Increasingly, youths are entering U.S. alone and undocumented

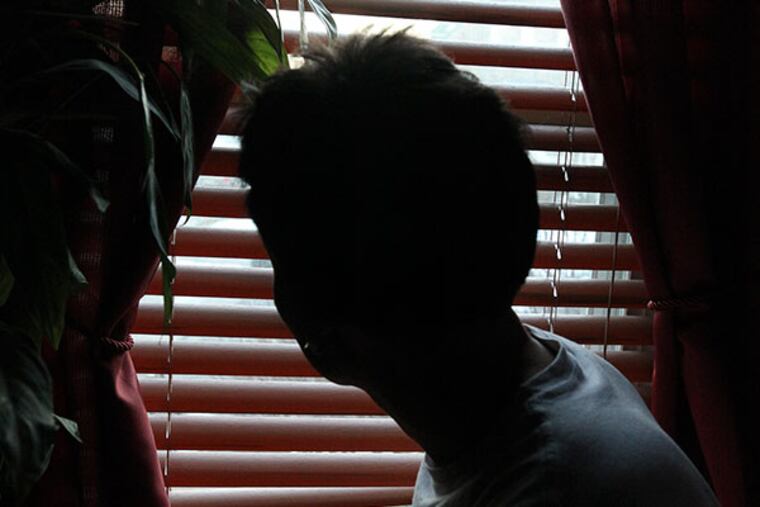

Many, like "Esteban" in Philly, flee violence and poverty in Central America.

ESTEBAN rode on top of seven cargo trains, narrowly escaped death at the hands of a Mexican gang leader and was robbed on his years-long journey from Honduras to Philadelphia.

He left home at age 12 with an older friend, fleeing an abusive stepfather. At 15, he waded across the knee-deep Rio Grande into Texas. Like many youths, he came to the U.S. because it offers "more opportunities," he said.

And like a staggering number of minors under 18, Esteban - not his real name - entered without papers and without a parent or adult guardian.

In the last two years, the number of unaccompanied children who have made the dangerous journey alone, and who have ended up in federal custody, has nearly quadrupled.

In fiscal year 2011, the Department of Homeland Security detained 6,560 unaccompanied youths, then put them in the care of the Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). In fiscal year 2013, which ended Sept. 30, that number soared to 24,668.

Most of these minors came from the Central American countries of Guatemala (37 percent), Honduras (30 percent) and El Salvador (26 percent). In the most recent fiscal year, only 3 percent came from Mexico.

The shocking surge in the number of children trekking into the country alone and without papers comes at a time when the total number of immigrants detained after entering the country illegally is at a 40-year low.

The New York-based Women's Refugee Commission went to the U.S.-Mexico border in June 2012 and interviewed 151 unaccompanied children.

Most said that "their flight northward had been necessitated by the increasingly desperate conditions of extreme violence and poverty in their home countries," the commission wrote in a report published last year, Forced From Home: The Lost Boys and Girls of Central America.

"Children from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador cited the growing influence of youth gangs and drug cartels as their primary reason for leaving," the report said.

Unaccompanied minors detained by Homeland Security have been transferred to ORR's care since 2003. Most are sent to ORR-funded private-care facilities and end up being placed in shelters, group homes, foster homes or residential treatment centers.

Meanwhile, they are also put into removal proceedings. Many are deported.

10 days in the desert

Esteban, now 18, had been detained by immigration authorities near the small town of Encinal, Texas, around April 2011, after crossing the river near Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, then walking 10 days through the desert and following train tracks up north.

"I couldn't find water. I arrived on the highway that goes to San Antonio and near there, I fell to the ground . . . fainted," he said in an interview conducted in Spanish this week. After immigration authorities took him into custody, he was flown to Houston, then to New York to be placed in an ORR-supervised shelter.

He came to Philadelphia in the summer of 2011 after Lutheran Children and Family Service was contacted by an affiliate organization to help find him housing. He now lives with a foster family in Philadelphia and attends a public high school here. The Daily News was asked not to publish his name to protect his safety.

