculosis or a parasitic brain infection, metabolic and genetic diseases, glycogen storage diseases, and lysosomal diseases, and various mitochondrial diseases. Biochemical screening labs for metabolic disease, EEG looking for seizure activity, routine malnutrition labs, and brain MRI all returned within normal limits, showing only nonspecific malnutrition.

Medical providers were stumped.

Our genetics team advocated strongly for a multi-thousand dollar genetics workup. No matter what Arturo's diagnosis, his disease was almost certainly incurable.

Because the family was uninsured and couldn't afford Arturo's ongoing care, the team debated the utility of searching for an answer. But our genetics team persisted.

Ana wanted Arturo's father to be directly involved in deciding and preferred to wait until he could be at the bedside with her to discuss the value of genetics testing and its implication for Arturo's future.

Arturo's father, Javier, however, remained in Mexico. Our social worker worked with an immigration lawyer to get Javier to Delaware. Javier, impatient to be at his son's side, attempted an illegal border crossing and was detained by immigration officials. After considerable negotiating by our social work team, Javier was released and joined his wife and son in Wilmington.

The family opted to push for a diagnosis, and so the panel of genetics tests was sent.

A few days later, we had our answer: Arturo had a rare form of Tay-Sachs disease called juvenile onset Tay-Sachs variant. As we expected, the prognosis is grim. Past cases resulted in death in 5 to 15 years.

Tay-Sachs is an inherited neurologic disease marked by progressive destruction of brain cells. It is characterized by decrease of functioning, loss of muscle coordination and speech, increase in seizures, and premature death. It is more common in Ashkenazi Jews, the Amish, and a few other groups. Variants such as Arturo's are seen in South American peoples, among others.

To maximize his quality of life for the time he has left, Arturo is undergoing physical and speech therapies, being tube fed to help his nutrition, and receiving communication assistance through specialists and the use of technology. Ana and Javier have settled into life in Delaware working minimum-wage jobs so they can participate in Arturo's care.

All of Arturo's hospitalization and diagnostic workup was paid for by charitable donors and the Nemours Foundation.