Karen Heller: In Philadelphia, books for the blind head for the trash

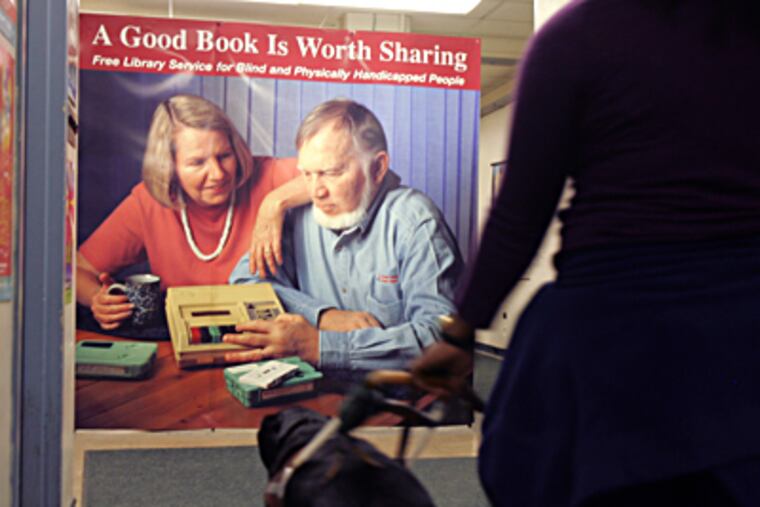

Keri Wilkins is incensed. She is a librarian passionately committed to serving the blind and physically handicapped in 29 counties, the entire eastern half of Pennsylvania, sending out almost a million digital books and recorded cassettes a year.

Keri Wilkins is incensed. She is a librarian passionately committed to serving the blind and physically handicapped in 29 counties, the entire eastern half of Pennsylvania, sending out almost a million digital books and recorded cassettes a year.

"I am appalled. I am angry," she tells me at the branch at Ninth and Walnut, founded in 1882, the nation's oldest library serving the blind, where almost a half-million mint-condition recorded cassettes are, by state mandate, headed for "recycling," that is, the trash. "This is the minnow swallowing the whale. I have spent my whole year fighting this merger."

But the merger is scheduled to start next week and be completed by mid-month.

And it won't save a cent.

Or make service faster or more efficient for an already underserved community.

The merger requires transferring most of the Philadelphia library's more numerous audiobook collection and lending services to the Pittsburgh branch. Philadelphia provided 60 percent of the state's blind community and Pittsburgh 40 percent. Now, those services and funding will be flipped. Critics say having one central collection may ultimately cost more: Pittsburgh, where it will now be housed, averages higher per-patron annual costs and may need to hire more staff.

Fifteen jobs here are being eliminated, half the staff - with only five added in Pittsburgh, fueling concern of weaker and slower assistance - for a library built on customer service. Daniel Simpson, a patron for a half-century (his twin brother, too), calls staffers like Susan Horvath every other week for literature suggestions.

The consolidation was first proposed under the Rendell administration and announced to local administrators as a done deal in fall 2010. Critics say the decision was based on faulty research by a firm without library or blind-services experience, made largely by a now-retired Harrisburg administrator and with virtually no consultation from experts and stakeholders, the blind and physically disabled in eastern Pennsylvania.

The plan is opposed by almost everyone: the Free Library of Philadelphia, which manages the local branch; the National Federation of the Blind of Pennsylvania; and state legislators from both parties. Meanwhile, the Library of Congress, which produces all audio material, is seriously concerned about the loss of service. It upholds a national policy that prohibits transferring materials between network libraries. For now, Wilkins can't ship her blue digital books to Pittsburgh.

The consolidation appears to have been based on the assumption that the digital revolution would move more swiftly for the blind. There would be increased availability of recorded cassettes and access to digital downloads on e-books and home computers. This has not happened.

More than half the book titles for the blind remain available only on the older cassettes - the half-million headed for a dump in York. "About 10 percent of blind people use braille, which I love, but 100 percent of the blind use talking books," Simpson says. "So why are they moving or destroying the whole collection that everyone uses?"

As for computer digital downloads, "about 10 percent of people have that technology," says James Antonacci, president of the National Federation of the Blind of Pennsylvania. "Seventy percent of blind people are unemployed or horribly underemployed. Most people get their books not by downloads but by calling the library and getting the books from the mail for free."

Kristin Smedley, a Bucks County mother of two blind sons, says, "I need this library. I would love to see everything go digital, but we're not there yet. It can take a week to get a book from Pittsburgh. It takes a day from Philadelphia."

Activists have protested, attended meetings, and written letters, to no avail. They argue that there are more blind and physically disabled people in this more populous region. The library is used by the blind, the visually impaired, injured veterans, stroke victims, anyone incapable of reading a book. Library advocates like Simpson want "to halt this plan for six months to a year and revisit it with consumer input with correct information, put together some task force with some stakeholders to come up with the best plan."

Wilkins surveys the green cassettes headed improbably to the trash bin when readers want them, the blue digital books possibly headed to Pittsburgh. "This is going to hurt the citizens of Philadelphia and this region, and it's not going to save any money at all," Wilkins says. "You're doing no good. You're just making it so much worse."