Kirsten Witmer, a foster-care case manager at the Lutheran agency, said that after an unaccompanied minor is taken into custody, efforts are made to reunite the child with an immediate biological family member in the U.S., or if not, a relative or acquaintance. If the child doesn't have someone, and if he or she qualifies for legal relief, then long-term foster care is an option.

Attorneys with HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) Pennsylvania represent some unaccompanied children in Philadelphia Immigration Court, a Justice Department facility at 9th and Market streets in Center City. Staffers also travel to a Lehigh Valley shelter, the only ORR-funded facility in the state that houses unaccompanied migrant children, to speak to children about their legal rights.

With the help of the Support Center for Child Advocates, a nonprofit agency at 19th and Cherry streets in Center City, HIAS was able to get legal residency for Esteban under the federal Special Immigrant Juvenile Status law because of his stepfather's alleged abuse.

Of the youths HIAS represents before an immigration judge, "99 percent" are able to remain in the U.S., said Judith Bernstein-Baker, HIAS Pennsylvania's executive director.

"If they don't have a legal way to stay, we don't represent," said Liz Yaeger, a HIAS staff attorney. In many cases, children are allowed to stay because they've "been neglected or abused or abandoned by their parents," she said. Others were found to have been victims of human trafficking or faced persecution in their home countries.

Journeys of trauma

La Puerta Abierta (The Open Door), a nonprofit agency based in Kensington with offices in South Philadelphia and Upper Darby, counsels Latino children who entered the U.S. alone.

"In our work, we have seen a very high number of girls who have experienced sexual trauma," said Cathi Tillman, the group's executive director. For boys, many have undergone emotional and physical trauma, she said. And many youths have experienced the guilt of leaving their families behind.

In 2008, Esteban, then 12, left the home he shared with his mother, stepfather and siblings in Trujillo, on the northern coast of Honduras, and began his journey to the U.S. with a 16-year-old friend.

They took buses to the western border of Honduras, then a taxi to cross into Guatemala. After boarding more buses toward the Mexican border, they met a man who said he could drive them to the river separating Guatemala from Mexico, where they could catch a boat. The man charged each boy 2,000 Mexican pesos (about $154 at the current rate). Esteban later found out the cost of the short car ride should have been just 5 pesos (39 cents).

He would spend a longer time in Mexico than he expected. "I didn't know how much farther it was still" to the Mexico-U.S. border, he said. In Mexico, he ran out of money. At times, he got food from shelters for migrants, or from people who lived along the train tracks.

On top of seven speeding trains, he sat sideways, watching the mountains and shacks pass by. When a train entered a tunnel, he ducked.

On the first train, thousands of migrants clambered onto the roof, he said. In Oaxaca state, the train derailed, and the migrants were accosted by armed members of the Zetas gang, who robbed the travelers and killed several people, he said. Two people, including a boy, died falling from the train during the chaos, he said.

Later in the trip, his friend decided to return to Honduras. Esteban forged on.

'Boss of the Zetas'

North of Mexico City, he worked in the house of someone who he first thought was a "coyote," or smuggler. He thought the man could help him cross the border.

He found out, though, that the man was a "boss of the Zetas" gang, he said. After the man realized that Esteban had no relatives in the U.S. from whom he could extort money, he planned to kill him.

The man drove Esteban to a garbage dump. "He took out a gun, but thanks to God, [another] man came out and defended me," Esteban said. While the other man argued with the gang leader to leave Esteban alone, Esteban said, he was able to run away. He eventually made his way to a train station.

This time, he rode alone on top of a train a few hours north to San Luis Potosi. He would later make it farther north to Monterrey, in northeastern Mexico, where he spent three years working in a factory making plastic car fenders. At 15, he continued his trek, finally wading across the Rio Grande into Texas.

The Lutheran agency's Witmer said she realizes that some people may not sympathize with someone like Esteban, but added:

"I think all of us have been on the receiving side of grace. . . . We're all human. How would we feel if these are our family members?"