Unions in no hurry for new contracts

MORE THAN five months after city union contracts expired in June, Mayor Nutter has made little headway in his efforts to get employee pension and benefit changes in order to save the financially strapped city $25 million a year.

MORE THAN five months after city union contracts expired in June, Mayor Nutter has made little headway in his efforts to get employee pension and benefit changes in order to save the financially strapped city $25 million a year.

One reason may be that alone among the 50 states, Pennsylvania's labor laws have been interpreted to prohibit a public employer like the city from implementing new contract terms when it reaches an impasse with a union.

In effect, if a union is content with the deal it has and wants to stall, it can extend its contract indefinitely.

"It could last a long time," said labor lawyer Sam Spear, who represents the largest city union, District Council 33 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees.

The city must negotiate contracts with District Council 33, which represents blue-collar workers, and District Council 47, representing white-collar employees. Police and fire contracts are settled through binding arbitration.

Spear was an attorney in the court decision that established the unilateral implementation ban, a 1993 Commonwealth Court ruling on a contract dispute involving Philadelphia Housing Authority employees.

What kind of logic did the courts use to conclude that a contract could last forever if a union wants it to?

"The decision says that if you're in the public sector in Pennsylvania, it would be unfair if [an employer] could sidestep collective bargaining by saying, 'We can just implement this,' " Spear said. "You don't want one party to get an advantage by unilaterally implementing a contract."

Spear said that public-employee negotiations are different from those in the private sector, where unions can strike and stay out as long as they choose.

"In the public sector, the right to strike is limited," Spear said. "An employer can get an injunction when the strike affects the health, safety or welfare of the public."

Indeed, the court decision that barred PHA from imposing terms on unionized employees cited the need for "some balance in the economic weapons available" to the parties in the dispute.

In a dissenting opinion, Judge James Gardner Colins called the decision a dangerous precedent "that compels municipal corporations or authorities to continue to operate indefinitely under expired labor agreements regardless of the financial impossibility of doing so."

Shannon Farmer, the private attorney who is managing the city's negotiations with its two AFSCME unions, agreed that the PHA decision prevents the city from implementing its own terms, and that the ban "changes the dynamics of negotiations."

She said that the intent of the court in the PHA ruling was to "create bargaining among equals" in public-employee disputes but that the ruling "shifted the balance of power too far" in favor of the unions.

Farmer said a more recent court decision suggests the prohibition against unilateral implementation should last for a "reasonable period," but it's unclear what that period would be.

Spear and Farmer agreed that Pennsylvania is unique among the states in barring a public employer from implementing its terms.

"There are only nine or 10 states where public employees even have the right to strike," Spear said.

Because contract negotiations and strategies are confidential, it's unclear to what extent the ban on imposing new contract terms has affected current negotiations.

Cathy Scott, president of DC 47, which represents more than 3,000 white-collar employees, said the city hasn't scheduled a bargaining session since July 10.

She said that the union has been ready to negotiate but that the administration was focused for months on trying to get pension changes enacted in the state Legislature or City Council.

"I think there are certain attitudes with this administration that don't lend themselves to resolving things at the table," Scott said yesterday.

Negotiating sessions were scheduled for today and tomorrow for both AFSCME unions.

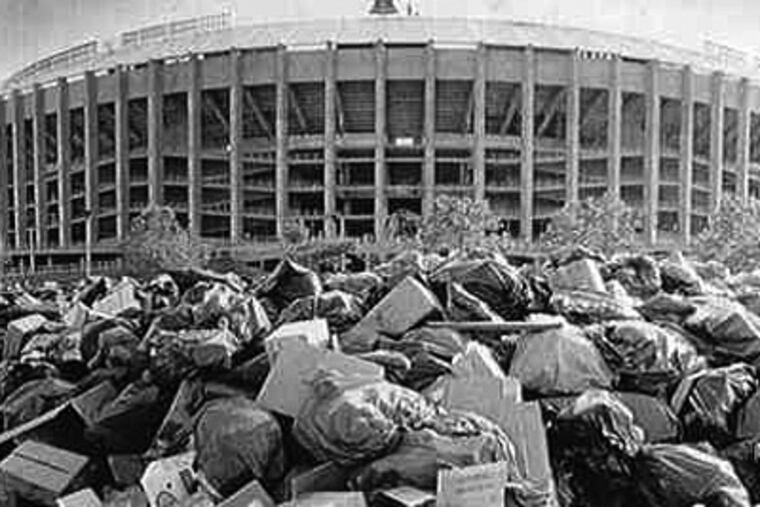

The contract dispute in some respects resembles the historic battle of 1992, when then-Mayor Ed Rendell sought big savings in employee benefits and other concessions, and the unions were in no hurry to either strike or settle.

Rendell eventually moved to implement new contract terms, and a court battle over whether his move was legal was never resolved, since the two sides managed to reach a deal.

It was after the 1992 contracts that the PHA decision established the prohibition on unilateral implementation.