Little desire for women's sex drug

The presumed vast numbers of women with low libido are not that hot for the first drug ever approved to heat up their desire.

The presumed vast numbers of women with low libido are not that hot for the first drug ever approved to heat up their desire.

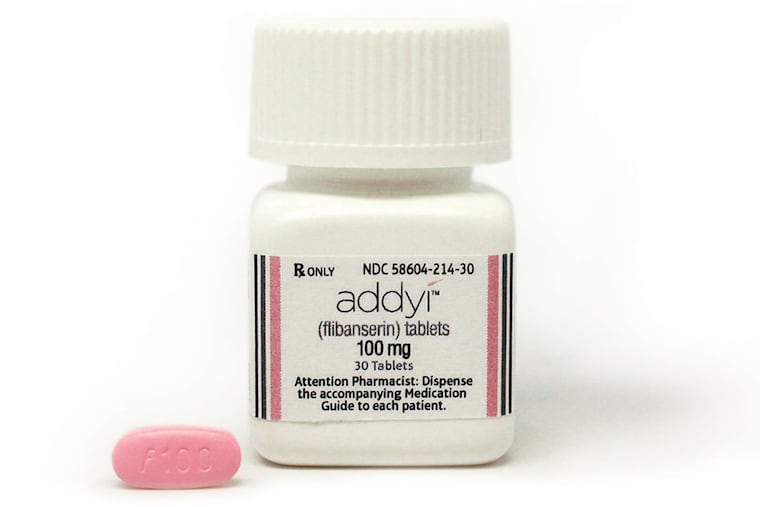

A total of 1,841 prescriptions for Addyi were filled in its first 10 weeks on the U.S. market, according to health-care industry analyst Symphony Health Solutions. (Viagra, the first erectile dysfunction drug, tallied more than 36,000 prescriptions in just its first week in 1998.)

At this rate, Valeant Pharmaceuticals International will need a long time to recoup the $1 billion it pledged to pay to acquire Addyi two days after regulators greenlighted the product in August.

Addyi's slow start is understandable: the daily pill is pricey ($26 per tablet), not usually covered by insurance, not a lot more effective than a placebo, and users have to swear off alcohol to avoid triggering the erstwhile antidepressant's most worrisome side effect - dangerously low blood pressure and fainting. Plus, Addyi is approved only for premenopausal women.

Still, cheerleaders and critics of the controversial approval see it as a watershed. Fans say Addyi has validated an important premise, one that detractors call misleading and profit-driven: that women's sex problems can be fixed with drugs.

"The framing of female sexual problems as brain disorders and as medical crises that need medical solutions is a misunderstanding of sexuality that can have great power over and above this particular drug," said Leonore Tiefer, a New York University psychiatrist and sex therapist who opposed the approval. "This drug has bad side effects, but that hasn't pulled the rug out from the basic myth that sexual desire is reducible to brain activity."

At S1 Biopharma in New York City, which is developing a drug that tweaks three brain chemicals involved in female sexual excitement, CEO Nick Sitchon said, "In the next five years, the industry will see a tremendous growth in this therapeutic area. The first drug has finally been approved, showing the FDA is willing."

Drug developers have been trying for decades to find remedies for female sexual dysfunction, or FSD.

But FSD has proved far more difficult to define and quantify, let alone fix, than erectile dysfunction, or ED.

As Sitchon acknowledged, scientists can't even agree on the components of "hypoactive sexual desire disorder" (a.k.a. low libido), the most common form of FSD. Is low libido a lack of desire, or lack of both desire and arousal?

The prevalence of low libido is another issue, with wildly varying estimates of 10 percent to 43 percent of women.

Doctors have long prescribed testosterone "off label" to such women, and the quintessential male hormone may yet become a ladies' product. Acerus Pharma in Canada, for example, is testing a testosterone nasal gel for "female orgasmic disorder." But two costly testosterone-for-women flops - Procter & Gamble's Intrinsa patch and Biosante Pharmaceuticals' Libigel - haunt the industry. Viagra, which treats impotence by improving blood flow, also failed with women.

Addyi, generic name flibanserin, has its own bumpy history. Originally studied by a German company as an antidepressant, flibanserin was twice rejected as a libido-booster by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration over concerns about serious risks versus modest benefits.

Sprout Pharmaceuticals, the tiny Raleigh, N.C., firm that acquired flibanserin, appealed the second refusal and was allowed to address safety questions with several small additional studies.

But Sprout did more than that.

It marshalled allies, including some women in Congress, for a high-profile "Even the Score" campaign that accused the FDA of sexism for approving a raft of sexual dysfunction drugs for men but none for women. Nonsense, the FDA countered.

Sprout also paid for allies to travel to an FDA advisory panel hearing. Women who took Addyi in a study testified that it had saved their marriages.

Sprout CEO Cindy Whitehead stressed that humanitarian aspect in interviews in recent months.

Valeant's $1 billion acquisition of Sprout is "an opportunity for us to make good on the mission," Whitehead told Fortune Live on Dec. 4. "Now we're going to march across the world for all the women who need treatment. And offer treatment in an affordable way."

She was referring to Sprout's "affordable access" program; women with health insurance can get three months of Addyi for $20 a month, instead of $780 a month.

Five days after that Fortune interview, Valeant announced Whitehead was out as CEO.

Sprout hasn't yet begun direct-to-consumer advertising, which could stoke demand.

But the FDA imposed precautions that analysts predicted would limit Addyi's market.

The labeling prominently warns that "severe low blood pressure and fainting" can occur when flibanserin is combined with alcohol or some common medications, including over-the-counter remedies and herbal supplements.

Doctors who prescribe Addyi must take 15 minutes of online training to be certified to counsel patients not to drink alcohol. Pharmacists can dispense Addyi only to certified physicians.

By early December, Sprout had signed up 10,000 doctors and 30,000 pharmacies.

The Symphony Health data show the 1,841 prescriptions, worth about $1.6 million, were filled between Oct. 2 and Dec. 4. Private insurers rejected 75 percent of claims, and public insurers rejected virtually all.

William Schlaff, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Thomas Jefferson University, said Addyi had been prescribed "little, if at all, in our practice."

"Hypoactive sexual desire disorder is a complex issue which does not lend itself to a cure by a simple, magic pill," he said. "I am concerned that Addyi's slight benefit is often outweighed by the significant risks."

Whether Addyi catches on or not, drug developers seem to believe a new day has dawned.

"The Addyi approval removed the regulatory risk," said Stephen Wills, chief operating officer of Palatin Technologies in Cranbury, N.J. "We get money from investors and shareholders. They were a bit reluctant until the regulatory front was more illuminated."

Palatin's drug, bremelanotide, is a synthetic hormone that activates brain receptors involved in increasing sexual responses. The drug is now in the final phase of testing; if all goes well, Palatin hopes for FDA approval in 2018.

Like Viagra, bremelanotide is used as needed, although it has a potential turn-off: a pen-style injector. A nasal spray formulation was abandoned when it caused spikes in blood pressure.

Lorexys, the S1 Biopharma drug, is not as far along in development, but because it combines two already-approved antidepressants (bupropion and trazodone), the FDA has OK'd an accelerated path to approval.

Not coincidentally, Sitchon said, a key scientist working on Lorexys is Robert Pyke - inventor of flibanserin.

"He wanted to help develop what we feel is the next-generation drug," Sitchon said.

215-854-2720

@repopter