Mirror, Mirror: Fighting 'fast fashion': Consumers must insist on safe style

If nothing else, so-called fast fashion is cute. A Michael Kors-esque striped maxi skirt for $25 at Zara? I can always rationalize that purchase, right?

If nothing else, so-called fast fashion is cute. A Michael Kors-esque striped maxi skirt for $25 at Zara? I can always rationalize that purchase, right?

Not really.

Fast fashion may keep us on trend within a small budget, but it has done considerable damage to our local and national economy by stuffing our closets with subpar clothing made by workers paid the lowest wages.

At its worst, fast fashion is actually killing people.

In the last year, several deadly accidents - including one fire that killed 112 people - have taken place at manufacturing facilities in Bangladesh, the second-largest exporter of clothing in the world and one of the world's poorest nations. This month, eight people died in a fire at a sweater plant there.

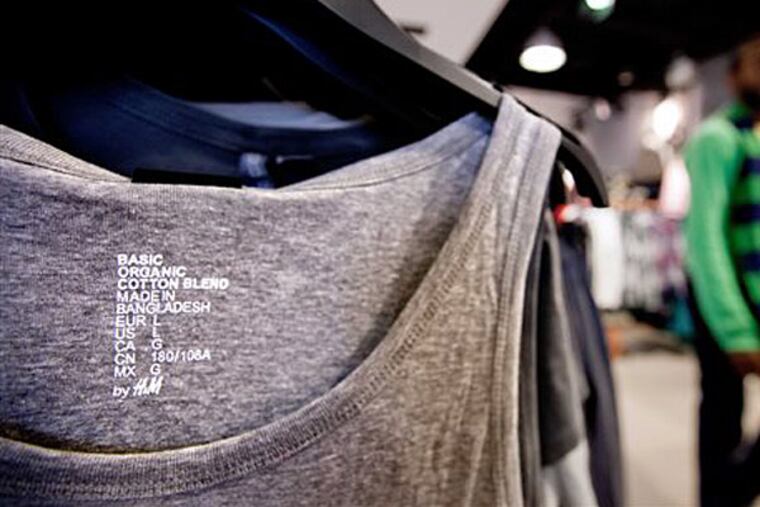

The most horrific was the April 24 collapse of the eight-story Rana Plaza complex in the city of Savar, which housed five factories. The disaster killed more than 1,100 workers, mostly women, who were buried in rubble while assembling the latest looks destined for the racks of Gap, H&M, Zara, and other specialty and big-box stores.

It has been widely reported that the $20 billion garment industry is rife with corruption; factory owners seemingly would rather risk the lives of employees than ensure safe workplaces.

"We don't ever really think about how what we wear affects people's lives on a global scale," said Sarah Van Aken, owner of the Philadelphia-based wearable women's wear brand SA VA.

From 2006 to 2009, Van Aken manufactured her collections at a small factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh. There she paid workers more than 15,000 takas, about $200, a month. Most factory workers make about 3,000 takas, or $38, a month.

"When I heard about the collapse, I was heartbroken," Van Aken said, sitting behind a glass desk at her new sewing facility in Kensington. "It's really tough because people are so poor there. And the answer isn't just pulling out. . . . In some cases, the child or the woman that works in that factory is the only breadwinner in their family."

She described Bangladesh with people living in tin-roofed homes and children begging in the streets. Manufacturing facilities are fashioned from bamboo, and massive piles of fabrics sit on facility floors, an obvious fire hazard. The complexes are like fortresses. Fire escapes are bolted shut, which keeps the clothes from getting out to the black market.

In the weeks since the latest disasters, there has been a lot of talk about what Western-based companies, many with billions in annual sales, can do to improve working conditions for Bangladesh's 3.6 million garment workers.

When Walmart discovered that some of its private-label brands outsource manufacturing to Bangladesh, Walmart dropped those companies.

Brands including H&M, Mango, and the parent companies of Zara and Calvin Klein are negotiating contracts with Bangladesh factories promising to conduct independent safety inspections. Gap officials say they intend to sign such an agreement, but haven't yet because of liability issues.

What really would make an impact is mindful shopping. After all, if there is no demand, supply would end, too. We like to shop. But we must insist that our favorite fashion brands, both fast and luxury, work harder to secure the safety of their overseas workers.

We also should be willing to spend more money on apparel made Stateside.

Slowly, these things are happening.

I've been chronicling the shift in my column by spotlighting designers like Van Aken, who manufacture in America.

Van Aken stopped manufacturing in Bangladesh because "the cost of doing business far outweighed the savings." In 2009, she opened a facility on Sansom Street where she cut, sewed, and sold her collection.

Six weeks ago, after raising nearly half a million dollars through a capital campaign, Van Aken opened a facility in Kensington, where she cuts and sews all of her samples. She has the rest of her collections made in facilities in North Philadelphia. Her store remains on Sansom Street.

"I had outgrown my business, but I still wanted to stay local," Van Aken said. "That's very important to me. It's very important to our community."

Luckily for me, she's selling maxi skirts, both solid and striped, this season.