Why total solar eclipses have snubbed Philly - for centuries

The last time this region was graced with this major astronomical event, Philadelphia didn't even exist.

Not feeling the love from the sun and moon, Philadelphia, with only a partial solar eclipse on tap Monday? You don't know the half of it.

The last time our daytime view of the sun was totally blocked in this region, there was no Philadelphia.

The year was 1478, when the Leni-Lenape tribe held sway over the Delaware Valley. An ocean away in Poland, a boy named Nicolaus Copernicus, who would grow up to propose that the Earth revolves around the sun, was just 5.

The Philadelphia area and New Jersey will not see a total solar eclipse again until 2079 — marking a 601-year shutout from one of nature's most dramatic phenomena, said Ed Guinan, a professor of astrophysics and planetary science at Villanova University.

COMING MONDAY: Derrick Pitts, the Franklin Institute's chief astronomer, will take your solar eclipse questions live on Philly.com's Facebook page at 3 p.m., just after the eclipse's peak in Philadelphia.

During our celestial drought, Boston and Nova Scotia, site of Carly Simon's 1970 "You're So Vain" eclipse, have each enjoyed two total blackouts of the sun, according to EclipseWise.com, a site maintained by the retired NASA astrophysicist Fred Espenak. The area near Greenville, N.C., scored three.

Cosmic inferiority complex, anybody?

"We're getting cheated," said Guinan. "That's kind of sad."

Call it the law of averages on a grand scale.

The moon orbits the Earth once every 27 days, but in most cases it does not block our view of the sun, as its path is tilted by about 5 degrees. We see a total solar eclipse only on those rare occasions when the Earth, moon, and sun are lined up in a row, and only then if we happen to be at a spot on Earth that has spun around at just the right moment to catch the show.

Any given location on Earth should expect to see a total eclipse every 375 years, according to seminal calculations published in 1982 by the Belgian astronomer Jean Meeus.

But that's a long-term average. Some places get them far more frequently, while others have to wait. NASA's map of historic eclipses in North America reveals a series of interlocking, curvy paths with no apparent rhyme or reason.

It's hard to say exactly why the Philadelphia area has gotten short shrift, though presumably it should "catch up" in the centuries to come. As a mid-latitude city, it is relatively well-positioned to be struck by the lunar shadow, said Guinan, who usually casts his eye much farther afield. Last year, he helped to determine that a newly discovered planet, Proxima b, located nearly 25 trillion miles away, might have water on its surface.

Even when unable to see total eclipses in person, local scientists of yore were avid students of the partial variety. (On Monday, the peak of the event occurs at 2:44 p.m., with the moon covering 75 percent of the sun.)

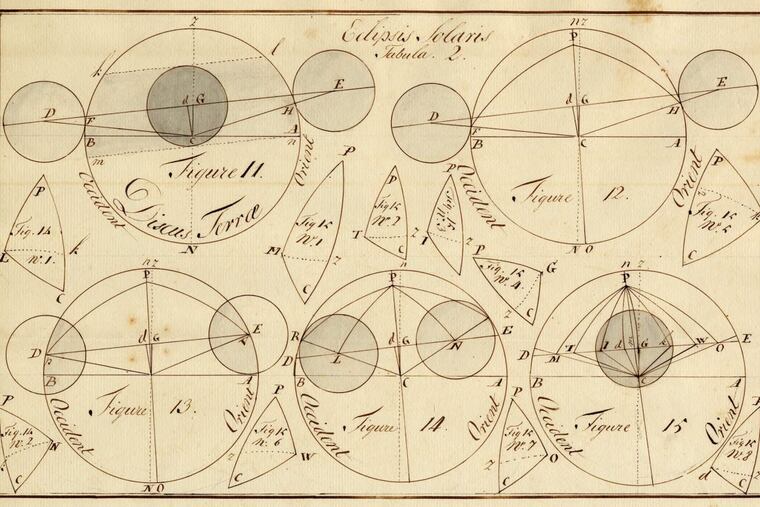

Allentown astronomer Daniel Freehauff drew up detailed calculations and illustrations for the eclipse of 1778, during which the moon blocked 95 percent of the sun in this region. In his sepiatone manuscript, housed at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, he wrote passionately of how the moon's shadow crept across our "terraqueous globe."

"Indeed the actual exercising of Astronomy is very delightfull: because it put us in particular Familiarity with Things so strange, and which nature about their surprising Distance seems to keep in the dark forces," he wrote.

Benjamin Franklin caught a good one during a 1726 sea voyage from London to Philadelphia, according to Smithsonian.com.

"We were surprised with a sudden and unusual darkness of the sun," he wrote. "We discovered that that glorious luminary laboured under a very great eclipse. At least 10 parts out of twelve of him were hid from our eyes."

Known both for his science and his satire, Franklin later used his withering pen to mock astrologers — those who believed that eclipses could be used to predict the future. In 1735, writing as Poor Richard, Franklin joked that the following year's six eclipses (four of the sun, two of the moon) "portend great Revolutions in Europe, particularly in Germany."

The study of eclipses was important beyond the field of astronomy, said Pedro Raposo, a curator at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. Careful observation of eclipses enabled 18th-century astronomers to get a more precise determination of the moon's orbit, which in turn enabled the calculation of longitude at sea. Navigators used sextants to fix their exact position.

"They could observe the motions of the moon against the background of the stars," said Raposo, an expert on the history of astronomy.

There is no telling just what the Leni-Lenape made of that total eclipse back in 1478. Relying on farming for some of its diet, the tribe had a deep appreciation of the varying positions of sun and moon, said John Norwood, a councilman of the Nanticoke-Lenape nation.

In tribal lore, the sun and moon are brothers, and the tribe itself was drawn to the East Coast because that is where the sun comes up, he said.

"We're the people of first light," Norwood said. "And the moon was actually called the night sun."

For some lucky viewers Monday, this "night sun" will turn the day into night. Others will have to wait until 2079.