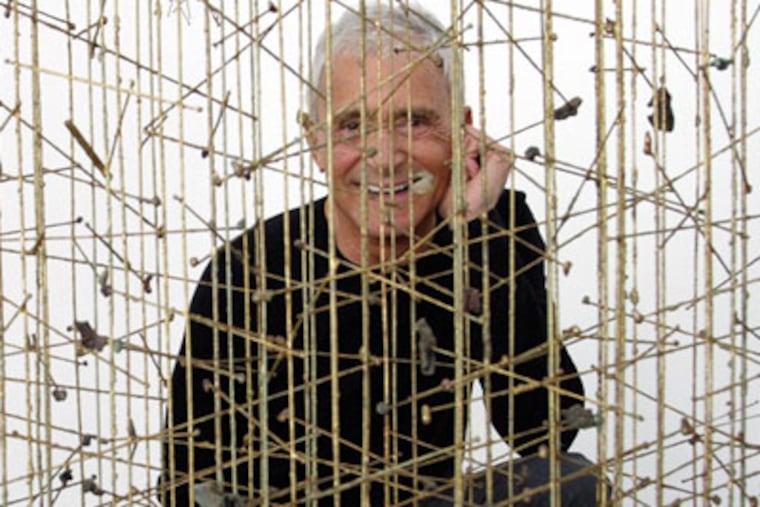

Vidal Sassoon transformed hair styling

It was 1988 and I was watching Salt-N-Pepa’s video for “Push It.” The rap stars danced in black catsuits and 8-ball jackets, and their hair was cut into these fierce asymmetrical bobs. “I want that haircut,” I told my mom.

It was 1988 and I was watching Salt-N-Pepa's video for "Push It." The rap stars danced in black catsuits and 8-ball jackets, and their hair was cut into these fierce asymmetrical bobs.

"I want that haircut," I told my mom.

"That?" said my mom, an expert on all things pop culture. "That isn't anything but a modified Vidal Sassoon bob."

She then went on to talk about Diana Ross and the Supremes and Twiggy and other fashion icons of her generation who wore a version of the clean, angled geometric bob years before.

All I knew about Sassoon was the jingle for his commercial: "If you don't look good, we don't look good."

But Sassoon, who died at 84 on Wednesday in Los Angeles after suffering from leukemia, was responsible for more than creating the geometric haircut first made famous in the 1960s by mod girl Mary Quant. He would revolutionize the hair-care industry, upgrading hairstyling from a trade into a profession and beauty shops to salons.

"He was my hair hero," said Kevin Gatto, owner of Verde Salon in Collingswood. "He's left such an impact on hair and the hair industry, and it has and will be felt for generations."

Before Sassoon, women's hairstyles were created with hot rollers, hair products, and dryers.

"People dressed the hair," said Alan Gold, a Bala Cynwyd-based hairstylist who attended Sassoon classes in California during the 1980s. Sassoon created the concept of using "architectural principles," which required little styling and allowed the hair to fall into place perfectly every time.

That 1960s bob established a look of the decade, but his styles also included the five-point cut and the "Greek Goddess," a short, tousled perm — inspired by the "Afro-marvelous-looking women" he said he saw in New York's Harlem.

For regular women, he freed them from the shackles of heavy-handed styling — essentially inventing wash-and-wear, a nice fit with the fledgling women's liberation movement.

"His work changed the entire dynamics on how a woman looked at her hair," Gold said "It completed her outfit. Hair stopped being an adornment, and it became an accessory, like a great pair of boots or the length of a skirt. His look made women current and separated the generations."

He made the haircutting experience glamorous, not unlike Sassoon himself. With his good looks and black-rimmed glasses, he was the first hairstylist almost as popular as the celebrities he styled.

Sassoon opened his first salon in his native London in 1954 but said he didn't perfect his cut-is-everything approach until the mid-'60s. Once his concept hit, though, it hit big and many women retired their curlers for good.

His shaped cuts were an integral part of the "look" of Quant, the superstar British fashion designer who popularized the miniskirt, and he was responsible for creating Mia Farrow's pixie, at a reputed cost of $5,000, in the 1968 film Rosemary's Baby.

Sassoon opened more salons in England and expanded to the United States before also developing a line of shampoos and styling products bearing his name. The hairdresser also established Vidal Sassoon Academies to teach aspiring stylists how to envision haircuts based on a client's bone structure. Sassoon hair cutters were considered at the top of their profession, and in 2006 there were academies in England, the United States, and Canada, with additional locations planned in Germany and China.

Sassoon's hair-care mantra: "To sculpt a head of hair with scissors is an art form. It's in pursuit of art."

He wrote four books: Vidal: The Autobiography, released in February; an earlier autobiography, Sorry I Kept You Waiting, Madam, published in 1968; A Year of Beauty and Health, written with his second wife, Beverly, and published in 1979; and 1984's Cutting Hair the Vidal Sassoon Way.

He sold his business interests in the early 1980s to devote himself to philanthropy. The Boys Clubs of America and the Performing Arts Council of the Music Center of Los Angeles were among the causes he supported through his Vidal Sassoon Foundation. He later became active in post-Hurricane Katrina charities in New Orleans.

A veteran of Israel's 1948 War of Independence, Sassoon also had a lifelong commitment to eradicating anti-Semitism. In 1982, he established the Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of anti-Semitism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Growing up very poor in London, Sassoon said that when he was 14, his mother declared he was to become a hairdresser. After traveling to Palestine and serving in the Israeli war, he returned home to fulfill her dream.

"I thought I'd be a soccer player but my mother said I should be a hairdresser, and, as often happens, the mother got her way," he told the Associated Press in 2007.

He told the Chicago Tribune in 2004 that he was proud to have entered the field.

"Hairdressers are a wonderful breed," he said. "You work one-on-one with another human being and the object is to make them feel so much better and to look at themselves with a twinkle in their eye."

Married four times, Sassoon had four children with his second wife, a sometime film and television actress usually billed as Beverly Adams.

Contact Elizabeth Wellington at 215-854-2704 or ewellington@phillynews.com, or follow on Twitter @ewellingtonphl. Read her blog, "Mirror Image," at philly.com/mirrorimage.

This article contains information from the Associated Press.