Jenice Armstrong: The Brothers' Network was created for brainy Philadelphia guys

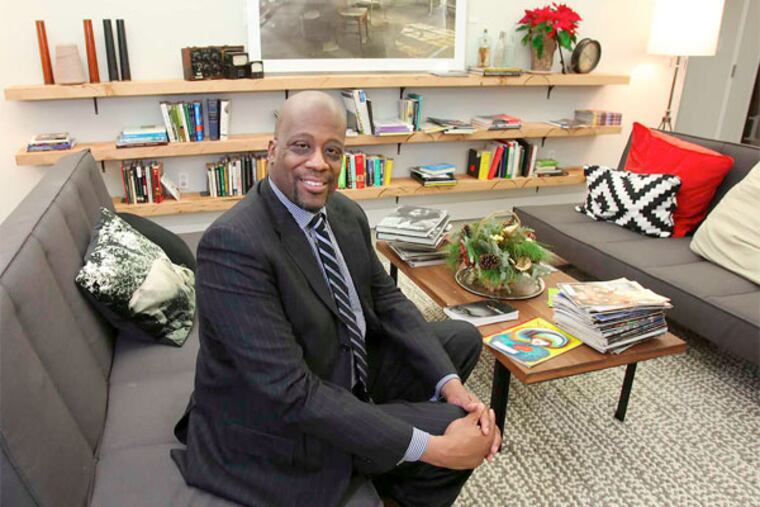

GREGORY WALKER, co-founder and managing director of the Brothers' Network, wants to assure you that he and his friends are not cornball brothers.

GREGORY WALKER, co-founder and managing director of the Brothers' Network, wants to assure you that he and his friends are not cornball brothers.

Still, that's how some folks might try to label them. After all he, along with a crew of 276 local African-American men who are part of the network, routinely read books, visit the theater and have lofty conversations about world events.

Their pants don't sag beneath their butts, and they aren't big fans of film director Tyler Perry.

They come from a wide swath of professions. Members range in age from 19 to 80 and include nationally regarded academics - and a 70-year-old house manager at a local theater. Besides the active members, another 1,000 follow the group online.

What they all have in common is a love of intellectual discourse.

Oh, and - sorry Rob Parker, the recently fired ESPN commentator who recently brought the "cornball" slur to the national spotlight - some of them do date white women. And like Redskins quarterback Robert Griffin III, whose racial identity Parker called into question, some of them also may be Republicans. But none of that takes anything away from their blackness.

"We are misjudged," said Walker, 49. "If we are well-spoken, well-traveled, somehow that falls out of the notion of what blackness is.

"That only shows how much we have to continue this work, to continue to reframe and change the narrative."

Building the net

The Brothers' Network began as a book club five years ago. Tony Monteiro, who teaches African-American studies at Temple University, is the co-founder. Its first meeting was at the Moonstone Arts Center above Robin's Book Store on 13th Street.

It was Walker's vision to bring black men together to attend cultural events and discuss matters uniquely of interest to them. One of the people at that first meeting said, "Oh, this will never work but because black men don't read." That only redoubled his efforts.

He went on the hunt for black men interested in the arts. At theaters and other cultural venues, he began collecting names.

"What we found is that when I would go to the theater is that black men were feeling this sense of isolation and maybe even some shame about being intellectual," he recalled. "If you're really smart, you don't always tell people. Sometimes you dummy it down."

He also piggybacked on a network of students and friends people that Monteiro knew from an informal men's group.

"Those men came, and they knew some other men who enjoy reading and those men came. So people just kept coming in a spider-network sort of a way," Walker said. "Because outside of the barbershop, there is not a space where African-American men can express their intellectual creativity and ideas in a nonjudgmental way. It does not exist in our society."

Beyond the barbershop

The brothers meet monthly, and much of what they do centers around the arts.

Last November, they had a wine-tasting hosted by wine specialist Byron C. Mayes, a longtime member of the group. Last December they hosted a panel discussion with theater types involved in the Philadelphia Theatre Company's production of "The Mountaintop," a dramatic reimagining of the night before the assassination of civil rights activist Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

On Saturday, they have a black-tie fund-raiser scheduled around a performance of the play. Proceeds will help them match a $25,000 Knight Foundation grant that members received to develop a festival honoring Henry "Box" Brown, a 19th century slave who freed himself by getting inside a box and mailing himself to abolitionists in Philadelphia.

The Brothers' keeper

The son of a restaurateur and a stay-at-home mother, Walker grew up in Connecticut, where he took honors classes and washed dishes in his dad's restaurants.

He studied economics and finance at the University of Connecticut, where he marched against South African apartheid and agitated for the creation of the King holiday. One of his first jobs was as a community organizer for civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson's presidential campaign.

He moved to Philadelphia seven years ago, where he's built a career as a political consultant. Among other projects, he's consulted with the Philadelphia Department of Health, organizing public health initiatives around HIV and AIDS prevention.

Walker, who lives in Center City, currently serves as Democratic Executive Committeeperson for Washington Square West. He's 6 feet 5 inches tall and practices Buddhism. He prefers yoga to basketball and green tea to coffee. He's single.

His pet peeve is with those people - he calls them "the black police" - who get that idea that if you dress nicely and speak well, that's somehow inauthentic.

He dismisses their presumption that "they can determine who is or who is not black based on how someone speaks or what they wear."

"I don't know where they got their credentials," he said. "One of the things I like to say is you can like NASCAR, hockey and the opera and you still can be white. No one questions your whiteness," he continued.

"But if you're black and you like those things, then somehow your racial identity and authenticity are questioned. We must change that."

Blog: philly.com/HeyJen

Email: armstrj@phillynews.com