Pa. fracking boom goes bust

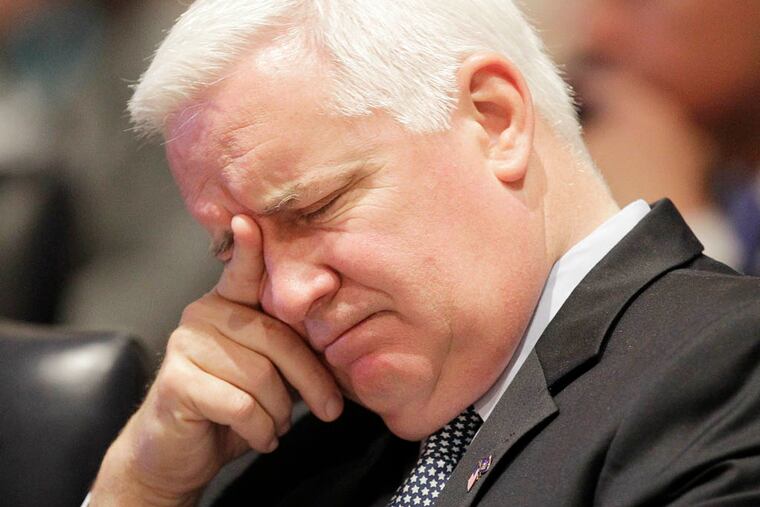

Corbetts pledge to create the Texas of the natural-gas boom rings hollow in wake of market collapse.

IT WAS JUST a couple of years ago that fracking was booming in upstate Pennsylvania's Bradford County, and Janet Geiger, a retired hospital worker living on a 10-acre spread near the New York border, could count on getting a $300 to $400 check every month from the gas giant Chesapeake Energy Corp., which was drilling under her land.

But both the gas and the checks - with the financially ailing Chesapeake now claiming big deductions - dwindled until finally, in March, a check never showed up. "I thought the mail had gotten lost," said Geiger, 74, but after a week she finally reached someone with the Oklahoma gas driller who explained "they didn't have a buyer [for the gas] that month."

But Geiger said that she'd already seen the signs of a slowdown, that rural streets once clogged with the massive trucks of the drilling firms were mostly empty now, while new motels that had been hastily thrown up or expanded to accommodate a flood of out-of-state workers had only a couple of cars in the parking lots.

It's been a little more than two years since a then-new Gov. Corbett famously pledged to make Pennsylvania "the Texas of the natural-gas boom" - but already it's beginning to look as if the governor was all hat and no cattle, at least on this issue.

By some measures, unconventional drilling for natural gas, or "fracking," in the Marcellus Shale formation in Pennsylvania has dropped by more than 50 percent since its peak in 2010, the year Corbett was elected. Experts say that's because of several factors - but the biggest by far is a steep plunge in the price that natural gas was getting on the open market, in part a result of so much fracking here and elsewhere.

But regardless of the cause, the end of the fracking boom in Pennsylvania, or at least a pause, has enormous implications - economically, environmentally and politically. The latest numbers show that new jobs in energy production in the state are flat at best - which could be another headache for Corbett as he defends his record on employment in what looks like an uphill battle for re-election.

Plunging prices

"The market collapsed - it's a classic case of supply and demand," said Dave Yoxtheimer, hydrogeologist and extension associate with the Penn State Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research, which closely monitors fracking. He noted that the Baker Hughes website, which traces the number of active drilling rigs, peaked in Pennsylvania at about 110 active locations in 2010 - the same year Josh Fox's documentary, "Gasland," sparked a new generation of environmental activism.

The large oil-and-gas companies like Chesapeake were flooding the zone with rigs in upstate and western Pennsylvania roughly five years ago, at a time when natural gas was fetching $13 per million British thermal units, and the U.S. was a major importer of liquefied natural gas.

But the rise of fracking technology - breaking apart shale and capturing trapped gases that once were inaccessible - brought so much natural gas onto the domestic market that the price collapsed as low as $2 per million Btu before rebounding to the current $3.30. Today, the Baker Hughes survey shows just 50 fracking wells operating in Pennsylvania, and Yoxtheimer said the bulk of new rigs instead are targeting oil, in regions such as the thriving Bakken field in North Dakota.

The falling gas prices came at the same time that environmental opposition increased and the regulatory climate toughened for fracking, which also may have played a role in slowing new drilling activity in the state.

In Wayne County, for example, two large energy companies that leased more than 100,000 acres at the height of the boom in 2009 - a move that promised to pump at least $187 million in lease payments into the Pennsylvania economy - announced earlier this summer that they now are canceling those agreements. The official reason was an ongoing drilling moratorium by the Delaware River Basin Commission, but officials also cited the depressed market for natural gas and a desire to drill instead for oil elsewhere.

Last month, the energy giant Royal Dutch Shell shocked Wall Street by taking a whopping $2 billion write-down in the value of its North American shale assets, including leases in Pennsylvania. Shell already had announced it was shifting its focus from natural gas to shale oil, and now its executives said even finding the trapped oil is harder than the company thought. Some officials have expressed concern for the future of a $2.5 billion gas-processing ethane cracker that Shell had been eyeing for western Pennsylvania, the signature economic-development project of the Corbett administration.

Mark Price, labor economist for Pennsylvania's liberal-leaning Keystone Research Center, said recent stats are beginning to show that jobs in the state's energy sector, which includes gas drilling, are starting to level off. He said one core measure of employment in the Marcellus Shale - which had risen steeply, by 10,000 jobs over 2011 - increased by only 1,000 positions last year. He said the broader energy sector, which includes more-up-to-date statistics, is posting a decline so far in 2013.

Going to Ohio

Price said that on a recent trip to Wellsboro, in far north-central Pennsylvania, "we talked to folks who knew people or who had family that had gotten jobs on rigs, and they had been asked to go to Ohio" - where drilling for wetter, more-profitable gas is booming.

"I think they've drilled and capped the wells and moved on to other states," agreed Nell Rounsaville, owner of the iconic Wellsboro Diner and another restaurant in the heart of Tioga County, although she said an increase in tourism business has offset the decline in rig workers. Advocates for fracking have touted the many spin-off jobs that more drilling would create in hotels, restaurants and other service industries.

But a decline in production may fall hardest economically on leaseholders like Sayre resident Geiger who came to expect sizable monthly payments when the gas was flowing. Now, in addition to the decline in drilling, she and her neighbors who signed leases with Chesapeake are mad that the Oklahoma-based firm - facing a cash crunch while its founder and former CEO is probed by the Securities and Exchange Commission - is taking large deductions for "postproduction costs" from the royalty checks that do come.

"We're paying for their bad management," she said.

And environmentalists who've been seeking tighter regulations or even a halt to drilling say that the new economic realities of fracking are a game-changer. David Masur of Philadelphia-based PennEnvironment said gas companies that once touted the benefits of cheap natural gas for the Pennsylvania economy are looking instead toward facilities to ship liquid gas to markets overseas, where prices are higher.